Reference: July-August 2025 | Issue 4 | Vol 18 | Page 12

Start this Module

Module Title

Managing T2DM in primary careModule Author

Theresa Lowry LehnenCPD points

2Module Type

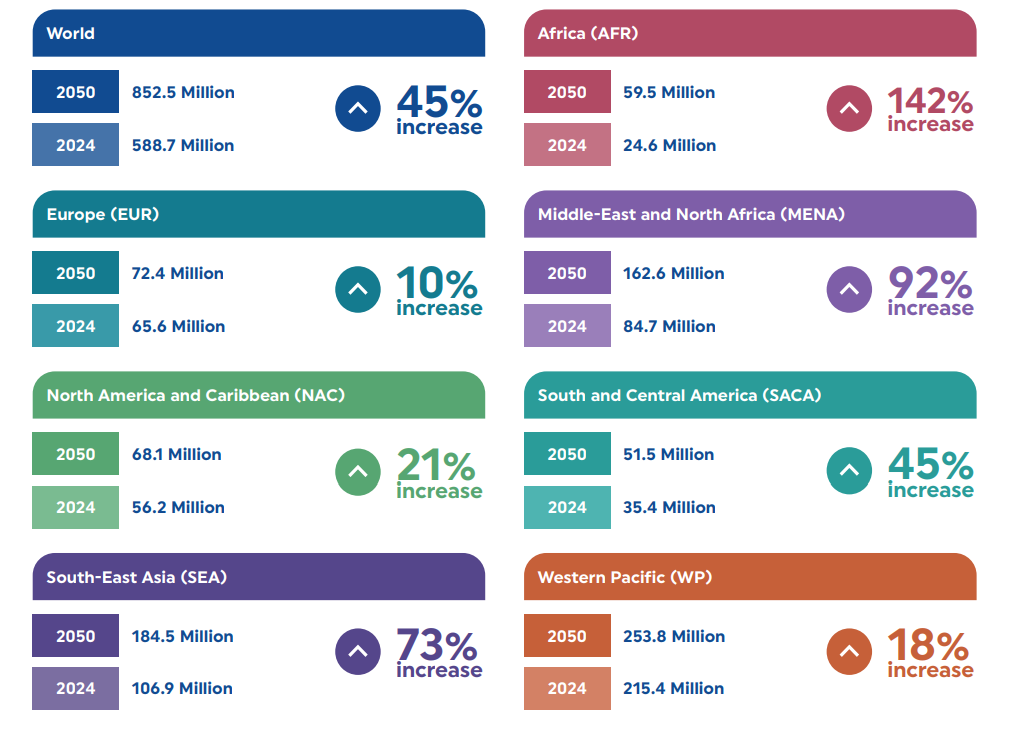

TutorialDiabetes is a major global health issue, affecting one in nine adults worldwide and accounting for around 12 per cent of global health expenditure.1 Recognised as a lifelong metabolic condition, diabetes was listed by the World Health Organisation (WHO) as one of the top 10 leading causes of death globally in 2019.2 Future projections are alarming, and the incidence of disease is expected to rise sharply.

This CPD module details the rising prevalence of type 2 diabetes (T2DM) based on the latest global figures, and outlines the primary considerations for managing the disease in Ireland, with a particular focus on the role of the nurse in general practice. However, the information contained in the module is suitable for nurses from all backgrounds and specialties, who will undoubtedly encounter patients with the disease.

The risk factors, signs and symptoms, diagnosis, and complications of T2DM are addressed, as is the treatment and management of the condition – both pharmacological and non-pharmacological. The current model of care for T2DM in Ireland, including inequalities and barriers to optimal treatment, are also described to guide the nurse through the current care pathways available for patients nationally.

Rising prevalence

The International Diabetes Federation (IDF) released updated figures in 2025 showing that 589 million adults aged 20-79 years are currently living with diabetes, a significant increase from previous estimates.1 Four in 10 adults globally, and one in three adults in Europe, are now estimated to live with undiagnosed disease, the majority of which is T2DM.

In 2024, diabetes and its related complications were estimated to be responsible for the deaths of approximately 3.4 million adults aged 20-79 worldwide. This figure includes 2.4 million deaths among individuals with diagnosed diabetes and an additional one million among those who are undiagnosed.1

Overall, these deaths accounted for 9.3 per cent of all global mortality within this age group – a notably significant figure.1 The global prevalence of diabetes is projected to rise to 643 million by 2030, 784 million by 2045, and 853 million by 2050.

In 2024, more than 9.5 million individuals were living with type 1 diabetes globally, including approximately 1.9 million children and adolescents under the age of 20. T2DM accounts for over 90 per cent of all diabetes cases and is influenced by a complex interplay of socioeconomic, demographic, environmental, and genetic factors.

Major drivers behind the growing prevalence of T2DM include urbanisation, population ageing, declining physical activity levels, and the rising rates of overweight and obesity.¹

Due to the current absence of a national diabetes registry in Ireland, the exact number of individuals living with diabetes remains uncertain. Diabetes Ireland suggest that approximately 266,664 people are affected by the condition nationally.3 However, the HSE is currently assembling a dedicated team to establish Ireland’s first national diabetes registry, a landmark initiative that will also serve as the HSE’s inaugural chronic disease data system.

After years of advocacy, Diabetes Ireland has expressed strong support for the announcement of a national diabetes registry. The charity described the initiative as a significant milestone, stating that it is “long overdue”, and has the potential to revolutionise diabetes care by delivering vital data to enhance patient outcomes and inform healthcare service planning.3

As Ireland’s population ages and obesity rates rise, the incidence of T2DM continues to grow nationally as well as globally. With increasing prevalence, earlier onset, and a complex interplay of comorbidities, the management of T2DM demands a structured and integrated approach.

General practice is the cornerstone of diabetes care in Ireland, and the roles of the general practice nurse (GPN) and general practice advanced nurse practitioner (GPANP) have become increasingly pivotal in delivering structured, proactive, and preventative care under the HSE’s Chronic Disease Management (CDM) Programme.4

Pathophysiology

T2DM is a progressive metabolic disorder characterised by hyperglycaemia resulting from insulin resistance and beta-cell dysfunction.3 It develops insidiously over many years, typically beginning with insulin resistance, a state in which peripheral tissues such as muscle, adipose, and liver cells fail to respond adequately to circulating insulin.

This resistance impairs glucose uptake by cells and promotes hepatic gluconeogenesis, resulting in elevated fasting glucose levels. Over time, pancreatic beta-cells attempt to compensate by increasing insulin production. However, chronic metabolic stress and glucotoxicity lead to progressive beta-cell dysfunction and apoptosis. This culminates in relative insulin deficiency and persistent hyperglycaemia.

The disease is also associated with chronic low-grade systemic inflammation, oxidative stress, and lipid abnormalities, all of which contribute to endothelial dysfunction and the development of microvascular and macrovascular complications, including retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy, coronary artery disease, and stroke.5,6

Risk factors

T2DM develops due to a complex interaction between genetic susceptibility and modifiable risk factors, many of which are closely tied to lifestyle behaviours and broader social determinants of health.

While a genetic predisposition can increase an individual’s likelihood of developing the condition, the current global rise in T2DM prevalence is primarily driven by environmental and behavioural changes. Rapid urbanisation has led to more sedentary lifestyles, greater reliance on processed and calorie-dense foods, and reduced opportunities for physical activity – all of which contribute to weight gain and insulin resistance.1,5,6

Ageing populations also play a significant role as the risk of developing T2DM increases with age due to factors such as reduced beta-cell function and increased insulin resistance over time. Overweight and obesity, particularly central obesity, are major risk factors for T2DM, as excess adipose tissue interferes with glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity.

Increased visceral adiposity releases pro-inflammatory cytokines (eg, tumour necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-6) that impair insulin signalling. Lifestyle changes to achieve a 10 per cent weight reduction can improve glycaemic control and reduce complications.1,5,6

Individuals with a family history of diabetes are at increased risk, suggesting a hereditary component to the disease. Women who have had gestational diabetes are also more likely to develop T2DM later in life.

Ethnic background further influences risk, with higher prevalence observed among South Asian, African-Caribbean, and Hispanic populations due to both genetic factors and disparities in access to healthcare, health literacy, and socio-economic status.

Social determinants such as income, education, housing, and access to healthy food and recreational spaces shape lifestyle behaviours and healthcare access, making them key contributors to the global diabetes burden. Understanding and addressing these multifactorial influences is important for effective prevention, early detection, and long-term management of T2DM.1 5,6

Symptoms, history, and assessment

Patients with diabetes mellitus commonly present with a range of symptoms, the most frequent of which include polydipsia, polyuria, persistent fatigue, and reduced energy levels. Recurrent bacterial or fungal infections, particularly of the skin and genitourinary tract, are also typical, along with delayed wound healing.

Some individuals may report sensory disturbances such as numbness, tingling, or burning sensations in the hands and feet, suggestive of peripheral neuropathy, while others may experience visual disturbances, including blurred vision, due to hyperglycaemia-induced changes in the lens of the eye.6

In the early stages, patients may exhibit mild to moderate hyperglycaemia, which can progress to more severe metabolic disturbances if left untreated. Stressful events or infections can precipitate acute complications, such as marked hyperglycaemia or diabetic ketoacidosis.6

A thorough medical history, physical examination, and investigative tests are required to form a diagnosis for T2DM. The patient’s history will include an assessment for risk factors such as a family history of diabetes, ethnicity, and increased age >40 years old.

A comprehensive clinical assessment is important. This includes recording measurements such as height, weight, and body mass index (BMI), which are important for evaluating metabolic risk. Screening for diabetic complications is also important. An ophthalmologic evaluation should be conducted to assess for diabetic retinopathy.

Vascular examination involves palpation of peripheral pulses to detect signs of peripheral arterial disease. Both history-taking and physical examination are required to assess for peripheral and autonomic neuropathy, ensuring early identification and management of diabetes-related complications.6

Diagnosis

T2DM is typically diagnosed using a combination of blood tests, including haemoglobin (Hb)A1c and fasting blood glucose levels, and/or the oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT).7 The HbA1c test measures average blood sugar levels over the past two to three months, providing a snapshot of glucose control.8,9 Fasting blood glucose measures blood sugar levels after an overnight fast, providing an indication of how the body processes glucose.7

The OGTT involves fasting overnight, followed by a baseline blood sugar measurement. After this, a glucose solution is consumed and blood sugar levels are measured at specific intervals, usually at one hour and two hours post-consumption, to assess how the body processes glucose.

The test is commonly used to diagnose conditions such as pre-diabetes and gestational diabetes.7 HbA1c is widely used in general practice for both diagnosis and ongoing monitoring, provided there are no factors that affect red cell turnover or haemoglobin variants.7

There are patient groups in whom HbA1c is inappropriate for diagnosis, including children and pregnant women; people who are taking medicines such as steroids or antipsychotics that can cause an acute blood glucose increase; individuals with acute pancreatic damage or with haematological conditions that may influence HbA1c and its measurement, eg, haemoglobinopathies, decreased erythropoiesis/administration of erythropoietin, erythrocyte destruction, alcoholism, chronic kidney disease, and chronic opioid use.8

Diabetes is confirmed when one of the following criteria is met: A fasting plasma glucose level of ≥7.0mmol/L, a HbA1c level of ≥48mmol/mol (6.5%), or a two-hour plasma glucose level of ≥11.1mmol/L following a 75g OGTT. Any of these findings must be confirmed either by repeating the same test on a different day or by using a different diagnostic method on the same day. Additionally, a diagnosis can be made without further confirmation if a patient presents with classic symptoms of hyperglycaemia and a random plasma glucose level of ≥11.1mmol/L.10

Complications

People living with T2DM face significantly elevated risks of several serious health complications, most notably cardiovascular and neurological conditions. The IDF Diabetes Atlas (2025) indicates that individuals with T2DM have a 72 per cent increased risk of experiencing a heart attack, a 52 per cent higher likelihood of stroke, and an 84 per cent greater risk of developing heart failure compared to those without diabetes. These increased risks are largely due to the chronic effects of hyperglycaemia, insulin resistance, and associated metabolic disturbances that damage blood vessels and impair cardiac function.1

In addition to cardiovascular disease, T2DM is linked to a 56 per cent higher risk of developing dementia, including both Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. The risk of cognitive decline is particularly pronounced in individuals diagnosed with diabetes at a younger age, suggesting a cumulative impact of prolonged metabolic dysfunction on brain health. This highlights the importance of early intervention and sustained glycaemic control to mitigate long-term neurocognitive effects.1

Ocular complications are also common. Approximately one in four adults with diabetes develop some degree of diabetic retinopathy, a progressive condition caused by damage to the blood vessels in the retina.

Without regular screening and timely treatment, retinopathy can lead to vision impairment or blindness. These findings emphasise the systemic nature of T2DM and highlight the importance of comprehensive, multidisciplinary management to address both glycaemic control and the broader spectrum of associated health risks.1

Model of care for T2DM in Ireland

The HSE model of care for T2DM in Ireland sets out how health services should be structured and delivered for people living with the disease. It outlines the types of services required, identifies the appropriate professionals to provide them, and specifies where care should take place – applying a whole-system approach across primary, secondary, and tertiary care.10 The HSE’s integrated model of care for T2DM outlines four levels of care based on patient need:

- Level 0 supports self-management through education and lifestyle advice.

- Level 1 involves routine management in general practice for stable cases under the CDM programme.

- Level 2 offers short-term specialist input from community-based diabetes teams for more complex needs.

- Level 3 provides ongoing care in hospital settings for patients with unstable or advanced diabetes.

This system ensures appropriate, coordinated care at every stage. The tiered approach ensures people with T2DM receive personalised care that is proportionate to the complexity of their condition, while supporting integration across primary, community, and acute services.10

The primary goal is to improve health outcomes, quality of life, and overall wellbeing for those with T2DM. The model emphasises early detection and timely intervention to prevent complications, rather than delaying treatment until issues arise. It promotes a risk-stratified approach, matching the intensity of interventions to the patient’s level of risk to maintain optimal health.10

A person-centred approach is central to diabetes care in primary care settings. It supports each stage of the patient journey, from early screening and appropriate referrals to diagnosis, management, and regular review. Screening for complications, including cardiovascular disease, diabetic kidney disease, and foot or eye conditions, is important.

Care should be tailored to the individual, reflecting their needs, and should be supported by a structured care plan and access to self-management education. Effective communication adapted to the patient’s literacy or communication needs and clear referral pathways to specialist services are also important.10

People with T2DM often require a range of primary care and social services. To support ongoing diabetes management, it is important that patients are enrolled in the CDM programme through their GP, or are under the care of a hospital-based diabetes team, depending on clinical complexity.

Individuals aged 18 or older who hold a medical card or GP visit card are eligible for the CDM programme. It provides two GP-led reviews per year, each preceded by a consultation with a GPN for physical assessment, blood tests, and patient education. These collaborative reviews address lifestyle changes and/or medical management, with a jointly agreed care plan reviewed every six months.3,10

The CDM programme promotes structured, guideline-driven care by reimbursing general practices for scheduled reviews. These include checks of HbA1c, blood pressure, lipids, BMI, smoking status, renal function (glomerular filtration rate and urine albumin to creatinine ratio), and diabetic foot screening.

However, the programme is only freely available to those with a medical or GP visit card, which can lead to unequal access. Non-cardholders aged 18 years and above registered on the CDM prevention programme with a diagnosis of gestational diabetes or pre-eclampsia, and who develop diabetes, are also eligible for registration on the CDM programme.3

Data from TILDA indicate that 31.6 per cent of adults aged 50 and over with self-reported T2DM do not hold either card. As a result, nearly one-third of this group are ineligible for structured care, even though many have uncomplicated diabetes suitable for management in primary care. Financial barriers limit access and highlight the need to extend the programme to all who would benefit from regular diabetes reviews.11

Self-management programmes

Early access to education and resources helps patients manage the practical and psychological demands of a T2DM diagnosis. Information about entitlements, including the Long-Term Illness Scheme and the National Diabetic Retinal Screening Programme, should be clearly provided at an early stage.10

Newly diagnosed patients should be referred to evidence-based diabetes self-management education and support (SMES) programmes within three months of diagnosis. There are four key stages when the need for SMES should be reassessed: At diagnosis; annually or when treatment goals are not being met; when complications arise (whether medical, physical, or psychosocial); and during transitions in care.10

Community-based specialist diabetes care is provided through multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) located in local ambulatory care hubs. These services are free to everyone, based on clinical need, and aim to provide timely access to care and education. The community teams support general practice and serve as a link to hospital-based services.

Their goal is to provide accessible, specialist input for people with complex chronic diseases, including those with co-existing conditions like cardiovascular disease or heart failure. Collaborative care across specialty teams ensures coordinated and effective management in a community setting.10

These education programmes are delivered in both group and individual formats. The HSE offers SMES programmes free of charge to all patients with type 2 diabetes, regardless of medical card status.

Programmes typically include an initial core course with follow-up sessions, and are available both in-person and online to accommodate local needs. Patients are encouraged to bring a support person, such as a family member or carer, to enhance engagement and support. For those unable to participate in group sessions, individual nutrition therapy is available through referral to the community dietitian.10

Specialist services at Level 2 ambulatory care hubs should be used for short-term interventions, such as specialist assessment, education, or clinical optimisation, not for routine care. Coordination between primary care and diabetes specialist teams is encouraged, especially when individuals are also being treated for other conditions.10

Treatment and management of T2DM

The treatment and management of T2DM requires an integrated approach that includes achieving and maintaining glycaemic control, reducing cardiovascular risk, and preventing or detecting complications early. Glycaemic targets are met through a combination of lifestyle changes and pharmacological therapies tailored to the individual. Cardiovascular risk reduction involves managing blood pressure, lipid levels, weight, and encouraging smoking cessation if required.

Routine screening for complications such as retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy, and foot disease is important for timely intervention. Patient empowerment, supported by structured education and self-management programmes, plays an important role in fostering engagement, improving adherence, and enhancing long-term outcomes.

NON-PHARMACOLOGICAL MANAGEMENT

Non-pharmacological management forms the foundation of care and includes dietary intervention, increased physical activity, and behavioural support. Patients with T2DM should be encouraged to eat high fibre, low glycaemic index sources of carbohydrates such as fruit, vegetables, wholegrains, and pulses, as well as low fat dairy products and oily fish. Dietetic referral is recommended, particularly at diagnosis. Patients are encouraged to engage in at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise per week, alongside resistance training.3,10

In Ireland, free structured education programmes are available to support people with T2DM in developing the knowledge and skills needed to manage their condition effectively.

These include DISCOVER (Diabetes Insights and Self-Care Options via Education and Reflection), delivered by HSE dietitians; CODE (Community Orientated Diabetes Education), developed and facilitated by Diabetes Ireland nurses and dietitians; and the DESMOND programme (Diabetes Education and Self-Management for Ongoing and Newly Diagnosed), run by HSE dietitians, diabetes nurses, and other healthcare professionals.

Each programme provides evidence-based education focused on lifestyle modification, self-care, and informed decision-making to promote better health outcomes.3,12,13

Patients should receive education on how to correctly monitor and interpret their blood glucose levels as part of effective diabetes self-management. It is recommended that their glucose meter is checked for accuracy at least every three months and that the device is replaced or upgraded every two years to maintain reliability. Patients are encouraged to record their readings in a glucose monitoring diary and bring it to each diabetes review appointment. This record supports clinical decision-making and helps guide ongoing treatment adjustments based on individual trends and targets.14

PHARMACOLOGICAL MANAGEMENT

Pharmacological treatment for T2DM is tailored to the individual, considering glycaemic targets, the presence of comorbid conditions, risk of complications, and patient preferences and priorities. The overall goal is to optimise glycaemic control while minimising side effects and enhancing quality of life.14

First-line therapy

Metformin remains the cornerstone of first-line pharmacological management for most individuals with T2DM. It is favoured for its proven efficacy in lowering HbA1c, established safety profile, low-risk of hypoglycaemia, and its weight-neutral or modest weight-reducing effect. Metformin also has potential cardiovascular benefits and is generally well tolerated, although gastrointestinal side effects may limit use in some patients.15

For patients who do not achieve glycaemic targets on metformin alone, or in whom metformin is contraindicated or poorly tolerated, additional agents are selected based on individual clinical profiles. These include glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) and sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2i).

GLP-1 RAs (eg, semaglutide, liraglutide) are recommended particularly in patients with established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, obesity, or those needing weight reduction. These agents improve glycaemic control and have demonstrated significant cardiovascular risk reduction. They are administered subcutaneously and promote satiety, leading to weight loss.

Once-weekly formulations enhance treatment adherence and are generally more cost-efficient. Although access through the Primary Care Reimbursement Service has improved, long-term availability remains somewhat restricted.15

SGLT2i (eg, empagliflozin, dapagliflozin) are increasingly used, especially in individuals with heart failure or chronic kidney disease, regardless of glycaemic status. By blocking glucose reabsorption in the proximal renal tubules, SGLT2i promote glycosuria and glucose lowering.

These agents have been shown to reduce the risk of heart failure, hospitalisation, and slow progression of renal disease. However, their effectiveness diminishes as kidney function declines, and they may increase the risk of genitourinary infections. Several SGLT2i are now available via the Primary Care Reimbursement Service, improving access in the Irish healthcare system.15

Other commonly prescribed agents include:

- Sulphonylureas (eg, gliclazide) may still be used, particularly where cost or access is a concern. However, they are associated with a higher risk of hypoglycaemia and weight gain, and are now generally considered second-line, especially in older adults or those at high risk of cardiovascular events.15

- Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors (eg, sitagliptin) offer modest glucose-lowering efficacy, are weight-neutral, and have a low-risk of hypoglycaemia. They may be considered when GLP-1 RAs or SGLT2i are not suitable.14

Insulin therapy

Insulin may be required for some patients with T2DM, particularly when oral therapies are insufficient. Initiation of insulin is considered for patients with severe hyperglycaemia (eg, HbA1c >85mmol/mol or fasting glucose >15mmol/L), significant symptoms, or in whom oral and non-insulin injectable agents fail to achieve target control.

Basal insulin is typically initiated first, with titration as needed. Insulin may also be necessary in situations of acute illness, surgery, or pregnancy, and it is important that blood glucose levels are closely monitored during these periods.15

Consideration of patient lifestyle, concerns, treatment goals, and capacity to manage injectable therapies is important. Ongoing review and adjustment of medication regimens are required to ensure continued appropriateness and effectiveness.14

The aim of glycaemic control is to reduce the risk of complications without inducing hypoglycaemia. HbA1c targets should be individualised, generally <53mmol/mol (7%), with more relaxed targets in older adults or those with comorbidities. Blood pressure control and lipid management are important,6,7 and the annual cycle of care review as part of the CDM programme ensures that all aspects of care are addressed systematically.

The GPN and GPANP play particularly important roles in delivering many components of this holistic care, collaborating with other members of the MDT, and supporting patients with decision-making and disease management.

Diabetic foot model of care

GPNs conduct structured assessments, including foot screening using monofilament testing, pulse palpation, and visual inspection for skin integrity, deformities, and other risk factors,14 and hence, play a central role in diabetic foot care.

The HSE’s Diabetic Foot Model of Care (2021) outlines a structured approach to diabetic foot screening and risk assessment for individuals with T2DM. The primary goal is to identify each person’s risk of developing diabetic foot ulcers. All individuals with diabetes are assigned a risk category and, if needed, referred for further foot screening, assessment, and a tailored care plan. This ensures patients receive annual or more frequent foot checks, education on foot care, and reviews aligned with their clinical risk and delivered in the most appropriate setting.16

An exception is made for individuals with highly complex T2DM, who should receive annual foot care directly from their endocrinology team.16 Based on screening results, individuals are classified into one of several categories: Low, moderate, or high risk of developing foot ulcers; in remission if they have a history of ulceration; or active foot disease if an ulcer is present or Charcot foot is suspected.16

Complications and comorbidity management

As discussed, T2DM is associated with significant microvascular complications (retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy) and macrovascular disease (ischaemic heart disease, stroke, peripheral arterial disease). Early detection and management of complications is vital. All patients should undergo annual retinal screening through the Diabetic RetinaScreen programme and receive regular renal function testing to detect early nephropathy.

Diabetic foot complications, a major cause of morbidity, necessitate regular podiatric assessment and early referral where indicated. Multidisciplinary collaboration, involving dietitians, pharmacists, podiatrists, and secondary care diabetes services, is important to optimise outcomes and the nurse in a central collaborator within the MDT. 10,14, 15

Role of the GPN

The management of T2DM in Ireland is based on a structured, integrated, and person-centred approach, with GPNs and GPANPs playing a central role in its delivery. Under the CDM programme, nurses in general practice are instrumental in providing high-quality, proactive care.

Their key responsibilities include supporting early diagnosis, promoting lifestyle modifications, initiating and monitoring pharmacotherapy, and empowering patients through education and self-management support. Through regular reviews, risk factor management, and collaborative care planning, GPNs and GPANPs contribute significantly to improved outcomes and enhanced quality of life for individuals living with T2DM. Ongoing professional development, interprofessional collaboration, and sustained investment in primary care are essential to support this vital role.10,14

Conclusion

T2DM represents one of the most pressing global health challenges of our time, with prevalence escalating at an alarming rate and projections indicating a continued upward trend well into the coming decades. Its impact is far-reaching, not only due to its high morbidity and mortality but also because of its complex interplay with a range of socioeconomic, behavioural, and environmental factors. In Ireland, the increasing incidence of T2DM, compounded by an ageing population and rising obesity rates, highlights the urgent need for a robust, equitable, and integrated approach to prevention and care.

Early detection, timely intervention, and person-centred, multidisciplinary management are essential to reducing the burden of diabetes and its complications. The HSE’s tiered model of care and the CDM programme provide a strong foundation for structured primary care-based services.

However, gaps in access, particularly for those without medical or GP visit cards, highlight ongoing health inequalities that must be addressed to ensure that all individuals with diabetes receive consistent, evidence-based care.

The role of GPNs and GPANPs in delivering proactive diabetes care, alongside community-based specialist teams, is pivotal in supporting patients through education, regular monitoring, and lifestyle modification. Empowering patients through structured self-management education and support not only improves glycaemic control but also enhances quality of life and reduces long-term complications.

Tackling the diabetes epidemic requires a sustained, coordinated effort across healthcare sectors and communities. Investing in early intervention, accessible care, and health equity are key to improving outcomes, and alleviating the growing societal and economic burden of T2DM.

References

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas. 11th Edition. Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes Federation; 2025. Available at: https://diabetesatlas.org/.

- World Health Organisation. Classification of diabetes mellitus. Geneva: WHO; 2019. Available at: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/hanle/10665/325182/

9789241515702-eng.pdf. - Diabetes Ireland. Diabetes prevalence in Ireland. Dublin: Diabetes Ireland; 2025. Available at: www.diabetes.ie/about-us/diabetes-in-ireland/.

- Health Service Executive. Chronic disease treatment programme. Dublin: HSE; 2025. Available at: www.hse.ie/eng/services/list/2/primarycare/chronic-disease-management-programme/chronic-disease-treatment-programme.html.

- Galicia-Garcia U, Benito-Vicente A, Jebari S, et al. Pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(17):6275.

- Goyal R, Singhal M, Jialal I. Type 2 Diabetes. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- Health Service Executive. Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Getting diagnosed. Dublin: HSE; 2024. Available at: www2.hse.ie/conditions/type-2-diabetes/about/getting-diagnosed/.

- Lam M. Diagnosis and management of type 2 diabetes mellitus. The Pharmaceutical Journal. 2022;303(7929).

- Health Service Executive. HbA1c Testing. Dublin: HSE; 2024. Available at: www2.hse.ie/conditions/type-2-diabetes/managing-blood-glucose-levels/hba1c-testing/.

- Health Service Executive. Integrated Model of Care for People with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Dublin: HSE; 2024. Available at: www.hse.ie/eng/about/who/cspd/ncps/diabetes/moc/hse-integrated-model-of-care-for-people-with-type-2-diabetes-mellitus.pdf

- O’Neill K, McHugh S, Kearney P. Cycle of Care for people with diabetes: an equitable initiative? HRB Open Res. 2019; 2:3. doi:10.12688/hrbopenres.12890.1. Available at: https://hrbopenresearch.org/articles/2-3?utm_source=chatgpt.com

- Health Service Executive. (2024). Diabetes support courses. HSE, Dublin. Available at: www2.hse.ie/conditions/type-2-diabetes/courses-and-support/diabetes-support-courses/#:~:text=CODE%20stands%20for%20Community%20Orientated,It%20is%20available%20online.

- Diabetes Ireland. CODE – Community Orientated Diabetes Education. Available at: www.diabetes.ie.

- Irish College of General Practitioners (ICGP). A Practical Guide to Integrated Type 2 Diabetes Care. Dublin: ICGP and HSE; 2016. Available at: www.hse.ie/eng/services/list/2/primarycare/east-coast-diabetes-service/management-of-type-2-diabetes/diabetes-and-pregnancy/icgp-guide-to-integrated-type-2.pdf.

- O’Keefe D, McVicker L. Understanding diabetes: Type 1 vs Type 2 diagnosis and treatment. Irish Pharmacy News. 2025;15(5):74-76.

- Health Service Executive. Diabetic foot model of care. Dublin: HSE; 2021. Available at: www.hse.ie/eng/about/who/cspd/ncps/diabetes/moc/diabetic-foot-model-of-care-2021.pdf.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.