Reference: September-October 2025 | Issue 5 | Vol 18 | Page 12

Start this Module

Module Title

Crohn’s Disease: Clinical presentation, diagnosis, treatment, and managementModule Author

Theresa Lowry LehnenCPD points

2Module Type

TutorialDespite significant advances in therapeutic options, there remains no definitive cure for Crohn’s

disease, and many patients face persistent symptoms, complications, and eventual need for surgery

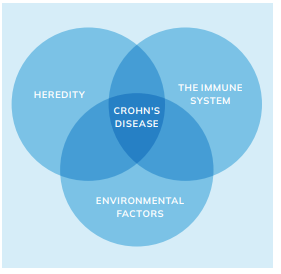

Crohn’s disease is a chronic idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) characterised by transmural inflammation and lesions that can affect the entire gastrointestinal tract, but most commonly occur at the terminal ileum and colon.1 The prevalence of Crohn’s disease has an incidence of three to 20 cases per 100,000. The exact pathogenesis of Crohn’s disease is unknown, although genetic, immune system, and environmental factors have been shown to increase the risk of the illness and lead to the aberrant gut immune response characteristic of the disease.1,2,3

There is strong evidence supporting a genetic predisposition, with at least 32 specific genetic variants identified as being more prevalent among individuals with Crohn’s disease compared to the general population. The familial clustering of the disease provides additional indirect evidence of a hereditary component. Immune system disruption is also central to its pathogenesis. In Crohn’s disease, the immune system overproduces tumour necrosis factor (TNF), a cytokine that attacks all bacteria indiscriminately, including beneficial microbes, leading to chronic intestinal inflammation.1,4

Crohn’s disease most commonly presents between the ages of 15 and 35, though it can develop at any age. The onset of IBD generally follows a bimodal distribution, with incidence peaks occurring in early adulthood (15-35 years) and again later in life, typically between 50 and 60 years of age. It affects men and women equally and is more frequently observed in developed countries and among individuals of Ashkenazi Jewish descent.1

Among environmental risk factors, smoking is the most significant. Smokers are twice as likely to develop Crohn’s disease and tend to experience more severe symptoms than non-smokers.2,3

While diet does not cause Crohn’s disease, certain foods such as dairy, alcohol, spicy, fatty, or high-fibre items can exacerbate symptoms. As a result, dietary management should be tailored to individual tolerance. Stressful life events may coincide with disease flares, but current evidence does not support stress as a causal factor in the development or progression of Crohn’s disease.1,2,4

There are three main phenotypes of Crohn’s disease: Inflammatory, stricturing, and penetrating. Presenting symptoms are variable and some patients may have symptoms for years before the diagnosis of Crohn’s disease is made. Patients with inflammatory disease often present with abdominal pain and diarrhoea, and may develop more systemic symptoms including weight loss, low-grade fevers, and fatigue.

Patients with stricturing disease may develop bowel obstructions while those with penetrating Crohn’s disease can develop fistula or abscesses. When an abscess is present, in addition to abdominal pain, patients can have systemic symptoms such as fever and chills and may also present with signs of acute peritonitis.1,4

Crohn’s disease can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract, with clinical presentations varying widely among patients. The terminal ileum and colon are frequently involved, although disease localisation may be limited to the small bowel or colon in a significant number of cases.

Extraintestinal manifestations (EIMs) are common, affecting approximately 46 per cent of individuals with Crohn’s disease. These include rheumatologic, mucocutaneous, ocular, and hepatobiliary complications. Among these, arthritis is the most prevalent EIM, occurring in up to 25 per cent of patients, highlighting the systemic nature of the disease and the need for multidisciplinary care.5

Clinical presentation

Symptoms of IBD vary depending on which part of the intestine is affected and severity of the disease. Crohn’s disease commonly presents with persistent diarrhoea, abdominal pain, particularly in the lower right quadrant, unintended weight loss, and fatigue. Symptoms often develop gradually and may be accompanied by low-grade fever and reduced appetite.

Depending on the site of inflammation, patients may also report bloating, nausea, or rectal bleeding. EIMs such as joint pain, skin rashes (eg, erythema nodosum), and eye inflammation can occur. In children and adolescents, delayed growth or puberty may be an early sign. The disease is typically chronic and relapsing, with symptom flares followed by periods of remission.1,3,5

| CROHN’S DISEASE | ULCERATIVE COLITIS |

|---|---|

| Inflammation may develop anywhere in the GI tract from the mouth to the anus | Limited to the large intestine (colon and rectum) |

| Most commonly occurs at the end of the small intestine | Occurs in the rectum and colon, involving a part or the entire colon |

| May appear in patches | Appears in a continuous pattern |

| May extend through entire thickness of bowel wall | Inflammation occurs in innermost lining of the intestine |

| About 67% of people in remission will have at least one relapse over the next five years | About 30% of people in remission will experience a relapse in the next year |

TABLE 1: Differences in Crohn’s disease versus ulcerative colitis

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of Crohn’s disease can be difficult given that presenting symptoms can be insidious and nonspecific. Symptoms that require further investigation include weight loss, bloody diarrhoea, iron deficiency, and night-time awakenings. Similarly, significant family history of IBD, unexplained elevations in the C-reactive protein (CRP) level, sedimentation rates, or other acute phase reactants such as ferritin and platelets, or low B12 should prompt further investigation.

There is no single test that can be used to confirm or disprove a diagnosis of Crohn’s disease. The diagnosis of Crohn’s disease is made based on symptoms, endoscopic and radiologic findings (colonoscopy, biopsy, small bowel enteroclysis, CT, MRI, wireless capsule endoscopy). Pathology can also be confirmatory.6,7

Other conditions can mimic the symptoms of Crohn’s disease, so it is important to rule out infection and other causes even when patients with known Crohn’s disease are having flare-ups. Patients with diarrhoea should be assessed for infection, IBD, and, in certain cases, Coeliac disease.

Other conditions that may present like Crohn’s disease include appendicitis, Behçet’s disease, and ulcerative colitis (UC). Both Crohn’s disease and UC are IBDs, but there are some key differences, as outlined in Table 1.6,7

It is important not to confuse an IBD like Crohn’s disease or UC with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). IBS is a disorder that affects the muscle contractions of the bowel and is not characterised by intestinal inflammation, nor is it a chronic disease.1,5

Treatment and management

While there are several medications available to treat Crohn’s disease, there is no cure. The management of Crohn’s disease has, however, evolved significantly, with updated guidelines and therapeutic strategies enhancing patient outcomes.6,7,8

Corticosteroids (locally acting rather than systemic) remain a cornerstone for inducing remission in active mild-moderate Crohn’s disease but are not recommended for maintenance therapy due to potential adverse side effects. Long-term corticosteroid use is discouraged because of risks such as osteoporosis, hypertension, and increased susceptibility to infections.6,7,8,9

Among corticosteroids, budesonide is often the first-line option for patients with mild-moderate ileocecal Crohn’s disease. Budesonide is a locally acting corticosteroid with high first-pass hepatic metabolism, which results in lower systemic bioavailability and a more favourable side effect profile compared to traditional systemic corticosteroids.

This makes it particularly suitable for targeting inflammation confined to the terminal ileum and right colon, while reducing the risk of systemic complications such as adrenal suppression, weight gain, and mood disturbances.6,7,9

Prednisone, a more potent systemic corticosteroid, is typically reserved for patients with more extensive disease, severe flare-ups, or when disease involvement extends beyond the reach of budesonide. While effective in inducing remission, prednisone is associated with a wide range of potential side effects, especially when used for prolonged periods.

These include osteoporosis, hypertension, hyperglycaemia, fluid retention, cataracts, mood changes, and increased susceptibility to infections. There is also concern over the risk of iatrogenic Cushing’s syndrome and adrenal insufficiency following abrupt discontinuation after extended use.6,7,9

Due to these risks, corticosteroids are not recommended for long-term maintenance therapy. Instead, maintenance of remission should be achieved with immunomodulators or biologic agents. All patients on corticosteroids for more than a few weeks should be monitored closely for bone health and may require calcium and vitamin D supplementation or bisphosphonate therapy to reduce the risk of osteoporosis and fractures.9

Current guidelines recommend using corticosteroids for the shortest duration possible, typically aiming for a tapering course over eight-to-12 weeks, and transitioning patients to maintenance therapies early to avoid steroid dependence or resistance. Patients who are steroid-dependent, and those who relapse upon tapering or shortly after discontinuation, should be escalated to steroid-sparing maintenance options.9

Aminosalicylates (5-ASA): According to the 2024 European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO) Guidelines on Therapeutics in Crohn’s Disease, 5-aminosalicylic acid has no role in contemporary management of Crohn’s disease, regardless of disease location, based on a consistent lack of evidence of efficacy.9 So they are not recommended for inducing or maintaining remission in Crohn’s disease, although sulfasalazine may have a role in mild colonic disease.9

Immunomodulators such as azathioprine and mercaptopurine are utilised for maintaining remission in Crohn’s disease. These agents modulate the immune response, reducing inflammation. Regular monitoring of blood counts and liver function is essential due to potential side effects, including leukopaenia and hepatotoxicity. These medications are not effective for inducing remission and are primarily used for maintenance therapy.8,9

The current ECCO guidelines (2024) strongly advise against using thiopurine monotherapy to induce remission in Crohn’s disease, citing very low-quality evidence supporting its effectiveness. However, it also suggests that thiopurine monotherapy may be considered for maintaining remission, although the supporting evidence is of low quality.9

Methotrexate: This drug has fallen out of favour in Crohn’s disease due to the availability of more effective agents. The 2024 ECCO guidelines suggest parenteral methotrexate can be used as induction and maintenance therapy in moderate-severe Crohn’s disease, though noted that studies of oral methotrexate have failed to demonstrate efficacy.

Biologic agents have significantly advanced the management of moderate-severe Crohn’s disease, offering targeted therapies that reduce inflammation and maintain long-term disease remission. Since their widespread adoption, these therapies have improved clinical outcomes, reduced the need for corticosteroids, and decreased hospitalisation and surgical intervention rates.6,7,8

First-line biologic options for Crohn’s disease include infliximab and adalimumab, both anti-TNF agents that inhibit TNF-alpha, a key driver of intestinal inflammation. Ustekinumab, an interleukin-12 (IL-12) and interleukin-23 (IL-23) inhibitor, and vedolizumab, an integrin receptor antagonist that targets gut-specific inflammation, are also widely used based on disease phenotype and patient characteristics. These agents are typically initiated in patients with moderate-severe disease who have not achieved adequate control with conventional therapies such as corticosteroids, immunomodulators, or 5-ASA drugs.6,9,10

Risankizumab, a selective IL-23 inhibitor, represents a newer class of biologics and is approved for use in adults with moderately-severely active Crohn’s disease who have had an inadequate response to, lost response to, or are intolerant of conventional or biologic therapy.

In Ireland, the HSE restricts risankizumab to second-line or subsequent use, meaning it may only be prescribed after failure or intolerance of a lower-cost biologic option, in alignment with cost-effectiveness and reimbursement policies. Clinical trials have shown risankizumab to be effective in inducing and maintaining remission in patients with refractory Crohn’s disease, offering an additional treatment avenue for those with limited therapeutic options.10

Before initiating biologic therapy, it is important to screen for latent infections, including tuberculosis and hepatitis B, to mitigate the risk of reactivation during immunosuppressive treatment.9

Over time, some patients undergoing biologic therapy may experience a diminished treatment effect. This loss is frequently linked to the formation of anti-drug antibodies. Measuring serum trough levels alongside drug-specific antibody concentrations, an approach known as therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM), can help guide management. TDM is now widely used in clinical practice for symptomatic patients on anti-TNF therapy, with multiple studies supporting its effectiveness in improving outcomes when response begins to wane. 11

Biosimilars: Several biosimilars have been approved for use in the treatment of IBD, including those for infliximab, adalimumab, and ustekinumab, which are licensed by the European Medicines Agency (EMA).11

Due to the high cost of biologic therapies, which routinely rank among the top 10 in hospital drug spending in Ireland, the HSE’s Acute Hospital Drug Management Programme introduced a 50 per cent biosimilar uptake target in February 2018 for biologics with an available biosimilar. However, adoption rates remain inconsistent across the country and among hospital groups, with usage ranging from 0 to 100 per cent depending on the facility.11

Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors: Tofacitinib, an oral non-selective JAK inhibitor, is authorised by the EMA for use in patients with moderate-severe UC who have not responded to conventional therapies. More recently, the EMA has also approved additional JAK inhibitors, filgotinib and upadacitinib, for the treatment of UC.11

Upadacitinib is the only JAK inhibitor currently recommended for both induction and maintenance of remission in moderate-severe Crohn’s disease. The 2024 ECCO guidelines provide a strong recommendation for its use in both phases of treatment, supported by high-quality evidence for induction and moderate-quality evidence for maintenance, with full consensus.9

Since 2024, the HSE has approved reimbursement of upadacitinib for the treatment of adult patients with moderately-severely active Crohn’s disease who have had a failed response to either conventional therapy or a biologic agent (ie, TNF-a inhibitor).

Advanced combination therapy may be considered for patients with refractory Crohn’s disease or those with uncontrolled EIMs or immune-mediated conditions requiring more than one agent for remission. However, ECCO guidelines suggest it is not recommended for treatment-naïve patients, including those at high risk, due to a lack of supporting evidence.9

Surgical intervention is indicated in Crohn’s disease when medical management fails to control symptoms or when complications such as strictures, fistulas, abscesses, or perforation occur.1,2 The most common surgical procedure involves resection of the affected bowel segment with primary anastomosis. In cases of severe inflammation or infection, where anastomosis poses a high risk, a temporary diverting stoma (ileostomy or colostomy) may be formed. This allows the bowel to rest and inflammation to subside before re-anastomosis is considered.

Most patients’ post-surgery for medically-refractory UC have an end ileostomy. Patients who choose to undergo ileostomy reversal may proceed with an ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. In some cases, inflammation of the constructed ileal pouch, known as pouchitis, can occur. This condition typically responds effectively to antibiotic therapy or, in certain instances, to anti-TNF treatment. Permanent colostomy may be required if the rectum is removed.1,2,8,11

Approximately 80 per cent of patients with Crohn’s disease will require surgical intervention during their illness. While surgery can induce prolonged remission and improve quality of life, it is not curative. Postoperative recurrence is common, particularly at the site of the anastomosis. Maintenance medical therapy following surgery is important to reduce the risk of recurrence and maintain disease control.1,2,8

In addition to pharmacological and surgical interventions, comprehensive management of Crohn’s disease should include smoking cessation support, correction of nutritional deficiencies, and adherence to preventive care measures. These include up-to-date vaccinations, osteoporosis screening, and sun protection advice, in line with ECCO guideline recommendations.11

Adverse effects of Crohn’s disease therapy

Patients with Crohn’s disease face increased cancer risks, including small bowel adenocarcinoma, colonic cancer, and melanoma. Immunosuppressive treatments, such as thiopurines and biologics, raise the risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer and lymphoma, with the highest lymphoma risk in patients aged 65+. Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma is a rare but serious concern, particularly in young males on thiopurines.8

There is also an elevated risk of serious infections, including pneumonia, shingles, and C. difficile colitis, especially when on corticosteroids or biologics. Routine vaccinations (eg, pneumococcal, shingles) and surveillance are recommended.8

Osteopaenia and osteoporosis are common, particularly with prolonged corticosteroid use; patients with >three months of corticosteroid exposure should undergo bone density screening. Immunosuppressive therapy following cancer is not clearly linked to increased recurrence, but gut-selective agents like vedolizumab may be preferred.8

Assessment and monitoring

Regular specialist follow-up is important in Crohn’s disease to monitor disease progression and screen for colorectal cancer. Many Irish hospitals now offer multidisciplinary IBD clinics with gastroenterologists, IBD nurses, surgeons, dietitians, and psychologists.11

Clinical and biochemical response should be evaluated within 12 weeks, with endoscopic or imaging-based response assessed by six months. Combination therapy patients may consider immunomodulator withdrawal after 18-24 months if in confirmed remission.11

Routine endoscopy is not needed for stable patients. Inflammatory markers (CRP, full blood count, albumin), should be checked biannually, and faecal calprotectin is used during flares as a non-invasive tool. Surveillance colonoscopy is recommended eight-10 years post-diagnosis and every one-five years thereafter, based on risk.11

Renal function should be monitored every three months in patients on aminosalicylates. Those on immunosuppressants need regular blood monitoring, and steroid-treated patients require vitamin D assessment and calcium supplementation. All patients should be referred to an IBD nurse specialist and receive appropriate educational resources.11

Clinical nutrition in IBD

Nutritional management in IBD aims to optimise intake, prevent malnutrition, and avoid symptom-triggering foods. While malnutrition can occur in both UC and Crohn’s disease, it is more common in Crohn’s disease due to its potential to affect any part of the GI tract. Malnutrition may result from reduced intake, increased nutrient loss, and heightened metabolic demands, particularly during active inflammation. Crohn’s disease patients remain at risk even in remission, while nutritional issues in UC usually occur during flares.7,8,11

There is no universal diet to induce remission, but adequate calorie and protein intake is important. Protein needs rise during active disease. Iron supplementation is advised in cases of iron deficiency anaemia – oral iron for mild, inactive cases; and parenteral for active disease. Calcium and vitamin D levels should be monitored and supplemented, especially in steroid-treated patients.7,8,11

Patients with significant diarrhoea or high-output stomas require fluid and electrolyte monitoring. In Crohn’s disease with strictures or obstructive symptoms, a low-fibre, modified-texture diet may help.11

Oral nutritional supplements are used to support intake when needed. If oral intake is inadequate, enteral feeding is preferred. Parenteral nutrition is reserved for cases where enteral routes are not feasible, such as bowel obstruction, short bowel syndrome, anastomotic leaks, or high-output fistulas.7, 8,11

Novel therapies

Despite advances in IBD treatment, many patients do not achieve sustained remission. Ongoing research is expanding understanding of the immune pathways driving gut inflammation, leading to the development of targeted therapies.11

Emerging treatments include agents that modulate leukocyte trafficking, adhesion molecules, sphingosine-1-phosphate receptors, and key cytokines such as TL1A and IL-36. Novel inhibitors targeting JAK and phosphodiesterase pathways are also in development.

JAK inhibitors like upadacitinib and filgotinib have demonstrated improved remission rates. These evolving therapies offer promising alternatives to conventional treatments, with the goal of improving long-term outcomes and achieving remission in a broader range of patients.11

The hidden costs of Crohn’s and colitis in Ireland

In Ireland, the annual incidence rate of Crohn’s disease is estimated at 5.9 per 100,000 people, and 14.9 per 100,000 for ulcerative colitis.11 A 2025 report by Crohn’s and Colitis Ireland, in partnership with Johnson & Johnson Ireland, reveals that 60 per cent of people living with IBD in Ireland face financial hardship due to their condition.12

Irish patients spend an average of €3,264 annually managing the condition, including treatment and dietary costs. Nearly half (47 per cent) report avoiding necessary medical care due to financial constraints, raising concerns about deteriorating health outcomes.12

Beyond direct costs, IBD places a significant indirect financial burden on patients. Time off work and lost income were reported by 62 and 82 per cent of respondents respectively. Travel expenses (85 per cent), parking fees (83 per cent), overnight stays (62 per cent), and childcare costs (49 per cent) add further strain. The report calls for urgent improvements in IBD care and support systems to reduce both the economic and health-related burdens faced by patients in Ireland.12

Although 74 per cent of people with Crohn’s disease and colitis are covered under the HSE Drugs Payment Scheme, broader healthcare access remains a challenge. Just 29 per cent have a medical card and only 13 per cent qualify for a GP visit card, with 39 per cent finding it difficult to access GP services.

These conditions do not automatically meet the criteria for State supports, despite 98 per cent of patients believing they should. Financial pressures are evident, with 26 per cent of patients admitting they delay taking medication to make it last longer due to cost concerns.12

Conclusion

Crohn’s disease is a lifelong, relapsing-remitting condition with significant physical and emotional impact that demands a nuanced, multidisciplinary approach to diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management to improve quality of life, reduce disease burden, and promote long-term remission.

Despite significant advances in therapeutic options, including biologics, immunomodulators, and JAK inhibitors, there remains no definitive cure, and many patients face persistent symptoms, complications, and the eventual need for surgery. The complexity of its pathogenesis, involving genetic, immunologic, and environmental interactions, underlines the need for ongoing research and innovation in both pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions.

The systemic and socio-economic impact of Crohn’s disease is profound, as evidenced by high rates of extraintestinal manifestations, cancer risks, and significant financial and occupational burdens. In Ireland, the gaps in equitable healthcare access and State supports further compound the challenges faced by patients. Clinicians play a key role in ongoing assessment, treatment, education, and support.

Building a therapeutic relationship, understanding the patient’s knowledge of the disease, setting realistic goals, and addressing their physical and psychological needs are important. Patients often struggle with treatment adherence, pain, and emotional distress, including anxiety and depression.

Continuous monitoring of disease activity, treatment response, and patient wellbeing is vital to improving outcomes and quality of life.6 Optimal management must go beyond disease suppression to address broader psychosocial, nutritional, and economic aspects of care.

References

- Torres J, Mehandru S, Colombel JF, et al. Crohn’s disease. Lancet. 2017;389(10080):1741-1755.

- Health Service Executive. Crohn’s disease. Dublin: HSE; 2024. Available at: www2.hse.ie/conditions/crohns-disease/.

- AbbVie. Understanding Crohn’s and Colitis. 2023. Available at: www.crohnsandcolitis.com/crohns/causes.

- Feuerstein JD, Cheifetz AS. Crohn disease: Epidemiology, diagnosis, and management. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(7):1088-1103.

- Repiso A, Alcántara M, Muñoz-Rosas C, et al. Extraintestinal manifestations of Crohn’s disease: Prevalence and related factors. Dig Dis Sci. 2023;68(5):1234-1242.

- Ranasinghe IR, Tian C, Hsu R. Crohn disease. [Updated 2024 Feb 24]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK436021/.

- Cockburn E, Kamal S, Chan A, et al. Crohn’s disease: An update. Clin Med (Lond). 2023;23(6):549-557.

- Cushing K, Higgins PDR. Management of Crohn disease: A review. JAMA. 2021;325(1):69-80.

- Gordon H, Minozzi S, Kopylov U, et al. ECCO guidelines on therapeutics in Crohn’s disease: Medical treatment. J Crohns Colitis. 2024;18(10):1531-55.

- Health Service Executive. HSE Prescribing protocol risankizumab (Skyrizi) for the treatment of adult patients with moderately to severely active Crohn’s Disease. Available at: www.hse.ie/eng/about/who/acute-hospitals-division/drugs-management-programme/protocols/hse-prescribing-protocol-for-rizankizumab-skyrizi-.pdf.

- Doherty J, Cullen G. The spectrum of treatment for inflammatory bowel disease. Update Journal. 2024;10(9):21.

- Crohn’s and Colitis Ireland. Uncovering the hidden cost of Crohn’s and colitis. 2025. Available at: www.crohnscolitis.ie/about/news/uncoveringthecost2025/.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.