Due to a variety of factors, a child’s pain is different to that experienced by adults, and historically has been under-recognised and under-treated

Pain is “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage”. It is detected by nociceptors, which are present in most body tissues and are responsive to thermal, chemical, and mechanical stimuli.1 Noxious stimuli cause tissue injury and activate nociceptors indirectly when chemical substances (ie, potassium, serotonin, bradykinin, histamine, prostaglandins, leukotrienes, substance P) are released.

The mechanical or chemical stimuli are then converted into action potentials, which travel up to the dorsal horn at the posterior of the spinal cord. From here, the stimulus goes up to the thalamus through the anterolateral system, and also to the somatosensory cortex. Emotional and cognitive components, in conjunction with nociceptive impulses, lead to the sensation of pain.

Historically, children’s pain has been under-recognised and under-treated: Minimal or no anaesthesia was used in infant surgery even into the 1980s.2,3 We now know that the nociceptive system starts functioning at the 20th week of gestation. Studies looking at the activity around pain pathway nerve terminals have observed that nociceptive neurons do not form a specific structure in the spinal cord in preterm neonates, meaning that the premature newborn brain is actually more sensitive to pain than the adult brain, and is not always able to distinguish between noxious and innocuous stimulation.1

Children have a higher concentration of nociceptors per square meter of body surface compared to adults, and a higher level of neuromediators (meaning a higher sensitivity level). The plasticity and specific features of a child’s nervous system means that prolonged or repeated pain at a young age can increase pain sensitivity in adulthood.3

A child’s pain is different to pain that is experienced by an adult not only due to brain development, but also due to the different emotional and psychological factors that affect comprehension and response. Healthcare settings can feel unfamiliar and overwhelming for babies, children and young people, especially when meeting multiple healthcare workers.3,4 At times, children may be viewed as passive recipients of care, which can lead to poor communication, with the child not being fully heard, or not given sufficient information.

A positive healthcare experience builds confidence, supports decision-making, and improves how a child understands and manages their condition. Healthcare workers can foster this by introducing themselves, encouraging active involvement in treatment discussions, and treating patients and carers with kindness, compassion and respect.

Young people aged 16 or over are generally presumed to have capacity to make their own healthcare decisions, with parents and carers playing less and less of a role as children grow more independent. Clear, honest information – particularly about pain and how it will be managed – helps reduce anxiety. Creating a calm environment, using distraction and therapeutic play, and validating a child’s pain experience all contribute to better, more supportive care.

Paediatric pain assessment

The updated World Health Organisation (WHO) analgesic ladder advocates five principles in terms of the correct use of analgesics, which is relevant to adults and children:5

▶ Use oral forms where possible.

▶ Give at regular intervals.

▶ Administer based on pain severity, where severity is assessed by a pain intensity scale.

▶ Tailor the dose to the individual patient.

▶ Maintain attention to detail throughout the prescription of pain medications.

For optimal pain management, frequent and appropriate assessment of pain should be performed, ie, in severe pain, a pain assessment should be performed every two to four hours. The specifics of pain location, quality, duration and intensity should all be assessed and recorded, and assessments repeated as necessary.1

Due to the subjective nature of pain, self-reporting by the child is preferred, however, in pre-verbal or non-verbal children, monitoring behavioural signs (facial expression, cry, irritability, feeding, sleep disturbance and activity levels) physiological parameters (heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure, skin colour, oxygen saturation), and reports from caregivers are also useful to indicate discomfort levels.1,5 Importantly, the absence of change in physiological parameters does not mean absence of pain.

More than 60 assessment tools are available for the paediatric population, with no evidence to recommend one over any other, although it is vital that a developmentally-appropriate assessment tool should be used.

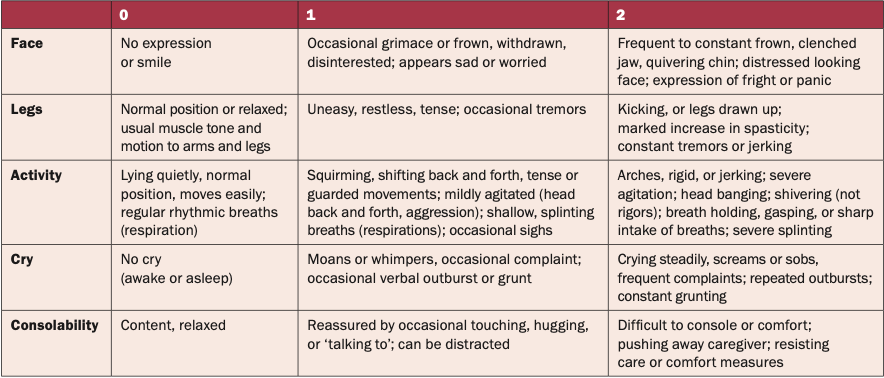

One of the most commonly used tools for young children, due to its ease of use, is the Face, Legs, Activity, Cry and Consolability Scale (FLACC) (Table 1).6 The FLACC scale is an observational tool to assess pain, validated for children from the age of two months to seven years, in many different pain conditions. A revised version (r-FLACC) is also available, which includes additional behavioural measures for improved pain assessment in children with cognitive impairment.7

To use the scale, paediatric patients who are awake should be observed for one to five minutes or longer. If asleep, they should be observed for five minutes or longer. Based on observations during this time each category is scored on the 0–2 scale, which results in a total score of 0–10:6

▶ 0: Relaxed and comfortable.

▶ 1–3: Mild discomfort.

▶ 4–6: Moderate pain.

▶ 7–10: Severe discomfort or pain or both.

This score can then be used to guide pain management decisions.

Pain management

Acute pain

Pain relief can make examination and testing of the patient easier, meaning that a diagnosis may be more easily made. There is evidence that early treatment of pain does not affect diagnostic accuracy.1

In infants and young children, the following evidence-based methods to prevent or treat pain can be offered, especially for acute needle pain:8

▶ Topical anaesthesia, ie, lidocaine and prilocaine (eg, Emla cream).

▶ Sucrose or breastfeeding for infants aged 0-12 months.

▶ Comfort positioning, such as swaddling or skin-to-skin for infants; sitting upright on a parent or carer’s lap for those aged six months and older.

▶ Age-appropriate distraction, ie, toys, books, blowing bubbles, apps, games, electronic devices.

First-line pain medications, paracetamol and ibuprofen, can be used as monotherapy or together for more severe pain, with or without additional physical and psychological approaches.1

Ibuprofen is more effective than paracetamol for treatment of acute pain like musculoskeletal trauma, headache, and dental pain, and has a similar safety profile. In fact, ibuprofen has comparable efficacy to oral morphine for treatment of sprains, fractures, and post-orthopaedic procedures and tonsillectomy, with a superior safety profile.

For dental pain and pain post-tonsillectomy, the combination of paracetamol and ibuprofen is more effective than paracetamol alone. Where first-line options are not working for children in acute severe pain, opioids can be used. Intranasal fentanyl is a common choice due to its effectiveness and minimal distress at administration.

Morphine is the most common intravenous agent. Any patient being treated with opioids must be monitored and have the medication titrated as appropriate.

Multimodal analgesia, which combines different classes of pain-relieving drugs and non-pharmacological approaches, acts synergistically for more effective pain control – and has fewer side-effects – than a single analgesic or modality.8 When used successfully, non-pharmacological measures are able not only to reduce pain and anxiety, but also reduce the amount of medication required.1,3

Effective multimodal analgesia approaches include:8

▶ Medications: Basic analgesia, ie, paracetamol, NSAIDs, COX-2 inhibitors; opioids, ie, tramadol, morphine, methadone; adjuvant analgesics, ie, gabapentin, clonidine, amitriptyline.

▶ Rehabilitation: Physical therapy, graded motor imagery, occupational therapy, psychology (ie, cognitive behavioural therapy).

▶ Additional non-pharmacological modalities: Diaphragmatic breathing, bubble blowing, hypnosis, progressive muscle relaxation, biofeedback, aromatherapy, acupressure, acupuncture; physical properties such as massage, heat compresses, ice packs, repositioning.2

Anxiety and mood can also impact pain experience. By offering patients a chance to express any fears or concerns, this gives an opportunity to provide reassurance by, ie, reviewing their pain plan.2

Chronic pain

Chronic pain (lasting for more than three months) is reported in 11-to-38 per cent of children.1 As in adults, lower socioeconomic status, anxiety, depression and low self- esteem are associated with chronic pain occurrence. The most common types of chronic pain in children are headaches, abdominal pain, and musculoskeletal pain.

The best way to manage chronic pain is by using multiple approaches: Psychological, physical, occupational and pharmacological; and individualised to the patient, with the primary aim being functional improvement rather than strictly pain reduction. These strategies are likely to be more successful with the involvement of the parents/caregivers.

Involving parents and caregivers in the clinical discussion around pain management of their child informs and empowers them to help in providing optimal pain management at home. Psychological strategies like distraction and physical strategies like appropriate wound dressing or encouraging physical activity are useful, teachable skills to take home. Adequate analgesics should also be prescribed.

Untreated pain

Accurate assessment of paediatric pain can be extremely difficult. In paediatric patients admitted to hospital, pain may not be assessed adequately or regularly. There are a myriad of reasons for this, including:1,2,3

▶ Limited experience and training in acute pain management in children.

▶ Crowded emergency rooms in the hospital environment.

▶ Individual clinical condition.

▶ Variations in children’s age, development, communication levels, personalities and temperaments.

▶ Lack of clinical standards.

▶ Underuse of pain scoring tools.

▶ Old misconceptions (ie, ‘children do not feel as much pain as adults’).

Untreated acute pain (due to, ie, disease, trauma, surgery, interventions or disease directed therapy) can lead to fear or avoidance of future engagement with the healthcare system, therefore adequate pain management is vital.8 Even untreated needle pain (from, ie, vaccinations, blood draws, cannulations) can result in needle phobia, hyperalgesia, and anxiety about the procedure, resulting in avoidance of healthcare.

Exposure to severe pain without sufficient pain management is ultimately linked with increased risk of chronic pain, anxiety and depressive disorders in adulthood; increased morbidity and mortality, and increased burden on healthcare resources.1

Conclusion

Pain in children is a complex sensory and emotional experience, influenced by developing neurological pathways, making early and repeated pain particularly impactful across the lifespan. Accurate and developmentally-appropriate assessment is essential to guide management choices that may include pharmacological and/or non-pharmacological strategies. Effective, compassionate pain management not only reduces suffering, but also prevents long-term consequences such as chronic pain, anxiety, needle phobia, and avoidance of healthcare.

‘Green whistle’ for children approved for emergency pain relief following clinical trial

A major international clinical trial, led in Ireland by a team from Children’s Health Ireland (CHI) (Prof Michael Barrett, with Co-Investigator Dr Carol Blackburn, and Research Nurses Madeleine Niermeyer, Ellen Barry, and Rachel Gallagher, supported by the emergency department team), has found that methoxyflurane, delivered via the familiar ‘green whistle’ (Penthrox), provides significant and rapid pain relief for children aged six years and older with acute trauma injuries.

The study, conducted through the CHI Clinical Research Centre, which is supported by the Health Research Board (HRB) and Children’s Health Foundation (CHF), marks a major step forward in emergency paediatric care.

The MAGPIE trial (Methoxyflurane analgesia in paediatric injury emergency) evaluated the use of methoxyflurane in over 240 children aged six to under 18 years presenting with moderate or severe pain in emergency settings. The results are clear: Children who received methoxyflurane experienced a faster and greater reduction in pain compared to those given a placebo treatment.

Children in pain described the pain relief while inhaling the green whistle. Of note, only one-in-10 of those treated with methoxyflurane needed rescue or extra pain medication, compared to one-in-three in the placebo group – highlighting its effectiveness as a first-line treatment in emergency care. While some mild side-effects such as dizziness, euphoria, and altered taste were more common in the methoxyflurane group, these were expected, short-lived and well-tolerated.

The MAGPIE trial was led by UK Chief Investigator Dr Stuart Hartshorn, Birmingham Children’s Hospital, and conducted utilising the international Paediatric Emergency Research United Kingdom and Ireland (PERUKI) research network. It builds on previous adult trials and now confirms methoxyflurane’s effectiveness and safety for children in clinical settings.

The trial has now concluded and its findings support wider paediatric adoption of methoxyflurane as part of standard pain relief protocols in emergency departments and pre-hospital settings.

“The success of the MAGPIE trial is a testament to the dedication and professionalism of our entire team in CHI. Delivering a randomised controlled trial for children in pain in a busy 24/7 paediatric emergency department is no small feat, balancing emergency care with rigorous research protocols, all while supporting children and families in distress. I’m incredibly proud of our staff, whose commitment to care made it possible to carry out this important study to the highest standard. The green whistle offers an option that can be delivered quickly, effectively addressing pain, and improving the care experience for patients and their families. We are very proud to have been part of its approval,” said Prof Michael Barrett, Irish Lead and Co-Investigator for the MAGPIE trial, and Paediatric Emergency Medicine Consultant, CHI at Crumlin.

References

1. Trottier ED, Ali S, Doré-Bergeron MJ, Chauvin-Kimoff L. Best practices in pain assessment and management for children. Paediatr Child Health. 2022;27(7):429-37

2. Rodkey EN, Riddell RP. The infancy of infant pain research: The experimental origins of infant pain denial. J Pain. 2013;14(4):338-50

3. Pancekauskaite G, Jankauskaite L. Paediatric pain medicine: Pain differences, recognition, and coping with acute procedural pain in the paediatric emergency room. Medicina (Kaunas). 2018;54(6):94

4. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Babies, children and young people’s experience of healthcare. NICE guideline NG204. London: NICE; 2021. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng204

5. Gai N, Naser B, Hanley J, Peliowski A, Hayes J, Aoyama K. A practical guide to acute pain management in children. J Anaesth. 2020;34(3):421-33

6. Children’s Health Ireland. FLACC behavioural pain assessment scale. Dublin: Children’s Health Ireland; 2017. Available at: https://media.childrenshealthireland.ie/documents/Pain-FLACC-Behavioural-Pain-Assessment-Scale-.pdf

7. Malviya S, Voepel-Lewis T, Burke C, Merkel S, Tait AR. The revised FLACC observational pain tool: Improved reliability and validity for pain assessment in children with cognitive impairment. Paediatr Anaesth. 2006;16(3):258-65

8. International Association for the Study of Pain. Pain in children: Management. Fact sheet. Washington (DC): IASP; 2021. Available at: www.iasp-pain.org/resources/fact-sheets/pain-in-children-management/

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.