An overview of the current guidelines on the assessment and management of lower limb wound presentations in general practice

Lower limb ulcers are a common presentation in general practice. They are defined as a defect in the dermis located on the lower limb (HSE National Wound Management Guidelines 2018). Many of these patients present with symptoms such as leaking legs, advanced oedema, ulceration pain and malodour. It is estimated that the population of over-65s in Ireland will triple over the next few decades, which will likely increase the prevalence and incidence of wounds and have a major impact on healthcare finances.

The cost associated with management in Ireland is poorly appreciated; however Gillespie et al (2016) estimated costs of €788.5 million per annum were spent on wound care in the Irish healthcare service. Guest et al (2015) found that the management of wounds and associated co-morbidities costs the NHS in the UK £5.3 billion per annum and estimated that 1.5 per cent of the adult population in the UK is affected by active leg and foot ulceration.

Within the study Guest et al (2015) reported significant variation in care provision and the author suggests that similar variations in care exist in the Irish healthcare service. The UK has implemented a national wound care strategy to address these anomalies with a specific strategy for the management of lower limb ulcers (2020). Whilst we are uncertain of the true extent of lower limb ulcers in the Irish healthcare setting, the majority of these wounds are caused by chronic venous insufficiency.

Arterial disease is prevalent in 15-to-20 per cent of presentations and other diseases, such as dermatological, immunological, skin tumours, and trauma, account for the remainder (HSE 2018). Leg ulcers can be time consuming and difficult to manage in general practice. This is further compounded by varied or poor access to specialised services and the advanced wound care products required to safely and effectively manage these wounds. The purpose of this article is to inform staff working in general practice in Ireland of the current guidelines on the assessment and management of lower limb wound presentations. The information provided is based on the HSE National Wound Management Guidelines (2018) and the clinical practice recommendations therein.

Whilst we are uncertain of the true extent

of lower limb ulcers in the Irish healthcare

setting, the majority of these wounds are caused

by chronic venous insufficiency

Basic assessment of lower limb wounds

One of the key questions in the guidelines asks who should assess patients who present with lower limb ulcerations. In general practice settings this can either be the GP or the nurse. The HSE National Wound Management Guidelines (2018) recommends that a clinician should possess post basic education and training in the assessment and management of wounds in order to comprehensively assess and put in place an evidence-based treatment plan to manage these patients. When undertaking a lower limb assessment the following factors should be assessed:

- Medical and surgical history including assessment of comorbidities and medications.

- Previous or current DVT.

- History of phlebitis.

- Surgery or trauma of the affected leg.

- Prolonged standing or sitting.

- Physical examination including detailed examination of both lower limbs, the wound itself, and the surrounding skin.

- Leg wound history to include- duration, size.

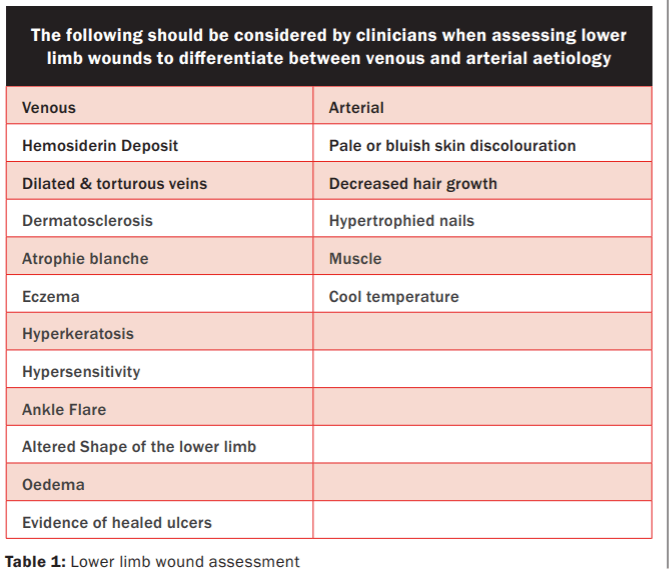

- Previous wounds and treatments used. Vascular assessment ( se Table 1 for indicators of aetiology), ABPI, pulse palpation.

- Previoua venous disease, presence of varicose veins or chronic skin changes.

- Mobility and functional status.

- Pain history.

- Biochemical investigations where appropriate

Ankle brachial pressure index

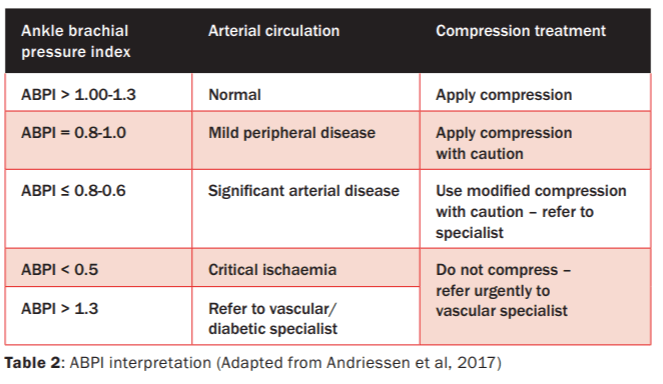

(ABPI) and its interpretation The ABPI is an investigation that compares ankle systolic pressure to central systolic pressure and the calculated index or result signifies the absence or presence of arterial disease, which will directly impact how the wound is managed. It is important to note that most general practices do not undertake this assessment, however, many public health centres have trained nurses who can provide this assessment. The ABPI result must be interpreted (See Table 2) in conjunction with pulse palpation and overall clinical assessment. If pulses are palpable and there is no history of diabetes or peripheral arterial disease, lower limb wounds should be placed in compression therapy (HSE National Wound Management Guidelines 2018). Application of compression therapy must be undertaken by a competent practitioner.

General lower limb wound care –

back to basics

The importance of making a positive impact from the first consultation with a patient presenting with a wound cannot be underestimated. Engaging in a positive relationship is underpinned by providing the patient with the assurance that we as clinicians know what we are doing or can refer on to the appropriate specialist for further assessment. If a patient needs to be referred on for specialist opinion it is important to do so at the first contact and a plan put in place that will address the main issue that the patient is presenting with in the interim; for example, malodour, exudate management or pain. Once a treatment plan is adhered to, ongoing evaluation is required to determine whether this has made a positive impact on the wound and the patient. Much has been written pertaining to variation in wound assessment and treatment in clinical practice (Guest et al, 2015). An expert group was formed and the World Union of Wound Healing Societies (WUWHS) published a consensus document (Strategies to reduce practice variation in wound assessment and management: The TIME Clinical Decision Support Tool 2020). The tool is widely used in wound care assessment and management.

It was first developed by Schultz et al (2003) and has been updated to address changes in wound care practice (Moore et al 2019). The premises of the tool are to provide a structured approach to wound assessment, including holistic assessment of the patient and their wound. The tool was updated to assist clinicians who do not have specialist training in wound care management to assess patients and their wounds in a manner that provides a structured approach with clear rationale for treatment decisions. The TIME Tool assists in aiding the clinician to assess the tissue type in the wound bed, presence of inflammation or infection, moisture balance and the status of the wound edge. It gives a pictorial guide to descriptors and dressing types suitable to each descriptor and provides a structured wound management approach that enables consistency, which then contributes to better patient outcomes.

Wound hygiene

Wound hygiene has become an important concept in wound care (International Consensus Document Wound Hygiene, 2020). The concept was devised to address the growing burden of hard-to-heal wounds, particularly in relation to biofilm and wound infection identification and management. The consensus document promotes the application of a wound cleansing strategy to improve the management of hard-to-heal wounds through disruption of biofilm present in the wound bed, and prevention of its reformation. It consists of two stages with overlapping strategies:

- Cleansing the wound and peri- wound skin.

- Debridement as necessary, which may be more aggressive initially but reverts to maintenance debridement when clinically indicated.

- Refahioning the wound edge.

- Dressing the wound.

The document proposes that all hard-to-heal wounds contain biofilm (International Consensus Document Wound Hygiene, 2020) and in the absence of good wound hygiene, progression to failure to heal becomes a real threat despite the use of dressings. Whilst it may seem strange that a strategy needs to be employed to promote wound cleansing, let us as practitioners reflect back on our practice and last dressing change. When cleansing the wound did you simply gently swipe moistened gauze over the wound bed itself and proceed to dressing or did you cleanse the wound bed aggressively enough to remove devitalised tissue, debris and biofilm? Moreover, did you cleanse the peri-wound tissue to remove skin scales or callus or built-up dressing debris? This is perhaps a major failing in wound care practice today and failure to do so encourages growth of biofilm and transitioning of a wound to the hard-to-heal stage.

Debridement is also a vital part of wound hygiene and whilst the term itself may lend one to think of a scalpel, there are many forms of wound debridement that result in removal of necrotic tissue, slough, debris and wound biofilm (HSE National Wound Management Guidelines, 2018).

Wound edges can provide a sanctuary for biofilm to form and refashioning the edges in the aforementioned strategy alludes to simply removing necrotic or crusty material from the overhanging wound edges. It is also important to ensure the skin edges are aligned to facilitate the advancement of epithelial cells and in turn promote wound contraction or closure (International Consensus Document Wound Hygiene, 2020).

Finally, in order to address the remaining biofilm or prevent overt formation or delay growth of biofilm it is important to use appropriate dressings (HSE National Wound Management Guidelines 2018). These dressings may contain antimicrobial or anti-biofilm properties (Schultz et al 2017). Further consideration must be given to patient choice and engagement and to availability. Dressings available can be prescribed for patients and dispensed in their local pharmacy.

The pharmacy will have a list of what products are available on the medical card scheme. Referral to the local primary care centre with access to a dressing clinic can also be arranged particularly for patients with wounds that are likely to become hard to heal. As previously stated, the number of people living with complex conditions is increasing, which directly impacts on the increasing number of hard-to-heal wounds with both financial and social implications in a health service that has finite resources. Tackling these wounds in the early stages of onset may circumvent later complications and promote better patient outcomes.

References

Gillespie P, Carter L, McIntosh C, and Gethin G. (2016) Estimating the Healthcare Costs of Wound Care in Ireland. Unpublished poster presentation at EWMA 2016, May 10-13 2016, Bremen, Germany.

HSE National Wound Management

Guidelines 2018 Available at: www.hse.ie/eng/about/who/onmsd

Moore Z, Dowsett C, Smith G et al. (2019) TIME CDST: an updated tool to address the current challenges in wound care. Journal of Wound Care 28(3): 154-61

Murphy C, Atkin L, Swanson T. et al (2020) International consensus document. Defying hard to heal wounds with an early antibiofilm intervention strategy: w ound hygiene.

Journal of Wound Care 29(Suppl 3b): S1-28.

National Wound Care Strategy

Programme (2020). Recommendations

for Lower Limb Ulcers

Schultz GS, Bjarnsholt T, James GA et al. (2017) Consensus guidelines for the identification and treatment of biofilms in chronic non-healing wounds. Wound Repair and Regeneration 25: 744-757

Schultz GS, Sibbald RG, Falanga V, et al (2003). Wound bed preparation: a systematic approach to wound management. Wound Repair and Regeneration 11:1-28

World Union of Wound Healing Societies (2020) Strategies to reduce practice variation in wound assessment and management:

The TIME Clinical Decision Support Tool. London: Wounds International. Available at:

www.woundsinternational.com

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.