Reference: November 2025 | Issue 11 | Vol 11 | Page 12

In just a few years, semaglutide (Ozempic/Wegovy) and tirzepatide (Mounjaro) have gone from niche type-2 diabetes (T2D) treatments to mainstream culture, hailed as ‘miracle’ weight-loss injections. Current estimates suggest one-third of adults worldwide are living with obesity, a major risk factor for developing T2D, cancer, and cardiovascular disease, alongside over 200 life-threatening complications.1

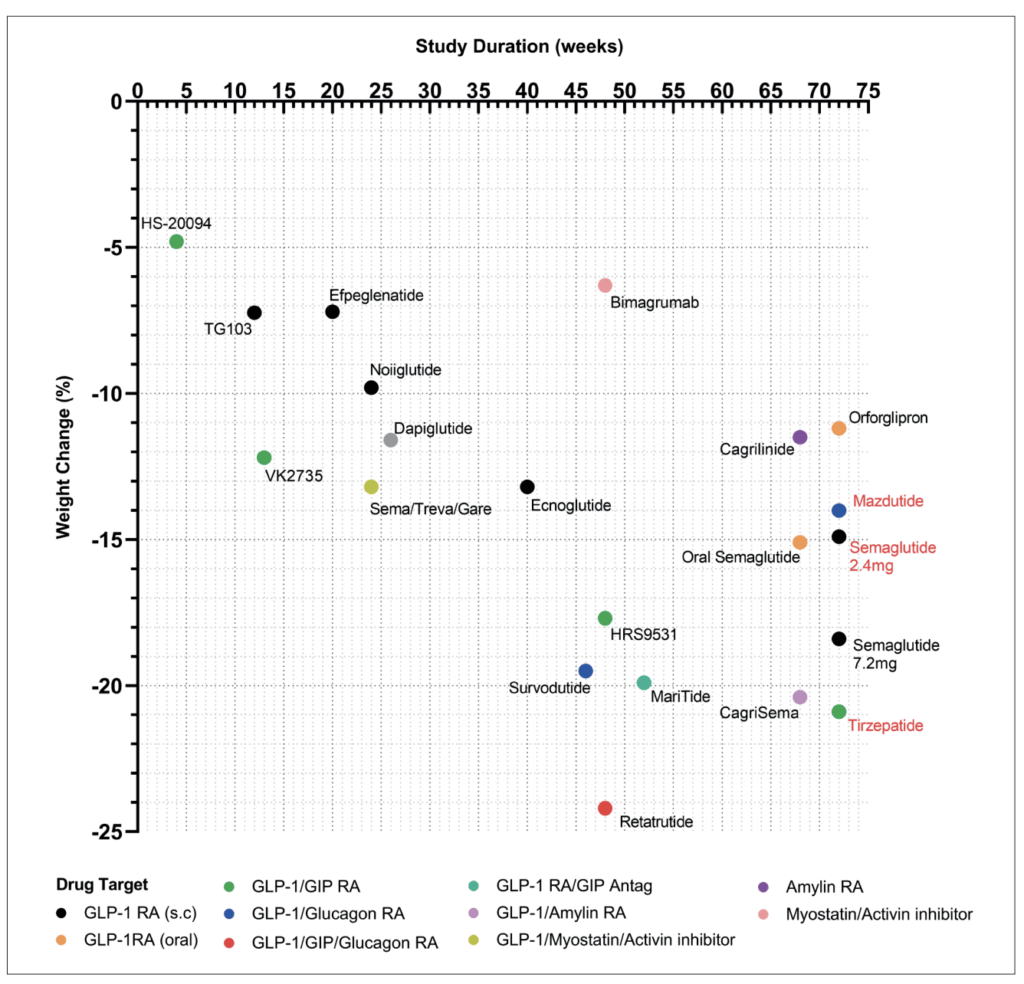

These medications, alongside alarming global rates of obesity and associated morbidity, are reshaping societal views on obesity, emphasising the urgency to actively treat this disease. With more than 10 leading pharmaceutical companies developing the next generation of weight loss drugs (Figure 1), we aim to summarise this burgeoning new wave of weight loss pharmacotherapies due to arrive very soon.

GLP-1 RAs

Ozempic and Wegovy are both drugs that activate the glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor. Simply put, these drugs mimic the natural hormone GLP-1 that helps control blood sugar and appetite and delays absorption of calories. This class of drugs was initially developed in the late 1990s and early 2000s, with exenatide, the first twice-daily GLP-1 approved for T2D in 2005.

Since its approval, its strong efficacy and safety profile have led to the development of stabilised, longer-acting GLP receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) that allow for once daily (liraglutide) and once weekly (semaglutide) dosing, respectively.2 These drugs additionally promote weight loss on top of their glucose-lowering efficacy, hence liraglutide and semaglutide are now approved for treatment of obesity.

Currently, semaglutide is prescribed at a 2.4mg dose for treating obesity;3 however, recent clinical studies have trialled the use of 7.2mg semaglutide in obesity treatment. Interestingly, tripling the dose did not result in significant improvements in weight loss or HbA1c (glycated haemoglobin), but a larger proportion of participants did achieve weight loss greater than 20-25 per cent.4

Encouragingly, the side effect profile of 7.2mg was comparable to that of 2.4mg semaglutide. Given that the efficacy similarity between the two doses was similar, it may be that we have reached saturation point with GLP-1 RAs, in which increasing the dose further results is a diminishing return and fails to augment clinically meaningful improvements in weight loss or glucose control (Figure 1).

However, GLP-1 RAs have also been found to exert multi-organ benefits to improve cardiac/renal health and neuroprotection.5 It is currently unclear whether these higher doses of GLP-1 RAs could confer better cardio-/renal-/neuroprotection.

Following on from this, efpeglenatide, a modified exendin conjugated to the fragment crystallizable (Fc) region of human immunoglobulin (Ig), possesses a pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic profile supporting once monthly administration. In vitro studies demonstrate efpeglenatide has a lower binding affinity and faster dissociation for GLP-1 R compared to liraglutide, and as a result has less receptor internalisation, producing a super-agonistic effect.6

In people with obesity, efpeglenatide significantly reduced body weight versus placebo by -6.3 kg (6mg every two weeks) and -7.2kg (6mg once weekly), and improved glycaemic and lipid profiles after 20 weeks of treatment (Figure 1).7

Sub-analysis of this AMPLITUDE-O trial revealed that only 12 per cent of the drug’s effect on HbA1c was attributable to weight loss, suggesting that the incretin action of efpeglenatide plays a pivotal role in glycaemic control.8

Similarly, TG103 is a fusion protein comprised of two GLP-1 molecules fused to an Fc fragment via IgG, resulting in a stable GLP-1 RA permitting once weekly administration.9 Currently in phase 2/3 development (NCT05299697 and NCT05997576), initial phase 1 trials reveal 7.2 per cent weight loss following once weekly dosing at 7.5mg for 12 weeks (Figure 1).9

Biased GLP-1 RAs

Traditional GLP-1 RAs exhibit unbiased agonism in which they bind to the GLP-1 R to trigger both cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) and beta-arrestin signalling pathways. cAMP-PKA (protein kinase A) signalling cascades bring about the insulinotropic and appetite-suppressing actions of GLP-1 within their respective target cells, whilst beta-arrestin signalling is responsible for receptor recycling.10 Accordingly, cAMP generation and beta-arrestin recruitment assays are now implemented in drug development to screen for compounds that produce cAMP whilst having minimal beta-arrestin recruitment.

Ecnoglutide is a biased GLP-1 RA that favours cAMP production ahead of beta-arrestin recruitment. Its structure consists of acylation at Lys30 and a valine substitution at position 8, which confers cAMP bias.10,11 As a result, the GLP-1 R remains active on the cell membrane to potentiate signalling (eg, enhanced insulin secretion in pancreatic beta-cells).

Unlike semaglutide, ecnoglutide is comprised of entirely naturally occurring amino acids, and can therefore be synthesised at lower costs. Whether this biased GLP-1 RA will be as effective as tirzepatide remains to be seen (Figure 1), and results from upcoming phase 3 trials (NCT05222912 and NCT05813795) should answer this.

Oral GLP-1 RAs

Currently, the above described GLP-1 RAs are self-administered subcutaneously. To improve patient adherence and logistical storage/distribution, several drug companies are developing orally active GLP-1 RAs, that are stable at room temperature, including oral semaglutide (Novo Nordisk) and small molecular GLP-1 RAs orforglipron (Eli Lilly) and danuglipron (Figure 1).

To enable oral administration, semaglutide has been formulated with a gastric absorption enhancer, sodium-N-[8-(2-hydroxybenzoyl)amino] caprylate (SNAC).12 This enhancer elevates local pH to protect semaglutide from gastric proteolytic degradation and mediates absorption across the gastric epithelium.13

Oral semaglutide has been trialled at both 25mg4 and 50mg14 doses, resulting in -13.6 per cent and -15.1 per cent weight loss, respectively, with the lower dose eliciting fewer adverse gastrointestinal events (74% vs 86%). Based on these data, the 50mg oral dose matches the efficacy of injectable semaglutide 2.4mg.

Orforglipron (LY3502970) is a non-peptide, cAMP biased GLP-1 RA with a half-life of ~36 hours permitting daily dosing.15 In people with obesity, orforglipron reduced body weight by 11.2 per cent following 72 weeks administration.4 Orforglipron is the first non-peptide GLP-1 RA to progress to phase 3 trials assessing its efficacy in people with obesity (ATTAIN-1/2), T2D (ATTAIN-3), and as a comparison against tirzepatide (ATTAIN-4). Results of these trials are expected to be published in 2027.

Danuglipron is a small molecule GLP-1 RA with nanomolar affinity for the human GLP-1 R.16 In a phase 2 study, danuglipron reduced body weight in people with obesity by 17.6 per cent; however, high discontinuation rates (~40-50%) were noted due to treatment-related gastrointestinal side effects.17 One participant experienced drug-induced liver injury, and as a result, Pfizer have discontinued development of danuglipron.18

GLP-1 + GIP RA

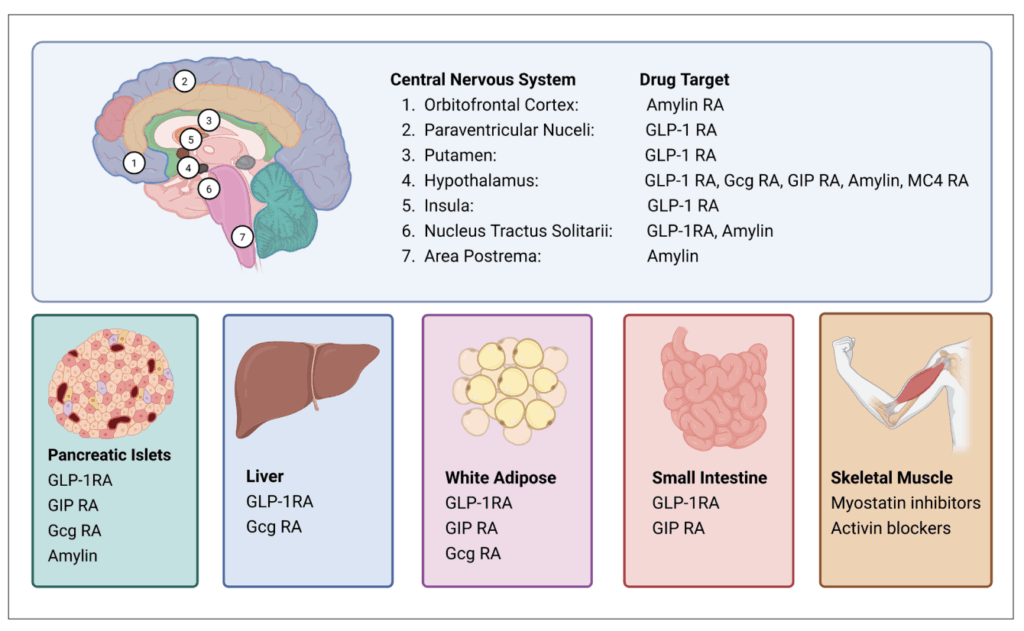

Tirzepatide is the first GLP-1/glucose-dependent insulinotropic (GIP) dual RA approved for T2D and obesity. Developed by Eli Lilly, this modified peptide exhibits higher affinity for GIP R and biased agonism against the GLP-1 R, favouring cAMP over beta-arrestin signalling. By leveraging GIP R networks within the pancreas and brain, tirzepatide enhances insulin secretion, fat utilisation, and weight loss (Figure 2). SURMOUNT-1 demonstrated 22.5 per cent weight loss following 72 weeks of once weekly 15mg tirzepatide (Figure 1).19

SURMOUNT-2 demonstrated that tirzepatide elicited 18.4 per cent weight loss in people with obesity who had already achieved ≥5 per cent weight loss via lifestyle modification.20 SURMOUNT-4 investigated maintenance of weight loss, with tirzepatide withdrawal resulting in 14 per cent weight regain within 16 weeks of drug cessation.21 A direct comparison (SURMOUNT-5, NCT05822830) has found tirzepatide to be superior to semaglutide in respect to 72-week reductions in weight and waist circumference (Figure 1).22

As a result, tirzepatide is currently the lead weight loss drug, with new therapies aiming to surpass tirzepatide, or match its efficacy, alongside a more favourable dosing strategy and/or side effect profile.

GLP-1 RA + GIP R antagonism

Of peculiar interest to the research community are the findings that both GIP R agonism and GIP R antagonism improve the metabolic benefits of GLP-1 RA. This therapeutic avenue was initially established through early exciting preclinical observations with peptide-based drugs by Irwin and colleagues at Ulster University, Coleraine.23 Since then, leading metabolism labs worldwide have actively focused on unravelling these mechanisms to solve this paradox, with several hypotheses being explored.24

One hypothesis is that chronic GIP R agonism results in functional antagonism due to desensitisation to ligand-mediated stimulation.25 Second, it is suggested that GIP R agonists and antagonists act on different central nervous system (CNS) regions (Figure 2), and both independently play a role in weight and glycaemic control.26 Thirdly, it is thought that the improved efficacy of tirzepatide is due to biased GLP-1 R action rather than the additional GIP R agonism.

Despite this uncertain mechanism, maridebart cafraglutide (MariTide), developed by Amgen, is a GLP-1 RA linked to a GIP R antagonist antibody, currently in trials for obesity as a once-monthly treatment. Phase 1 trials reported MariTide was well tolerated with 14.5 per cent weight loss following 12-week dosing.27 The first 52-week data from the phase 2 trial was recently published, demonstrating 19.9 per cent weight loss without plateau.28

Part 2 of the trial is ongoing for a further 52 weeks to investigate if plateau weight loss occurs. Concerns over GIP R antagonism on bone health have previously been reported,29 however, current MariTide studies have not observed any impact on bone health.28 Whether this is consistent over long-term use remains to be seen. Findings from part 2 of the phase 2 trial and the upcoming phase 3 trial will shed light on this.

GLP-1 + glucagon

Mimicking the action of the proglucagon-derived peptide oxyntomodulin, GLP-1 and glucagon (GCG) dual receptor agonists reduce energy intake (via GLP-1 R) and increase energy expenditure (via GCGR) to promote weight loss (Figure 2). This GCG-mediated increase in metabolic rate and potential hepatic benefits underpins its rationale for combining with GLP-1 for an anti-obesity medication.30

Mazdutide is an oxyntomodulin analogue, stabilised by a fatty acid to extend its half-life and allow once-weekly administration. Developed by Eli Lilly, initial phase 1 trials commenced in December 2016 (Figure 1), with mazdutide first approved in China for weight management (June 2025) and glycaemic control in T2DM (September 2025).31

Trials are currently under way comparing efficacy against semaglutide in people with obesity with early T2D (DREAMS-3), in people with obesity and MAFLD (metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease) (GLORY-3), and in people with obesity and obstructive sleep apnoea (GLORY-OSA). Lastly, mazdutide is being trialled in people with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) (NCT06937749) or alcohol use disorder (NCT06817356).

Survodutide (BI 456906) is another agonist of both GLP-1 and GCG receptors, developed as stable fatty acid acylated peptide, permitting once weekly dosing.32 In people with obesity, survodutide elicited 18.7 per cent weight loss at week 46 with over 40 per cent of participants achieving >20 per cent weight loss and a safety profile similar to other peptide-based therapies (Figure 1).33

Current phase 3 trials are assessing efficacy over 76 weeks (NCT06066515) and cardiovascular outcomes (SYNCHRONIZE-CVOT, NCT06077864), expected to be completed January and July 2026, respectively. Beyond obesity and diabetes, survodutide is also being trialled for improvement of MASH (NCT04771273; Figure 2).

GLP-1 + GIP + glucagon

Since both combinations of GIP and GCG produce added benefits when combined with GLP-1, it was logical to consider that all three hormone agonists combined may yield superior therapeutic benefits (Figure 2). This idea was investigated early on within the lab at Ulster University, Coleraine.34 In subsequent preclinical studies, triple agonism exceeded GLP-1/GIP dual-agonism on weight loss benefits.35

Currently, retatrutide (LY3437943), developed by Eli Lilly, is the lead triple-agonist in clinical development for obesity and T2D (Figure 1). In people with obesity, once weekly retatrutide (12mg) over 48 weeks yielded 24.2 per cent reduction in body weight, with 83 per cent achieving weight loss >15 per cent at an acceptable tolerance level (6-16% discontinuation).36

Phase 3 trials are ongoing with TRIUMPH-1 recruiting 2,100 participants with obesity to receive placebo or retatrutide for 89 weeks (NCT05929066). Similarly, TRIUMPH-3 is under way to assess weight loss in participants with obesity and established cardiovascular disease (NCT05882045). Both TRIUMPH-1 and TRIUMPH-3 have anticipated completion dates of May and February 2026, respectively.

GLP-1 + amylin

Amylin is a hormone produced by pancreatic beta-cells and co-secreted alongside insulin. Amylin acts peripherally to delay gastric emptying and suppress alpha-cell glucagon secretion post meal.37 Within the CNS, amylin acts at several brain regions to regulate satiety (Figure 2).

As a monotherapy cagrilintide, a stablised amylin analogue, produced significant weight loss, albeit inferior to GLP-1 RAs; however, when administered in combination with GLP-1 RAs (CagriSema) it appears to exert synergistic effects (Figure 1).38 Phase 3 trials in people with obesity (REDEFINE-1) or people with obesity plus T2D (REDEFINE-2), CagriSema achieved 20.4 per cent and 13.7 per cent weight loss respectively.39,40

Trials are currently ongoing to assess the cardioprotective effects of CagriSema (REDEFINE-3), whilst two other trials are directly comparing CagriSema versus semaglutide (REDEFINE-6) or tirzepatide (NCT06131437). These findings will inform us whether CagriSema achieves superior weight loss compared to currently approved incretin agonists whilst maintaining cardiovascular benefits.

Melanocortin

The leptin-melanocortin system, in particular melanocortin 4 receptor (MC4R), plays a pivotal role in weight regulation (Figure 2). Rare genetic variants in the MC4R pathway (proopiomelanocortin deficiency or leptin receptor deficiency) can result in early-onset obesity. Setmelanotide, a MC4R agonist, is approved for treatment of this specific genetic obesity resulting in 10 per cent weight loss at one year and a 30-40 per cent reduction in hunger scores.41

It is unclear whether setmelanotide achieves notable weight loss in common obesity – two phase 2 clinical trials have been conducted in people with obesity (NCT02041195, NCT01749137); however, no results are reported.

Activin/myostatin inhibitors

In response to reports of loss of lean mass associated with GLP-1 RAs,42 scientists have turned their attention on muscle mitogens, initially developed for muscle atrophy disorders. The myostatin/activin pathways has been identified as a physiological axis responsible for inhibiting muscle growth.43 In this regard, bimagrumab, a monoclonal antibody against activin II receptors, has been trialled in people with T2D and obesity, resulting in 6.5 per cent weight loss over 48 weeks, alongside a 3.6 per cent increase in muscle mass (Figure 1).44

As a result, trials are now underway combining these myostatin/activin inhibitors with semaglutide and tirzepatide to assess whether they amplify weight loss whilst sparing muscle mass. Interim results from the phase 2 COURAGE trial, in which semaglutide is co-administered with trevogrumab (anti-myostatin) and garetosmab (anti-activin A), show that 26-week triple therapy results in 13.2 per cent weight loss (Figure 1) with an increase of 27.3 per cent fat loss whilst preserving 80.9 per cent of lean mass compared to semaglutide.45 Studies are under way to determine the functional capacity of this conserved muscle mass.

Limitations and concerns

The long-term cardiovascular safety of these new drugs for T2D and obesity needs to be determined. Clinical vigilance to ascertain risk of rare pathologies such as pancreatitis, retinopathy, and their impact on fertility is required. Among all clinical studies, there appears to be 10 per cent of participants that do not respond to GLP-1 based obesity therapies.

In-depth analyses into this specific population would be useful to identify biomarkers that can predict a person’s responsiveness to GLP-1 based therapies. Lastly, a key limitation is required use to maintain weight loss, with many reports showing significant weight regain upon cessation of pharmacotherapy.21 This raises concerns about the lifelong adherence, cost, and long-term safety.

Economic and ethical concerns on appropriate use also need to be addressed. Drug development is an expensive process with these drugs likely to come at a high price. Combined with supply issues and high demand, real world access may require patient stratification for those in most need. With increasing rates of obesity amongst children, the sociomedical debate regarding the use of these drugs in young people is ongoing.

Final remarks

There is a promising horizon of new obesity pharmacotherapies on the way (Figure 1). Identifying which molecular targets combine well with GLP-1 has yielded dual- and triple-acting compounds set to achieve superior weight loss and cardiovascular benefits, based on the diverse organs and complementary pathways they act upon (Figure 2). This wave of drugs promises to achieve weight loss of ≥25 per cent, a feat previously only possible by surgical approaches (Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy). The impact of Ozempic and related drugs has been remarkable, but there is clearly still more to come in this field.

References

- Kinlen D, Cody D, O’Shea D. Complications of obesity. QJM. 2018;111(7):437-443. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcx152.

- Knudsen LB, Lau J. The discovery and development of liraglutide and semaglutide. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2019;10:155. doi:10.3389/fendo.2019.00155.

- Singh G, Krauthamer M, Bjalme-Evans M. Wegovy (semaglutide): A new weight loss drug for chronic weight management. J Investig Med. 2022;70(1):5-13. doi:10.1136/jim-2021-001952.

- Wharton S, Freitas P, Hjelmesæth J, et al. Once-weekly semaglutide 7.2mg in adults with obesity (STEP UP): A randomised, controlled, phase 3b trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2025;13(11):949-963. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(25)00226-8.

- Tanday N, Flatt PR, Irwin N. Metabolic responses and benefits of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor ligands. Br J Pharmacol. 2022;179(4):526-541. doi:10.1111/bph.15485.

- Trautmann ME, Choi IY, Kim JK, Sorli CH. Pre-clinical effects of efpeglenatide, a long-acting glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist, compared with liraglutide and dulaglutide. Diabetes. 2018;67

(Suppl 1):1098P. - Pratley RE, Kang J, Trautmann ME, et al. Body weight management and safety with efpeglenatide in adults without diabetes: A phase II randomised study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2019;21(11):2429-2439. doi:10.1111/dom.13824.

- Gerstein HC, Yang M, Lee SF, et al. Do non-glycaemic effects such as weight loss account for HbA1c lowering with efpeglenatide?: Insights from the AMPLITUDE-O trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2024;26(12):6080-6084. doi:10.1111/dom.15957.

- Lin D, Xiao H, Yang K, et al. Safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of TG103 injection in participants who are overweight or obese: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multiple-dose phase 1b study. BMC Med. 2024;22(1):209. doi:10.1186/s12916-024-03394-z.

- van der Velden WJC, Smit FX, Christiansen CB, et al. GLP-1 Val8: A biased GLP-1R agonist with altered binding kinetics and impaired release of pancreatic hormones in rats. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 2021;4(1):296-313. doi:10.1021/acsptsci.0c00193.

- Guo W, Xu Z, Zou H, et al. Discovery of ecnoglutide – a novel, long-acting, cAMP-biased glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) analog. Mol Metab. 2023;75:101762. doi:10.1016/j.molmet.2023.101762.

- Granhall C, Donsmark M, Blicher TM, et al. Safety and pharmacokinetics of single and multiple ascending doses of the novel oral human GLP-1 analogue, oral semaglutide, in healthy subjects and subjects with type 2 diabetes. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2019;58(6):781-791. doi:10.1007/s40262-018-0728-4.

- Buckley ST, Bækdal TA, Vegge A, et al. Transcellular stomach absorption of a derivatised glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10(467):eaar7047. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aar7047.

- Knop FK, Aroda VR, do Vale RD, et al. Oral semaglutide 50mg taken once per day in adults with overweight or obesity (OASIS 1): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2023;402(10403):705-719. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01185-6.

- Kawai T, Sun B, Yoshino H, et al. Structural basis for GLP-1 receptor activation by LY3502970, an orally active nonpeptide agonist. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117(47):29959-29967. doi:10.1073/pnas.2014879117.

- Griffith DA, Edmonds DJ, Fortin JP, et al. A small-molecule oral agonist of the human glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor. J Med Chem. 2022;65(12):8208-8226. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c01856.

- Buckeridge C, Cobain S, Bays HE, et al. Efficacy and safety of danuglipron (PF-06882961) in adults with obesity: A randomised, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging phase 2b study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2025;27(9):4915-4926. doi:10.1111/dom.16534.

- Stewart J. Danuglipron FDA approval status. Available at: www.drugs.com/history/danuglipron.html.

- Jastreboff AM, Aronne LJ, Ahmad NN, et al. Tirzepatide once weekly for the treatment of obesity. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(3):205-216. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2206038.

- Wadden TA, Chao AM, Machineni S, et al. Tirzepatide after intensive lifestyle intervention in adults with overweight or obesity: The SURMOUNT-3 phase 3 trial. Nat Med. 2023;29(11):2909-2918. doi:10.1038/s41591-023-02597-w.

- Aronne LJ, Sattar N, Horn DB, et al. Continued treatment with tirzepatide for maintenance of weight reduction in adults with obesity: The SURMOUNT-4 randomised clinical trial. JAMA. 2024;331(1):38-48. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.24945

- Aronne LJ, Horn DB, le Roux CW, et al. Tirzepatide as compared with semaglutide for the treatment of obesity. N Engl J Med. 2025;393(1):26-36. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2416394.

- Irwin N, McClean PL, O’ Harte FP, et al. Early administration of the glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide receptor antagonist (Pro3) GIP prevents the development of diabetes and related metabolic abnormalities associated with genetically inherited obesity in ob/ob mice. Diabetologia. 2007;50(7):1532-1540. doi:10.1007/s00125-007-0692-2.

- Lafferty RA, Flatt PR, Irwin N. GLP-1/GIP analogues: Potential impact in the landscape of obesity pharmacotherapy. Expert Opinion in Pharmacotherapies. 2023;24(5):587-597.

- Killion EA, Chen M, Falsey JR, et al. Chronic glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide receptor (GIPR) agonism desensitises adipocyte GIPR activity mimicking functional GIPR antagonism. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):4981. Published 2020 Oct 5. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-18751-8.

- Lafferty RA, Flatt PR, Gault VA,

Irwin N. Does glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide receptor blockade as well as agonism have a role to play in management of obesity and diabetes? J Endocrinol. 2024;262(2):e230339. doi:10.1530/JOE-23-0339. - Véniant MM, Lu SC, Atangan L, et al. A GIPR antagonist conjugated to GLP-1 analogues promotes weight loss with improved metabolic parameters in preclinical and phase 1 settings. Nat Metab. 2024;6(2):290-303. doi:10.1038/s42255-023-00966-w.

- Jastreboff AM, Ryan DH, Bays HE, et al. Once-monthly maridebart cafraglutide for the treatment of obesity – a phase 2 trial. N Engl J Med. 2025;393(9):843-857. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2504214.

- Gasbjerg LS, Hartmann B, Christensen MB, et al. GIP’s effect on bone metabolism is reduced by the selective GIP receptor antagonist GIP(3-30)NH2. Bone. 2020;130:115079. doi:10.1016/j.bone.2019.115079.

- Sánchez-Garrido MA, Brandt SJ, Clemmensen C, et al. GLP-1/glucagon receptor co-agonism for treatment of obesity. Diabetologia. 2017;60(10):1851-1861. doi:10.1007/s00125-017-4354-8.

- Shirley M. Mazdutide: First approval. Drugs. Published online September 30, 2025. doi:10.1007/s40265-025-02249-y.

- Zimmermann T, Thomas L, Baader-Pagler T, et al. 723-P: The dual glucagon and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor (GCGR/GLP-1R) agonist BI 4569 reduces body weight in diet-induced obese mice based on food intake reduction and an increase in energy expenditure. Diabetes. 2022;71(Supplement_1):23P.

- le Roux CW, Steen O, Lucas KJ, et al. Glucagon and GLP-1 receptor dual agonist survodutide for obesity: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-finding phase 2 trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2024;12(3):162-173. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(23)00356-X.

- Gault VA, Bhat VK, Irwin N, Flatt PR. A novel glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1)/glucagon hybrid peptide with triple-acting agonist activity at glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide, GLP-1, and glucagon receptors and therapeutic potential in high fat-fed mice. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(49):35581-35591. doi:10.1074/jbc.M113.512046.

- Coskun T, Urva S, Roell WC, et al. LY3437943, a novel triple glucagon, GIP, and GLP-1 receptor agonist for glycaemic control and weight loss: From discovery to clinical proof of concept. Cell Metab. 2022;34(9):1234-1247.e9. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2022.07.013.

- Jastreboff AM, Kaplan LM, Frías JP, et al. Triple-hormone-receptor agonist retatrutide for obesity – a phase 2 trial. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(6):514-526. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2301972.

- Boyle CN, Zheng Y, Lutz TA. Mediators of amylin action in metabolic control. J Clin Med. 2022;11(8):2207. Published 2022 Apr 15. doi:10.3390/jcm11082207.

- Enebo LB, Berthelsen KK, Kankam M, et al. Safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of concomitant administration of multiple doses of cagrilintide with semaglutide 2.4mg for weight management: A randomised, controlled, phase 1b trial. Lancet. 2021;397(10286):1736-1748. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00845-X.

- Davies MJ, Bajaj HS, Broholm C, et al. Cagrilintide-semaglutide in adults with overweight or obesity and type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2025;393(7):648-659. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2502082.

- Garvey WT, Blüher M, Osorto Contreras CK, et al. Co-administered cagrilintide and semaglutide in adults with overweight or obesity. N Engl J Med. 2025;393(7):635-647. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2502081.

- Hussain A, Farzam K. Setmelanotide. [Updated 2023 Jul 2]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Available at: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK589641/.

- Neeland IJ, Linge J, Birkenfeld AL. Changes in lean body mass with glucagon-like peptide-1-based therapies and mitigation strategies. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2024;26 Suppl 4:16-27. doi:10.1111/dom.15728.

- Han HQ, Zhou X, Mitch WE, Goldberg AL. Myostatin/activin pathway antagonism: Molecular basis and therapeutic potential. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 2013;45(10):2333-2347.

- Heymsfield SB, Coleman LA, Miller R, et al. Effect of bimagrumab vs placebo on body fat mass among adults with type 2 diabetes and obesity: A phase 2 randomised clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(1):e2033457. Published 2021 Jan 4. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.33457.

- Press release Regeneron. Interim results from ongoing phase 2 COURAGE trial confirm potential to improve the quality of semaglutide (GLP-1 receptor agonist)-induced weight loss by preserving lean mass. June 2025. Available at: https://newsroom.regeneron.com/news-releases/news-release-details/interim-results-ongoing-phase-2-courage-trial-confirm-potential.