Reference: August 2025 | Issue 8 | Vol 11 | Page 53

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a monogenic, inherited haemoglobinopathy that results in multisystem complications due to chronic haemolysis, vaso-occlusion, and inflammatory endothelial dysfunction. It is most prevalent in people of African or Caribbean background. The disease poses a significant global health burden and affects approximately 20-25 million individuals globally, with an estimated 300,000 infants born annually with the condition, a figure projected to rise due to demographic growth in high-prevalence regions such as sub-Saharan Africa and India.1,2,3

In some high-income countries, improved neonatal screening and comprehensive care programmes have extended life expectancy for those with SCD, but morbidity remains significant.

The condition arises from a single point mutation in the β-globin gene, resulting in the substitution of valine for glutamic acid at position six of the haemoglobin molecule, forming haemoglobin S (HbS).1,2,3

SCD is classified as rare within the EU. The 2017 EU Rare Diseases Plan established 24 European Reference Networks (ERNs), including ERN-EuroBloodNet, which is focused on rare haematological conditions. This initiative enhanced collaboration across member states and identified unmet needs in care provision, aiming to improve the management and treatment of individuals with rare diseases, including SCD.4

While the patient population in Ireland remains relatively low, at an estimated 600 people, the prevalence of SCD is rapidly growing here due to migration patterns.

Pathophysiology

SCD is an autosomal recessive haemoglobinopathy. The clinical hallmark is a triad of painful vaso-occlusion, micro-infarct end organ damage, and a haemolytic anaemia.

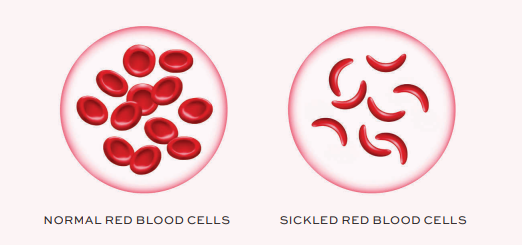

Under hypoxic, acidic, or dehydrated conditions, the mutant HbS undergoes a structural change that promotes polymerisation of the deoxygenated HbS tetramers. This polymerisation forms long, rigid intracellular fibres that distort the normal biconcave erythrocyte into the characteristic sickle shape. The sickling process is initially reversible; however, with repeated cycles of deoxygenation and reoxygenation, red blood cells (RBCs) become permanently deformed and lose membrane flexibility.1,5

These distorted erythrocytes are rigid, poorly deformable, and more adhesive to the vascular endothelium and to each other. Their impaired deformability hinders passage through the microcirculation, leading to vascular occlusion, tissue hypoperfusion, and local ischaemia. These events precipitate painful vaso-occlusive crises and underlie many of the acute and chronic complications associated with the disease.5,6,7

Sickled cells have a shortened lifespan, with an average survival of only 10-20 days compared to the normal 120 days for healthy RBCs. This accelerated destruction leads to chronic haemolytic anaemia. Intravascular haemolysis results in the release of cell-free haemoglobin into the plasma, which rapidly binds to and depletes nitric oxide (NO), a critical vasodilator. The resultant NO scavenging contributes to vasoconstriction, endothelial dysfunction, and platelet activation, creating a pro-inflammatory and prothrombotic vascular environment.5,6,7

Haemolysis frees arginase-1 and other erythrocyte-derived molecules that exacerbate NO depletion and promote oxidative stress. The exposed phosphatidylserine on the outer membrane of sickled RBCs enhances their clearance by macrophages and supports a hypercoagulable state. Concurrently, leukocytes, particularly neutrophils, become activated and adhere to the endothelium, secreting pro-inflammatory cytokines and generating reactive oxygen species that amplify vascular injury.5,6,7

Endothelial cells respond to this by upregulating adhesion molecules such as VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and E-selectin, which further facilitate the entrapment of sickled erythrocytes, platelets, and leukocytes. This adhesive interaction is central to the pathogenesis of vaso-occlusion. The cumulative effect is a cyclical cascade of hypoxia, inflammation, endothelial activation, and microvascular occlusion that leads to ischaemia-reperfusion injury and promotes progressive damage to vital organs.5,6,7

Over time, these pathophysiological processes culminate in multisystem organ dysfunction. In the lungs, recurrent infarction and inflammation contribute to the development of pulmonary hypertension and acute chest syndrome. The brain is highly susceptible to both overt stroke and silent cerebral infarction, particularly in children.

Chronic renal injury develops from persistent hypoperfusion and glomerular hyperfiltration, while avascular necrosis occurs in bones due to repeated ischaemic insults. In the eyes, proliferative sickle retinopathy can result in visual impairment or blindness. The spleen is often rendered non-functional early in life due to repeated infarctions, leaving individuals highly susceptible to infections.5,6,7

Clinical presentation

SCD is typically asymptomatic in early infancy, with manifestations emerging as foetal haemoglobin levels decline.1 Over time, a variety of factors influence the severity and type of symptoms. Common features of the disease include haemolytic anaemia, chronic low-level pain, and intermittent vaso-occlusive crises, often causing pain in bones and joints.

Other complications include hand-foot syndrome, acute chest syndrome, splenic sequestration, vision loss, growth retardation, leg ulcers, deep vein thrombosis, and organ damage, particularly to the liver and bones.2,3,6,7

Cardiac, renal, and hepatic disorders, along with gallstones, priapism and, notably, stroke are also prevalent. Children with SCD are at risk of asymptomatic strokes, ischaemic stroke, sino-venous thrombosis, posterior leukoencephalopathy, and acute demyelination, which can lead to additional complications, such as seizures, learning difficulties, physical disabilities, and coma. Painful crises caused by vaso-occlusion and bone infarction are common, with dactylitis (painful swelling of fingers or toes) seen in infants.1,2,3,6,7

Long-term complications include avascular necrosis of bones, especially at the heads of long bones, leading to joint damage. Osteopenia and osteoporosis can contribute to vertebral collapse and chronic back pain. Factors such as higher haematocrit levels and the presence of ∂-thalassaemia trait have been linked to an increased risk of bone infarctions, although the data remains inconclusive.

Among the most frequent morbidities related to SCD are pain crises, cerebrovascular accidents, and dysfunction of the spleen and kidneys.1,2,3,6,7

Acute chest syndrome is the most common cause of hospitalisation for patients with SCD, with a peak incidence in early childhood, and is responsible for approximately 25 per cent of sickle-related deaths.

Diagnosis

SCD can be diagnosed in utero or in the newborn period by screening, or be detected at any time during life. Diagnosis of SCD is established through haemoglobin electrophoresis or high-performance liquid chromatography, with confirmation by genetic testing if necessary.

Newborn screening programmes are established in some high-income countries, allowing for early diagnosis and the initiation of prophylactic measures such as penicillin prophylaxis and vaccination against Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae. In low-resource settings, however, diagnostic infrastructure is often lacking, resulting in delayed identification and increased early mortality.1,2,7

SCD is not currently part of the national newborn screening programme. However, there are calls to expand the screening programme to include SCD, as it is part of newborn screening in other European countries. Targeted screening is available in Ireland for babies at increased risk based on their family history, and blood tests in pregnancy should be offered for those who may be at risk.8

Management

Treatment goals primarily focus on preventing and managing symptoms (pain) and complications.1,2,9 Timely identification and intervention are important to minimise disease-related morbidity and pain. This includes regular monitoring, such as transcranial Doppler (TCD) ultrasounds in children to assess stroke risk, facilitate early detection and management of pulmonary hypertension, and monitor for organ dysfunction commonly associated with the disease.3,7,10

Most patients will experience vaso-occlusive events at some point in their lives and these episodes account for the vast majority of emergency hospital admissions. They can lead to acute organ failure or chronic organ damage affecting all systems.

A range of disease-modifying therapies are available to reduce the frequency and severity of complications. Hydroxyurea remains a cornerstone of treatment. It functions by increasing levels of foetal haemoglobin, thereby reducing red cell sickling and haemolysis.

Additionally, hydroxyurea lowers circulating leukocyte counts, which helps reduce inflammation and vascular adhesion events. Other treatments include crizanlizumab, a P-selectin inhibitor that mitigates vaso-occlusion by reducing cellular adhesion, and voxelotor, a HbS polymerisation inhibitor that stabilises haemoglobin in its oxygenated form, thereby improving haemoglobin levels by reducing haemolysis.2,3 7,9,10

Supportive multidisciplinary care continues to play a vital role in managing acute complications and preventing long-term sequelae. This includes blood transfusion therapy for stroke prevention and acute anaemia, iron chelation for transfusional siderosis. As blood transfusion therapy is of benefit in both the acute management of vaso-occlusive events and chronic management to prevent micro-infarct end organ damage, most patients with sickle cell disease will undergo numerous transfusions in their lifetime. Comprehensive care models are important to optimise outcomes.2,3,7

Emerging therapies

Ongoing clinical trials are evaluating newer agents aimed at targeting the underlying pathophysiology of the disease through diverse mechanisms. These include agents that reduce HbS polymerisation, such as pan-histone deacetylase inhibitors, and DNMT1 inhibitors.

Therapies targeting oxidative stress and inflammation are also under investigation. For example, carbon monoxide-releasing molecules aim to improve oxygen delivery, while phosphodiesterase-9 inhibitors are being explored for their potential to raise foetal haemoglobin levels.7

Investigational agents include poloxamer and vepoloxamer, which are surfactants designed to prevent red cell adhesion and improve blood flow, thus reducing vaso-occlusion. Inflammatory pathways are another focus, with therapies being tested to inhibit platelet activation, modulate immune response, or target endothelial dysfunction.

Anticoagulants, like rivaroxaban, and antioxidants, such as N-acetylcysteine, are also under evaluation for their roles in minimising thrombosis and oxidative injury, respectively.7,10

This multifaceted therapeutic approach highlights the complexity of SCD and the importance of individualised treatment plans that address both acute complications and long-term disease progression. While these agents represent important additions to the therapeutic arsenal, their cost and limited long-term data remain barriers to widespread adoption.

Curative therapies

Allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) remains the only established curative therapy for SCD. Outcomes are most favourable in children with matched sibling donors, with event-free survival rates exceeding 90 per cent. However, only a minority of patients have access to a suitable donor. Advances in haploidentical transplantation and the use of reduced-intensity conditioning regimens are expanding the potential candidate pool.10

Gene therapy has emerged as a transformative frontier in treatment. Recent approaches include lentiviral vector-mediated addition of anti-sickling β-globin genes and gene editing strategies to reactivate foetal haemoglobin production. A 2021 study reported the successful application of CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing in a small cohort of patients with SCD and β-thalassaemia, resulting in transfusion independence and resolution of vaso-occlusive crises.

The subsequent US FDA approval of exagamglogene autotemcel in 2023 marked the first approved CRISPR-based gene therapy for SCD, setting a new precedent in precision medicine. While these advances are ground-breaking, long-term safety data and equitable access are key considerations.11,12

Psychosocial impact

SCD has profound social and psychological impacts on affected individuals and their families, with a sense of stigma and fear still common. Managing the disease and its complications can be particularly challenging for patients, caregivers, and healthcare providers.

The unpredictable nature of SCD, including recurrent pain, hospitalisations, and complications, contributes to emotional distress, anxiety, and difficulty coping. Daily life is often disrupted due to physical limitations, treatment regimens, and the unpredictability of disease-related events. These challenges can lead to reduced participation in educational, occupational, and social activities, significantly affecting quality of life.1,2,3,9

Neurocognitive impairments, in combination with the physical symptoms of the disease, may hinder the individual’s functional abilities. Psychological distress is common and requires ongoing support. A comprehensive care approach is important, especially during hospital admissions or periods of crisis. Disruptions in schooling during key developmental stages can affect academic progress and social development, while the burden of care may place strain on family relationships and routines.1,2,3,9

The psychosocial burden of SCD extends to employment and personal independence in adulthood, often limiting career opportunities and affecting economic stability. Adapting psychologically to living with SCD depends on several factors, including family dynamics, social support systems, community inclusion, personality traits, and access to care and information. For individuals from minority backgrounds, additional social and systemic challenges may further complicate adjustment.1,2,3,9

Psychosocial support, disease education, emotional counselling, and opportunities for peer interaction can all play vital roles in helping individuals with SCD cope more effectively. Encouragement, reassurance, and structured interventions tailored to the patient’s environment and life stage can significantly enhance psychological resilience and overall well-being.1,2,3,9

In 2021, a UK All-Parliamentary Group on Sickle Cell and Thalassaemia published a report which highlighted that “awareness of sickle cell among healthcare professionals is low, with sickle cell patients regularly having to educate healthcare professionals about the basics of their condition at times of significant pain and distress”.13

Specialised service

St James’s Hospital Dublin, has a specialised service for SCD and thalassaemia, also referred to as the haemoglobinopathy service. The service is available to adult patients diagnosed with SCD or thalassaemia, referred by their GP, consultant, or through a transition clinic.

The primary goal is to offer specialised medical care, and provide support and advice to patients regarding their physical and social needs. A weekly outpatient clinic is available, with daily treatments provided in the day ward.14

The service works in close partnership with Our Lady’s Children’s Hospital, Crumlin (OLCHC), which offers specialised care for children with SCD and thalassaemia in Ireland. When young patients reach the age of 16 to 18, their care is transferred to the adult service. This transition is supported by a monthly clinic at OLCHC, giving young people the chance to meet the adult care team. The clinic also helps them to begin taking more responsibility for managing their condition as they move into adult life.14

Conclusion

SCD is a complex, systemic disorder, which can place a substantial medical, social, and financial burden on patients, their families and their carers. Although survival rates have improved with comprehensive care and therapy, disease-related complications continue to impact quality of life and functional outcomes.

The development of novel agents targeting specific molecular pathways and the introduction of gene therapy mark a paradigm shift in the management of SCD. Future efforts should focus on improving global access to existing therapies, ensuring safe and equitable deployment of curative treatments, and addressing the psychosocial dimensions of care.

References

- Mangla A, Agarwal N, Maruvada S. Sickle Cell Anaemia. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Available at: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482164/.

- Kavanagh L, Fasipe T, Wun T. Sickle cell disease: A review. JAMA. 2022 Jul 5;328(1):57-68.

- O’Brien E, Ali S, Chevassut T. Sickle cell disease: An update. Clin Med (Lond). 2022;22(3):218-20.

- Mañú Pereira M, Colombatti R, Alvarez F, Bartolucci P, Bento C, Brunetta A, et al. Sickle cell disease landscape and challenges in the EU: The ERN-EuroBloodNet perspective. Lancet Haematol. 2023;10(8): e687-94.

- Sundd P, Gladwin M, Novelli E. Pathophysiology of sickle cell disease. Annu Rev Pathol. 2019; 14:263-92.

- Inusa B, Hsu L, Kohli N, Patel A, Ominu-Evbota K, Anie K, Atoyebi, W. Sickle cell disease – genetics, pathophysiology, clinical presentation and treatment. Int J Neonatal Screen. 2019; 5(2), p20.

- Tebbi C. Sickle cell disease: A review. Haemato. 2022;3(2):341-66.

- Health Service Executive (HSE). Blood tests offered in pregnancy. Health Service Executive; 2023. Available at: www2.hse.ie/pregnancy-birth/scans-tests/blood-tests/blood-tests-offered/.

- Spurway A, George S, Thompson C, Weeks S. Sickle cell disease: Causes, treatments, and the patient experience. Pharm J. 2024 Jan 9.

- Brandow A, Liem R. Advances in the diagnosis and treatment of sickle cell disease. J Haematol Oncol. 2022; 15:20.

- Frangoul H, Altshuler D, Cappellini M, et al. CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing for sickle cell disease and β-thalassaemia. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(3):252-260.

- Ledford H. CRISPR gene therapy shows promise against blood diseases. Nature. 2020 Dec;588(7838):383.

- UK All-Parliamentary Group on Sickle Cell and Thalassaemia. No one’s listening: An inquiry into the avoidable deaths and failures of care for sickle cell patients in secondary care. 2019. Available at: www.sicklecellsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/No-Ones-Listening-Final.pdf.

- St James’s Hospital Dublin. (2025). Sickle Cell and Thalassaemia. Available at: www.stjames.ie/services/hope/sicklecellandthalassaemia/.