Reference: September 2025 | Issue 9 | Vol 11 | Page 30

How to optimise care for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), from management to complications, was the focus of a dedicated two-speaker session during the Irish Society of Gastroenterology (ISG) Winter Meeting in November 2024.

Prof Johan Burisch, Consultant Gastroenterologist at Copenhagen University Hospital, Hvidovre, Denmark, gave a detailed presentation on the management of ulcerative colitis (UC) flare in patients with mild to moderate disease.

During his talk, Prof Burisch emphasised the need to “get the most out of established treatments for UC before we move on to newer therapies”, focusing on the use of 5-aminosalicylate (5-ASA) therapy specifically.

He outlined evidence-based strategies to consider for optimisation of 5-ASA therapy in UC patients, with key elements including individual dosing, treatment duration, adherence, and topical therapy.1

Dose optimisation

“Of course, the first thing is to choose the right dose for the right patient,” Prof Burisch said, citing a 2019 American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) technical review of data on different induction doses of 5-ASA (≥2g vs <2g) and the induction of remission.2

“What it shows basically is if you choose any dose above 2g, this is better than choosing low-dose mesalazine. It is also what is summarised in most guidelines around the world.”

Furthermore, doses over 3g have also been shown to have superior efficacy compared to low doses (<2g).2 Prof Burisch cited further data from the review, which showed mesalazine doses over 3g/day (relative risk (RR) 0.81; 95% confidence intervals (CI) 95 0.71-0.92) and 2-3g/day (RR 0.88; 95% CI 0.79-0.99) were superior to doses of less than 2g/day of mesalazine for induction of remission, with low heterogeneity.*

He then cited data from the randomised, double-blind, controlled ASCEND II and ASCEND III trials which assessed the efficacy of 4.8g/day vs 2.4g/day of mesalazine in adults with active UC, confirming the efficacy of higher doses in different subgroups, including those who had tried other treatments.3,4

As well as optimising the initiation dosage, the right maintenance dose is also very important in 5-ASA treatment for UC, Prof Burisch said. The standard optimum dose for maintaining remission is between 2-3g/day of mesalazine, he said, quoting a systemic review and meta-analysis of trial data supporting this approach.5

He also quoted a Japanese study looking at 527 patients with UC who achieved remission on 4.8g/d 5-ASA treatment and what happened when they were switched to maintenance dosing (>3g/d vs <3g/d).6

“This is again something we need to consider when dealing with our patients. If it was difficult to get them into remission and we used higher doses, maybe we should keep them on higher doses for a longer time before going down in dosage,” he said, highlighting the importance of stratifying patients appropriately.

He quoted another study which showed a reduction in the risk of flares with high-dose mesalazine compared to low-dose mesalazine in UC patients with low adherence, “which is something we should consider in clinical practice when dealing with patients with low adherence”.7

Prof Burisch next discussed the role of topical therapy for induction of remission in UC and for the prevention of relapse.8,9

“Combination of topical and oral mesalazine for maintenance of remission is better than low-dose oral mesalazine, as has been shown in several studies,” he said, summarising the findings.

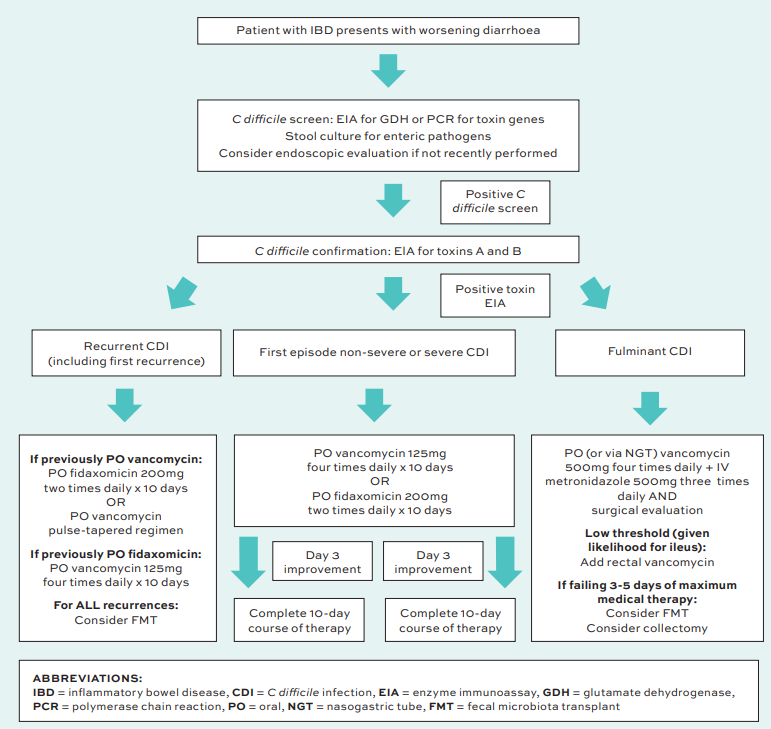

FIGURE 1: Comprehensive diagnostic and management algorithm of CDI in IBD. Adapted from Dalal RS, et al. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2021 Jul 1;37(4):336-343.

Adherence

Medication adherence is a key issue to ensuring the best outcomes for UC patients on 5-ASA therapy, Prof Burisch emphasised.

Research has shown that non-adherent patients have up to five times higher risk of relapse than those who take their medicine regularly, he said.10,11

Prof Burisch cited data which showed an overall 79 per cent rate of non-adherence with any 5-ASA after one year, with a substantial decrease in 5-ASA therapy adherence after just 30 days.12 “This is something all of us who see these patients are familiar with,” he remarked.

If patients are not taking their medication as prescribed, then drug effectiveness will obviously be impacted and the clinician may think it is not working for them and switch to another treatment unnecessarily, Prof Burisch stressed.

“We really need to address this issue. If you don’t address it and you do not have a good enough relationship with your patient where they feel comfortable enough to admit that they are not taking their medication, it makes it difficult to make the right decisions. You might move on [to a different medication] for the wrong reasons,” Prof Burisch said.

In this regard, research also confirms the importance of consulting with patients about drug formulation and dosage frequency preferences to try to maximise adherence, he said.13

“Trial data shows that those patients who have a good understanding of their disease and a good relationship with their physician have better adherence,” Prof Burisch stated.14

Clostridium difficile

Also at the ISG Winter Meeting, Dr Tee Keat Teoh, Consultant Microbiologist, Public Health Laboratory Dublin and St James’s Hospital, addressed the risk of Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) in IBD.

He reminded the meeting that CDI is the leading cause of hospital-acquired infectious diarrhoea in adults, and is associated with significant morbidity, mortality, and costs.15,16,17 CDI can lead to complications like severe colitis, toxic megacolon, and death.15

CDI normally develops in people who are already vulnerable, with key risk factors including previous antibiotic exposure, older age, a weakened immune system, recent hospital or nursing home admission, and previous history of CDI, Dr Teoh outlined.18

The literature shows that IBD patients have a five times increased risk of CDI compared to the general population. IBD patients also tend to do worse and have a significantly increased risk of recurrent CDI risk, especially in those aged below 50, he noted.19

Specifically, there is an increased incidence of CDI in UC, compared to Crohn’s disease.19 Colonic dysbiosis from colitis impairs resistance to bacterial colonisation, and immunosuppression may impair immune response to CDI,” he said, adding that about 8 per cent of IBD patients have asymptomatic toxigenic C difficile.20

Diagnosis of CDI in IBD patients is difficult, largely due to the symptom overlap of both conditions, and they also present differently (younger age, more often community onset, antibiotic exposure less likely), Dr Teoh said.19,21

Furthermore, CDI in IBD patients can lead to subsequent IBD flares, escalation of treatment, and poorer patient outcomes.21

Currently there is no international consensus guidance for specifically managing IBD patients with CDI, De Teoh explained.

General European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) guidance on managing CDI recommends fidaxomicin for first-line use in all patients with CDI, he noted.22 Metronidazole is no longer recommended as a first-line agent for CDI treatment by the aforementioned bodies in their latest guidance.

Dr Teoh also discussed the use of other treatments for CDI in IBD patients, including faecal microbiota transplant which, while shown to be safe and effective, is not yet easily accessible in Ireland.23

In relation to prescribing IBD immunosuppressives during CDI diagnosis, Dr Teoh noted that the literature is sparse but an AGA practice review says the decision should be individualised, but is positive towards continuation in uncomplicated CDI.21

Concluding his talk, Dr Teoh recommended using a detailed algorithm for the diagnosis and treatment of CDI in IBD, published in Current Opinion in Gastroenterology in 2021.19

*Not all mesalazine preparations are licensed for doses >3g/day for inducing remission. Please check individual product SmPCs.

References

- Taylor KM, Irving PM. Optimisation of conventional therapy in patients with IBD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011 Oct 4;8(11):646-56. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2011.172. PMID: 21970871.

- Ko CW, Singh S, Feuerstein JD, et al; American Gastroenterological Association Institute Clinical Guidelines Committee. AGA clinical practice guidelines on the management of mild to moderate ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2019 Feb;156(3):748-764. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.12.009. Epub 2018 Dec 18. PMID: 30576644.

- Hanauer SB, Sandborn WJ, Kornbluth A, et al. Delayed-release oral mesalamine at 4.8g/day (800mg tablet) for the treatment of moderately active ulcerative colitis: The ASCEND II trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005 Nov;100(11):2478-85. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00248.x. PMID: 16279903.

- Sandborn WJ, Regula J, Feagan BG, et al. Delayed-release oral mesalamine 4.8g/day (800mg tablet) is effective for patients with moderately active ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2009 Dec;137(6):1934-43.e1-3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.08.069. Epub 2009 Sep 18. PMID: 19766640.

- Nguyen NH, Fumery M, Dulai PS, et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of pharmacological agents for management of mild to moderate ulcerative colitis: A systematic review and network meta-analyses. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Nov;3(11):742-753. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(18)30231-0. Epub 2018 Aug 17. PMID: 30122356.

- Fukuda T, Naganuma M, Sugimoto S, et al. The risk factor of clinical relapse in ulcerative colitis patients with low dose 5-aminosalicylic acid as maintenance therapy: A report from the IBD registry. PLoS One. 2017 Nov 6;12(11):e0187737. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0187737. PMID: 29108025.

- Khan N, Abbas AM, Koleva YN, Bazzano LA. Long-term mesalamine maintenance in ulcerative colitis: Which is more important? Adherence or daily dose. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013 May;19(6):1123-9. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e318280b1b8. PMID: 23514878.

- Probert CS, Dignass AU, Lindgren S, Oudkerk Pool M, Marteau P. Combined oral and rectal mesalazine for the treatment of mild to moderately active ulcerative colitis: Rapid symptom resolution and improvements in quality of life. J Crohns Colitis. 2014 Mar;8(3):200-7. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.08.007. Epub 2013 Sep 4. PMID: 24012063.

- Barberio B, Segal JP, Quraishi MN, Black CJ, Savarino EV, Ford AC. Efficacy of oral, topical, or combined oral and topical 5-aminosalicylates, in ulcerative colitis: Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. J Crohns Colitis. 2021 Jul 5;15(7):1184-1196. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab010. PMID: 33433562.

- Kane S, Huo D, Aikens J, Hanauer S. Medication nonadherence and the outcomes of patients with quiescent ulcerative colitis. Am J Med. 2003 Jan;114(1):39-43. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01383-9. PMID: 12543288.

- Kane SV. Systematic review: Adherence issues in the treatment of ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006 Mar 1;23(5):577-85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02809.x. PMID: 16480396.

- Yen L, Wu J, Hodgkins PL, Cohen RD, Nichol MB. Medication use patterns and predictors of nonpersistence and nonadherence with oral 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy in patients with ulcerative colitis. J Manag Care Pharm. 2012 Nov-Dec;18(9):701-12. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2012.18.9.701. PMID: 23206213.

- Hébuterne X, Vavricka SR, Thorne HC, et al. Medication formulation preference of mild and moderate ulcerative colitis patients: A European survey. Inflamm Intest Dis. 2023 May 12;8(1):41-49. doi: 10.1159/000530139. PMID: 37711959.

- Dasharathy SS, Long MD, Lackner JM, et al. Psychological factors associated with adherence to oral treatment in ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2023 Jan 5;29(1):97-102. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izac051. PMID: 35325148.

- Vindigni SM, Surawicz CM. Clostridioides difficile infection: Changing epidemiology and management paradigms. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2015 Jul 9;6(7):e99. doi: 10.1038/ctg.2015.24. PMID: 26158611.

- Boven A, Vlieghe E, Engstrand L, et al. Clostridioides difficile infection-associated cause-specific and all-cause mortality: A population-based cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2023 Nov;29(11):1424-1430. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2023.07.008. Epub 2023 Jul 19. PMID: 37473840.

- Yu H, Alfred T, Nguyen JL, Zhou J, Olsen MA. Incidence, attributable mortality, and healthcare and out-of-pocket costs of Clostridioides difficile infection in US Medicare Advantage Enrollees. Clin Infect Dis. 2023 Feb 8;76(3):e1476-e1483. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciac467. PMID: 35686435.

- 18 Gould CV, File TM Jr, McDonald LC. Causes, burden, and prevention of Clostridium difficile infection. Infect Dis Clin Pract (Baltim Md). 2015 May;23(6):281-288. doi: 10.1097/IPC.0000000000000331. PMID: 31048951.

- Dalal RS, Allegretti JR. Diagnosis and management of Clostridioides difficile infection in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2021 Jul 1;37(4):336-343. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0000000000000739. PMID: 33654015.

- Micic D, Yarur A, Gonsalves A, et al. Risk factors for Clostridium difficile isolation in inflammatory bowel disease: A prospective study. Dig Dis Sci. 2018 Apr;63(4):1016-1024. doi: 10.1007/s10620-018-4941-7. Epub 2018 Feb 8. Erratum in: Dig Dis Sci. 2018 Oct;63(10):2815. doi: 10.1007/s10620-018-5249-3. PMID: 29417331.

- Khanna S, Shin A, Kelly CP. Management of Clostridium difficile infection in inflammatory bowel disease: Expert review from the Clinical Practice Updates Committee of the AGA Institute. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017 Feb;15(2):166-174. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.10.024. Erratum in: Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017 Apr;15(4):607. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.01.023. PMID: 28093134.

- van Prehn J, Reigadas E, Vogelzang EH, et al; Guideline Committee of the European Study Group on Clostridioides difficile. European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases: 2021 update on the treatment guidance document for Clostridioides difficile infection in adults. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021 Dec;27 Suppl 2:S1-S21. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.09.038. Epub 2021 Oct 20. PMID: 34678515.

- van Nood E, Vrieze A, Nieuwdorp M, et al. Duodenal infusion of donor feces for recurrent Clostridium difficile. N Engl J Med. 2013 Jan 31;368(5):407-15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1205037. Epub 2013 Jan 16. PMID: 23323867.