Director of the HSE Global Health Programme Prof David Weakliam talks to Niamh Cahill about the importance of global healthcare and establishing meaningful collaborations with lower income countries

Prof David Weakliam, Director of the HSE Global Health Programme, first visited Africa over 40 years ago. In the decades since, global health has been an enduring feature of his career.

After studying medicine in Ireland, he initially trained as a GP. However, his growing interest in public health medicine ultimately led him to pursue a career in the specialty.

Several years were spent working in Africa and Asia before the now Adjunct Professor at University College Dublin settled back in Ireland.

On his return in 2003, he joined the Department of Foreign Affairs with Irish Aid, the Government’s overseas aid programme, where he served as a health advisor.

In 2007, Prof Weakliam was recruited to the HSE, playing a key role in establishing the Global Health Programme, launched in 2010.

The Programme emerged from an agreement between the HSE and Irish Aid, enabling the HSE both to support the group’s work in low- and middle-income countries and to strengthen its own global engagement.

“Health is very global,” Prof Weakliam told the Medical Independent (MI).

“Any health issue that we face in Ireland these days really has a global dimension and global connection. For anyone working in the health service, there’s a value in understanding health in a global way.”

For anyone working in the health service, there’s a value in understanding health in a global way

The Covid-19 pandemic, he observed, underscored the extent to which health issues in one country affect others.

“I think we now very much appreciate, after the Covid pandemic, how much countries are interconnected when it comes to health,” he said.

Over the past 15 years, the Global Health Programme has steadily evolved and expanded. Prof Weakliam was its sole staff member until 2020; today, it has grown to a team of four.

Funded through Irish Aid via the Department of Foreign Affairs, as well as the Department of Health, the Programme supports work in low- and middle-income countries and in crisis settings, such as Ukraine, with a focus on strengthening health services and improving health outcomes.

Collaboration is at the heart of all its work, Prof Weakliam emphasised. This approach is reflected in partnerships with countries such as Ethiopia, Mozambique, Sudan, Tanzania, and Zambia.

“We respond when other countries request our assistance and we then build up links with those countries to understand what their needs are and find out from them what they would like us to contribute to,” he explained.

“The old model of aid was that ‘we were the experts and we provide help to other countries’. That’s not the way we work anymore. We work as partners. Each country has its challenges and problems and we work together in a shared, equal way to learn from each other.”

Each country has its challenges and problems, and we work together in a shared, equal way to learn from each other

Prof Weakliam said the Global Health Programme’s focus is often on lower income countries “because their health needs are very great”.

“[But] our approach is very much in terms of equality and a two-way exchange – what we can learn in Ireland as well as what we contribute. There is no doubt that we learn so much working with other countries.”

Mozambique

During a recent visit to Mozambique, Prof Weakliam and the Programme marked the 10-year anniversary of partnership with the nation.

“It’s very nice to see what’s been accomplished over the years,” Prof Weakliam told MI.

“I met the Health Minister there and he is keen to continue the collaboration. It was good to get strong endorsement from their side that they wanted to continue the partnership.”

Mozambique was among the Global Health Programme’s earliest partners.

The collaboration began when Mozambique’s Ministry of Health highlighted major challenges in the quality and safety of hospital care – areas it has since worked to improve with Ireland’s support.

Together with the Global Health Programme, they developed a training initiative with Irish clinicians travelling to Mozambique to support hospital staff. Teams there gained skills in quality improvement, from identifying and analysing problems and implementing practical measures to address them.

Mozambique has shortages of staff and equipment in its hospitals, but addressing those deficits was not the objective of the initiative.

“We believe there is a lot staff can do themselves in their way of working,” Prof Weakliam said.

“Each hospital identified a particular challenge they faced around quality and they worked on that using the training that we provided with the Ministry of Health.”

A wide range of problems were identified across hospitals, including high patient mortality rates after admission, elevated maternal deaths, long waiting times in emergency departments, delays for gynaecology outpatient appointments, and poor communication with patients.

The initiative helped to provide practical skills and learning, which has resulted in real improvements in care, according to Prof Weakliam.

“To give an example, one hospital was recording on average 11 deaths per month on their medical ward within 24 hours of admission,” he said.

“At the end of their training, and the project they implemented, they had reduced that to four a month. This was in 2017. Subsequently they saw a reduction from 58 deaths in a year in 2017 to eight deaths in 2019.”

Prof Weakliam said on his recent visit it was “very satisfying” to “see they are still sustaining those ongoing and continued benefits”.

He added that staff there continue to implement measures on an ongoing basis. The Global Health Programme visits once a year to provide further coaching and training. Online training and coaching are also provided.

“In one hospital, when we visited last week, we saw they have established a whole department for improving quality of care, with staff assigned to work across the hospital improving care with quality coordinators,” Prof Weakliam said.

About 18 hospitals in Mozambique are now involved in the initiative.

In many cases, hospitals can demonstrate measurable improvements in patient care, from shorter waiting times to reduced mortality.

Maternal health

There is currently a concentrated focus in Mozambique on reducing maternal deaths, as the country has a very high maternal mortality rate.

In just one large hospital in Maputo, the capital, 38 maternal deaths were reported last year, according to Prof Weakliam.

“The work that we’re doing with them will be to provide more training and support them to tackle that problem, which is solvable without them having to get lots of extra resources, if they can improve the way they provide care,” he explained.

Prof Weakliam highlighted the importance of the partogram in maternal health. This graphical tool is used during labour and delivery to track the progress of childbirth and monitor the wellbeing of both mother and baby.

“What’s important is that in doing this they are identifying women at risk of developing complications that could be serious and that allows them to intervene and take measures to prevent deaths.”

In the north of the country, in Niassa province, a project has been launched to reduce maternal mortality.

According to Prof Weakliam, all women in the project receive partogram monitoring and early results indicate a significant reduction in maternal deaths.

Despite Mozambique being a poor country with scarce resources, Prof Weakliam believes many problems in hospitals can be addressed through training and advice.

“It’s a very effective model because it doesn’t cost a lot when you look at all the potential benefits and lives saved. It’s a very small cost. It’s efficient and it’s sustainable. That’s the key thing for us – when improvements happen, that they are sustained.”

Zambia

In Zambia, the Global Health Programme works as part of the EQUALS Initiative with the RCPI. This is a joint initiative that seeks to improve healthcare and address healthcare inequalities by providing equipment and training.

The initiative commenced with Zambia, but has since been extended to Uganda and Ukraine. It began in response to a request from Zambia for medical equipment. Since 2014, the HSE has been sending containers of reusable medical equipment to Zambia every year.

“This is equipment that’s being replaced in our health service under our national equipment replacement programme that is no longer going to be used in Ireland and would otherwise be discarded or go back to the companies. We make that available for donation and we have been donating to Zambia for over 10 years now,” Prof Weakliam said.

Biomedical engineers working with Irish hospitals support training of engineers in Zambia to enable them to maintain the equipment, he added.

It was through this process that Prof Weakliam learned about efforts to develop a specialist postgraduate medical training programme for doctors in Zambia.

“What has been happening historically in Zambia, like most of Africa, is doctors leave the country in order to get their specialist training because it’s not available in their own country. But with that comes a brain drain and they [often] don’t go back,” Prof Weakliam said.

In 2017, Zambia established the Zambian College of Medicine and Surgery and through the EQUALS Initiative they requested support to develop a training programme.

“So, with our experience working with the RCPI, who have developed world-class training programmes in Ireland, we’ve been in a position to give them advice about how they might go about setting up a training programme,” he said.

“I was in Zambia in June for a graduation of the latest batch of doctors and this year they will have reached 388 specialists trained in 16 specialties. That’s an amazing achievement.

“We enabled them to put that programme in place. Last year we supported them with a small amount of funding and then with advice to develop their strategic plan for their training for the next five years. We tailor our support to what they request and need at a particular time.”

Crises

The Global Health Programme has responded and continues to respond to requests from countries for assistance in times of crises.

During the Covid pandemic, it facilitated the donation of Covid-related medical equipment to India and Nepal when they were experiencing high rates of Covid cases and when Ireland’s peak had passed.

“We had purchased a lot of equipment in the event that it might be needed and when it was identified that there was equipment no longer needed, we were able to donate that to countries like India and Nepal.

“Since then, we have been responding at the request of other Government departments to crisis situations like the conflict in Ukraine and Sudan and we’ve been donating medical equipment to those two countries.”

In Ukraine, the Global Health Programme works with non-governmental organisations to help deliver medical equipment.

It also provides advice and supports the distribution of funding for the University College Dublin Ukraine Trauma Project, Prof Weakliam said.

“The project aims to provide emergency resuscitation training for a range of personnel working in conflict areas, but also for [civilians] to resuscitate people seriously injured and the funding for that is administered by our Programme,” Prof Weakliam stated.

In response to the crisis in Gaza, Ireland has brought sick children here for medical care; however, the Global Health Programme has not been directly involved in that aspect of support.

According to Prof Weakliam, the Programme has contributed in other ways.

“We have provisions within the HSE to release staff to work with other agencies for short-term assignments.”

He said that “under approved arrangements”, some staff have been deployed to countries near Gaza to provide specialist skills, such as epidemiology, as a result of the crisis.

Learning at home

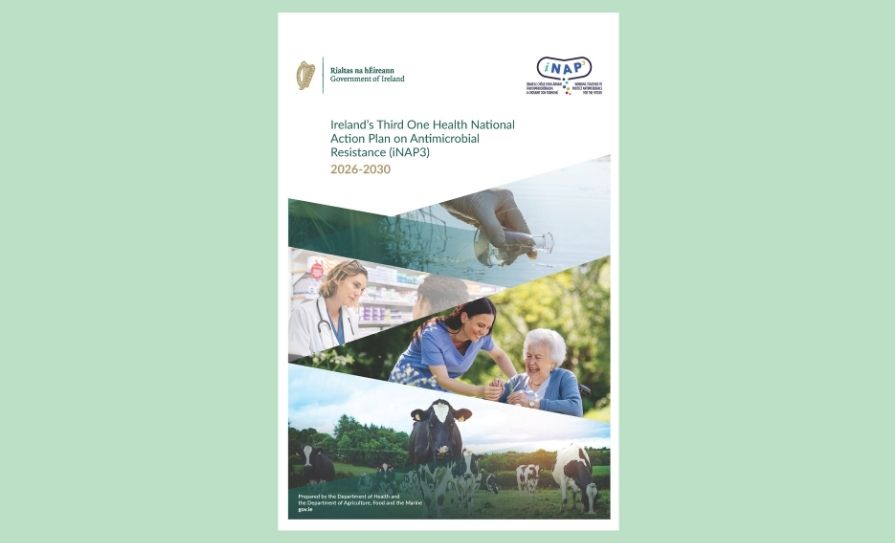

As Chair of the global health committee of the Forum of Irish Postgraduate Medical Training Bodies, Prof Weakliam has helped develop a global health curriculum that has been incorporated into specialist training programmes for doctors across all specialties.

The curriculum addresses topics including culture, epidemiology, diseases, climate change, sustainability, and health workforce and systems issues, highlighting the relevance of global health knowledge and skills for all health service workers.

It is also available as an e-learning module through the training bodies’ platforms, allowing doctors to further develop their expertise in the area.

In addition to his work on the curriculum, Prof Weakliam serves on committees such as the Ireland African Alliance for Non-Communicable Diseases and the UK and Ireland Global Cancer Network.

The Global Health Programme also collaborates with the Irish Global Health Network, which brings together people in Ireland and abroad with an interest in global health, facilitates knowledge sharing, organises events, and develops learning and training opportunities.

Prof Weakliam emphasises that much can be learned from other countries, particularly those with limited resources facing health challenges far greater than in Ireland, where the tools and support available are only a fraction of what exists here.

“That is very challenging for them [lower income countries]. They are forced to learn how to use resources to get the best results from their health system. That’s something we can learn, how to be resourceful with what you have. They are very innovative,” he maintained.

“One of the opportunities we have at this point, as the Programme is more established, is to systematically try to capture some learning from those countries and bring it into our own health service planning and strategy.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.