The RSV season has a significant impact on some of our most vulnerable patients and the healthcare system

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is a topical subject given the time of year, and the successful introduction of the HSE’s RSV vaccination programme in infants.

RSV has often been underestimated as a viral infection, but a review of the literature reveals the significance of its global impact as the leading cause of lower respiratory tract infections in children and the number one reason for admission to hospital in children under one year of age.1 Infections and outbreaks have a huge impact on individuals and the health service in terms of cost and resources.2

While the burden of RSV infection is most prevalent in young children, levels of infection are also significant in patients older than 65 years.2,3,4,5

This article provides a comprehensive overview of RSV – focusing on best practice guidance and infection prevention and control (IPC).

Definition and clinical manifestations

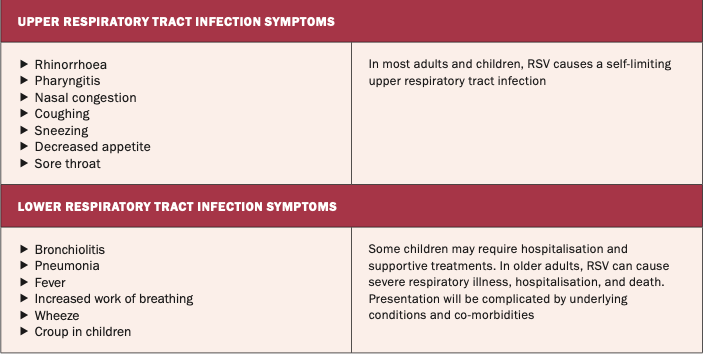

RSV infection can manifest clinically in varying degrees of severity, from upper respiratory tract infection to bronchiolitis, tracheobronchitis, or in most severe

cases, pneumonia.1,2,3,4,5

RSV is found within the genus Orthopneumovirus, and is a negative sense, single stranded, enveloped ribonucleic acid (RNA) virus.6,7 Microscopically, it is the merging of the membranes of cells known as syncytia that have given RSV its name.8

Once the virus comes in contact with the mucosa of the eyes, nose, or mouth, it infects the epithelial cells of the upper and lower airways.2 The initial symptoms of RSV can be similar to a cold, and depending on the severity of the infection, the infected individual can develop symptoms such as a cough, wheeze, rhinorrhoea, fever, and sore throat (see Table 1).9

It is important to note that the majority of people will have a mild illness, but for vulnerable individuals, RSV can cause serious infection.3,4 In Ireland and other countries of the northern hemisphere, RSV is considered seasonal. Peak infection rates are observed in the autumn and winter months, which is considered to be the result of the virus becoming more stable in colder temperatures, with potentially dormant virus becoming activated and increased human susceptibility.8 Typically in Ireland, the RSV season extends from October to March.9

Prevalence and impact

Globally RSV causes significant infection, ranging from mild self-limiting infections to those requiring hospital admissions. Estimates are around 33 million cases annually, with hospitalisation of 3.6 million children and infants under the age of five years.10 Hospitalisation of the sickest patients has a huge impact on the individual, with significant socioeconomic burden and financial impact on the healthcare system also.

The Health Information and Quality Authority (HIQA) highlights that in 2022 alone there were 2,500 paediatric hospital admissions related to RSV in Ireland (the majority to an intensive care unit (ICU) setting), diverting limited resources and disrupting care pathways within the paediatric service.11

The Respiratory Virus Notification Data Hub12 reports a weekly epidemiological summary of respiratory viral illnesses, including RSV, nationally – outlining data on confirmed cases, hospitalisations, ICU cases, outbreaks, and deaths from the infection. This provides practitioners with a valuable resource to track trends in infection and help inform required resources within healthcare systems.

The impact on children is well documented throughout the literature. Most infants will have been infected by RSV by the age of two years and its impact on hospitalisations is considerably higher than for influenza.13 Risks for infection with RSV are higher for premature babies.8 As discussed, thankfully the vast majority of children recover from RSV, but it has been estimated that RSV caused the deaths of 100,000 children in less than five years worldwide.13

The HSE recently said that, prior to the introduction of the RSV programme, each winter four out of every 100 infants were hospitalised due to RSV, with some babies needing special treatment in ICU. A further 50 out of every 100 infants were infected with RSV and many needed medical care from their GP, pharmacist, or paediatric emergency department.

A concerning finding is that children who have been infected with RSV within their first year have an increased risk of wheeze and pulmonary obstruction for many years to come, with a history of RSV being associated with the development of asthma.8

It is a general consensus that RSV in the older adult population (>60 years) is underestimated, possibly due to misdiagnosis.14 As with children, infections can be mild, but recent evidence highlights that hospitalisations and the socioeconomic burden of RSV can be as severe as influenza.15 The risks associated with RSV are complicated with older adults due to comorbidities like chronic lung, heart, and renal disease; diabetes; immunocompromising conditions; and increasing frailty.15 As healthcare workers, we must be cognisant of the fact that the burden on our healthcare systems is projected to intensify in line with the predicted increases in the global ageing population.16

Mode of transmission, incubation, and infectious period

It is essential to understand how RSV is spread to inform appropriate IPC measures. Unfortunately, the virus is highly contagious and spreads very easily through coughing and sneezing.6 The mode of transmission is droplet infection,8 which can be direct or indirect.17 Direct transmission occurs when a person with RSV coughs or sneezes, and droplets from the infected host enter the mucosa of the eyes, nose, or mouth of another individual. Indirect transmission of RSV occurs when a person comes in contact with droplets from the infected person in the environment – for example, on a contaminated surface or the hands of the healthcare worker.17

Incubation period – the interval between exposure to the RSV and presentation of the first symptoms – is typically two-to-eight days.9 The infectious period is considered to be three-to-eight days.9 An important consideration for healthcare workers, particularly when considering transmission-based precautions, is that an individual will remain infectious for as long as the virus’s RNA particles are being shed, which may be prolonged in immunocompromised patients.7

IPC measures to prevent transmission

A helpful visual aid to understand the role of IPC measures in preventing the transmission of RSV is the chain of infection (Figure 1).18

The reservoir of the infected agent (RSV) is present in the airways of the infected individual (reservoir) – which when the person coughs or sneezes (portal of exit), is transmitted directly through the air or via a healthcare worker’s hands (mode of transmission). The mode of entry is the upper respiratory mucosa and the susceptible host is your patient contact. Breaking the chain of infection at any point will prevent the spread of infection. This is where key IPC precautions come into play. These precautions have become so familiar to us over the past few years, but back to basics is key, with a mixture of standard and transmission-based precautions coming into play:17

Hand hygiene as per the World Health Organisation’s five moments is essential. Either alcohol-based hand rub or soap and water is effective. It is essential for both staff and patients alike to carry out regular hand hygiene, reducing the risk of infection to themselves and others, and reducing contamination of the environment.

Respiratory/cough etiquette: The infected patient should be advised to use a tissue when coughing and sneezing (or coughing into the crook of their elbow when a tissue is not available). The tissue should then be disposed of and hand hygiene performed.

Isolation: If a hospitalised patient is symptomatic of a respiratory viral illness, isolation in a single occupancy room, ideally with en-suite facilities, is advised. If RSV has been diagnosed, patients may be cohorted in a multi-bed area where isolation capacity is limited.

Environmental cleaning is a key component of reducing transmission by managing the contamination of surfaces and patient equipment. Research has shown that RSV can remain viable on non-porous surfaces for up to six hours.7

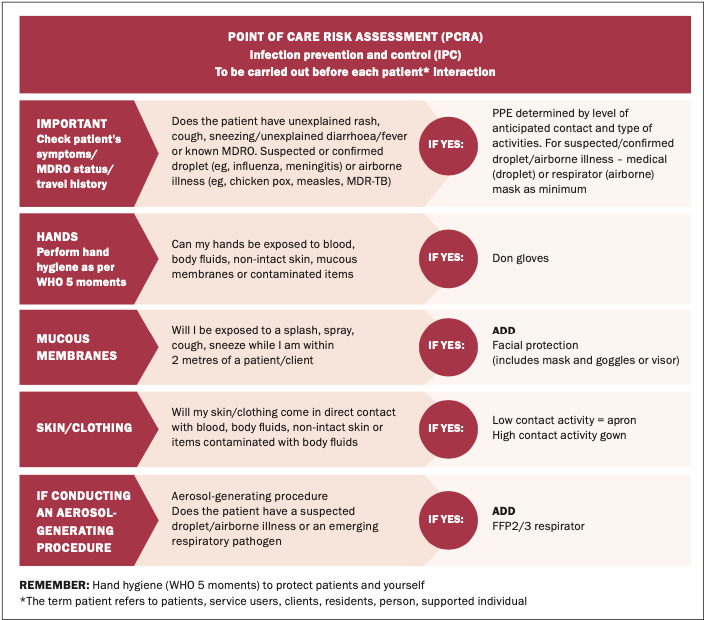

Appropriate use of personal protective equipment (PPE) including the use of masks, gloves, and apron. As always, a risk assessment is advised, with the choice of PPE dependent on a number of factors, including the patient care task involved. Nurses and other healthcare workers are directed to carry out a point-of-care risk assessment (PCRA) prior to patient contact (Figure 1).19

Diagnosis

It can be difficult to distinguish RSV from other respiratory viral illness like Covid-19 or influenza based on clinical presentation and symptoms alone, which can be very similar. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing in the laboratory is currently the gold standard for diagnosis, using swabs from the nose and throat or other samples such as sputum or nasopharyngeal aspirate.9 Point-of-care testing is also available in the form of lateral flow/antigen tests. Diagnosis of RSV in the inpatient setting can be very beneficial to guide supportive treatments, cohorting of patients, and outbreak prevention and management.

Treatment

There is no specific treatment for RSV, so the focus is on supportive measures and managing symptoms.9 Supportive measures include managing fever, keeping the patient hydrated, and oxygen therapy where required. There are antiviral treatments available for RSV, but their development has not been as rapid or widespread as those used for influenza or Covid-19.21

Immunisation programmes

Ireland introduced a highly successful RSV vaccination/immunisation programme for babies in the winter of 2024/2025, utilising the nirsevimab vaccine. It is, however, incorrect to call it a vaccine – it is actually a laboratory-produced monoclonal antibody, which provides passive immunity protection against RSV.22 An advantage of utilising a monoclonal antibody is that when administered to babies, ideally at birth, it will immediately provide immunity – protecting the baby from RSV infection for the winter season.22

The therapy requires a once-off administration, making it a practical option for delivery and supporting compliance. The National Immunisation Advisory Committee (NIAC) have a number of high-level recommendations regarding the use of nirsevimab for the vaccination of infants at various stages up to the age of 24 months, which have been adopted by Government in the Pathfinder 2.0 RSV Immunisation Programme.23

The statistics from the initial vaccination programme were very impressive, resulting in the extension of the programme into the current winter season.24

The HSE provided the following analysis of the impact of the RSV immunisation programme last year:24

Almost 22,500 babies were immunised;

83 per cent of those offered immunisation accepted it for their babies.

Among those immunised (compared to similar babies the previous year who were not immunised), there was a significant decrease in the impact of RSV including:

65 per cent reduction in total number of cases;

57 per cent reduction in cases presenting to emergency departments;

76 per cent reduction in babies requiring hospitalisation;

65 per cent reduction in babies needing intensive care due to complications of RSV.

The RSV catch-up programme during September and early October 2025 achieved a national uptake rate of 45.5 per cent amongst eligible infants. The RSV immunisation programme targeting newborn babies has so far achieved a cumulative uptake of 89 per cent since the programme commenced on 1 September.

The HSE wants to continue to build on that and ensure that as many babies as possible are protected from RSV this winter. The HSE is thus now strongly advising parents of babies born between 1 March to 31August 2025 who did not avail of the opportunity in September to book early to ensure their baby is protected ahead of any surge in RSV infections. New RSV immunisation appointments will be available for a limited period of time from 17November to 12December in clinics across the country.

While RSV vaccinations have been developed for adults, they are currently not part of established national immunisation programmes in Ireland, but can be sourced privately.11 Rationale for this has been provided by the HSE in terms of risk versus benefit, cost, and practicality of immunising a huge patient population.11

Conclusion

RSV has always been associated with infection in children and neonates, but as discussed, has increasingly had an impact on our older patient population in recent years. While many infections are self-limiting, more serious infections require treatment and hospitalisation – having a significant impact on our hospital capacity, particularly in the winter months.

Infection varies from mild upper respiratory symptoms to severe bronchiolitis and pneumonia. A multimodal approach to RSV is key. It is essential that healthcare workers have a working knowledge and understanding of its mode of transmission and the standard and transmission-based precautions that can be employed to prevent onward spread to our vulnerable patients. Much treatment is supportive, but there is a role for antivirals in the management of severe infection among certain patient populations. Prevention is our best option. The vaccination programme in neonates has been a huge success and debate continues around extending this to the older population.

References

1. Bont L, Checchia PA, Fauroux B, et al. Defining the epidemiology and burden of severe respiratory syncytial virus infection among infants and children in western countries. Infect Dis Ther. 2016;5(3):271-298

2. Sethi S, Murphy TF. RSV infection – not for kids only. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(17):1810-1812

3. Shi T, Denouel A, Tietjen AK, et al. Global disease burden estimates of respiratory syncytial virus-associated acute respiratory infection in older adults in 2015: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect Dis. 2020;222(Suppl 7):S577-S583

4. Hansen CL, Viboud C, Chaves SS. The use of death certificate data to characterise mortality associated with respiratory syncytial virus, unspecified bronchiolitis, and influenza in the United States, 1999-2018. J Infect Dis. 2022;226(Suppl 2):S255-S266

5. Teirlinck AC, Broberg EK, Stuwitz Berg A, et al. Recommendations for respiratory syncytial virus surveillance at the national level. Eur Respir J. 2021;58(3):2003766

6. Griffiths C, Drews SJ, Marchant DJ. Respiratory syncytial virus: Infection, detection, and new options for prevention and treatment. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2017;30(1):277-319

7. Kaler J, Hussain A, Patel K, Hernandez T, Ray S. Respiratory syncytial virus: A comprehensive review of transmission, pathophysiology, and manifestation. Cureus. 2023;15(3):e36342

8. Piedimonte G. RSV infections: State of the art. Cleve Clin J Med. 2015;82(11 Suppl 1):S13-S18

9. National Immunisation Advisory Committee. Immunisation Guidelines for Ireland: Chapter 18a Respiratory Syncytial Virus. Dublin: NIAC; 2025. Available at: www.hiqa.ie/reports-and-publications/niac-immunisation-guideline/chapter-18a-respiratory-syncytial-virus

10. World Health Organisation. Respiratory syncytial virus. Geneva: WHO; 2025. Available at: www.who.int/health-topics/respiratory-syncytial-virus

11. Health Information and Quality Authority. Plain language summary of the rapid health technology assessment of immunisation against respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) in Ireland. Dublin: HIQA; 2024

12. Health Service Executive. Respiratory Virus Notification Data Hub. Dublin: HSE; 2025. Available at https://respiratorydisease-hpscireland.hub.arcgis.com/pages/rsv

13. Munro APS, Martinón-Torres F, Drysdale SB, Faust SN. The disease burden of respiratory syncytial virus in Infants. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2023;36(5):379-384

14. Recto CG, Fourati S, Khellaf M, et al. Respiratory Syncytial Virus vs Influenza Virus Infection: Mortality and morbidity comparison over seven epidemic seasons in an elderly population. J Infect Dis. 2024;230(5):1130-1138

15. Maggi S, Veronese N, Burgio M, et al. Rate of hospitalisations and mortality of respiratory syncytial virus infection compared to influenza in older people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccines (Basel). 2022;10(12):2092

16. World Health Organisation. Ageing and health. Geneva: WHO; 2025. Available at: www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health

17. Department of Health. NCEC National Clinical Guideline No 30 Infection Prevention and Control Volume 1. Dublin: DOH; 2023. Available at: www.gov.ie/en/department-of-health/publications/infection-prevention-and-control-ipc/

18. Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology. Break the chain of infection. 2016. Available at: https://infectionpreventionandyou.org/protect-your-patients/break-the-chain-of-infection/

19. Antimicrobial Resistance and Infection Control. How to use a point-of-care risk assessment for infection prevention and control. HSE RESIST; 2025. Available at: www.hse.ie/eng/about/who/healthwellbeing/our-priority-programmes/hcai/resources/general/

20. Antimicrobial Resistance and Infection Control. Point of care risk assessment. HSE RESIST. Available at: www.hpsc.ie/az/microbiologyantimicrobialresistance/infectioncontrolandhai/posters/PCRAResistPoster.pdf

21. Ferruggia F. The role of antivirals in managing RSV infections. Pharmacy Times. 2025. Available at: www.pharmacytimes.com/view/the-role-of-antivirals-in-managing-rsv-infections

22. Drysdale SB, Cathie K, Flamein F, et al. Nirsevimab for prevention of hospitalisations due to RSV in infants. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(26):2425-2435

23. Health Service Executive. RSV 2.0 Immunisation Pathfinder SOP and Implementation Tools. Dublin: HSE; 2025. Available at: www.hpsc.ie/az/respiratory/respiratorysyncytialvirus/immunisation/rsvimmunisationpathfindersopandimplementationtools/

24. Health Service Executive. HSE extends very successful programme which protects babies from RSV in Winter. Dublin: HSE; 2025. Available at: www.hpsc.ie/news/hse-extends-very-successful-programme-which-protects-babies-from-rsv-in-winter.html

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.