As we mark European Heart Valve Disease Awareness Week (www.heartvalveweek.eu) this month (16-22 September), it is important that patients understand that progress and changes in the treatment of heart valve disease make the disease a little less daunting

The landscape of

cardiac surgery is changing with lightning speed. Cardiac surgery has been the

focus of much innovation and there have been many exciting developments, such

as the introduction of minimally-invasive surgical valve replacement/repair

techniques and transcatheter technologies.

Last month, our team in Galway University Hospital

replaced the mitral valve of an elderly 86-year-old lady who was in acute heart

failure due to severe valve regurgitation, using a minimally-invasive

technique. The procedure was performed via a 4-5cm incision, with the aid of a

thoracoscope instead of the conventional sternotomy approach, which is more

invasive.

This procedure, as well as a number of other procedures,

was performed under the guidance of Prof Mattia Glauber, a world-renowned

Italian cardiac surgeon. Prof Glauber has carried out over 10,000 cardiac

interventions, 3,000 of which were performed via a minimally-invasive

technique.

The minimally-invasive approach obviates the need to open

the sternum, reducing pain significantly and allowing for a faster recovery

with less risk of infection. Without this option, I would have been concerned

about the aforementioned patient’s ability to withstand the rigours of

conventional open surgery and the subsequent recovery.

These technological and surgical innovations are great

news for the main cohort of patients who typically need such procedures. The

incidence of heart valve disease generally increases from the age of 70 years

onwards, so, advantageously, the age group that needs the procedures are also

those who will benefit most from the innovations.

This is a hopeful message for GPs to deliver to their

patients. Being referred for heart surgery is no longer a ‘death sentence’.

Instead it is an opportunity for many to continue living their lives in a much

better way than they could have hoped to have previously.

Heart valve disease

This month, I

worked with Croí, the heart disease and stroke charity, to help promote

European Heart Valve Disease Week, which took place from September 16 to

22 (www.heartvalveweek.eu).

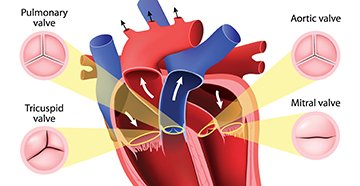

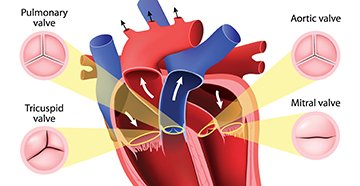

One-out-of-eight people over the age of 75 years suffers

from heart valve disease, which involves degeneration to one or more of the

heart’s valves. There are two main types of valvular disease: Aortic valve

stenosis, and mitral valve regurgitation. Valvular disease, when progressed to

the severe stage, significantly limits a patient’s functional ability and life

expectancy.

For example, in the case of patients with severe aortic

stenosis, the survival rate is as low as 50 per cent two years after the onset

of symptoms and 20 per cent at five years.

The great news is that heart valve disease can be treated

— a diseased valve can either be repaired or replaced by open surgery or where

deemed appropriate, via a minimally-invasive approach.

Many symptoms of heart valve disease develop gradually and

patients often adapt their lifestyle in response to them or simply mistake

their symptoms as being traits of ageing, particularly as they include

shortness of breath, chest pain or tightness, reduced physical activity,

fatigue, rapid or irregular heartbeat, feeling faint or fainting upon exertion.

However, people with heart valve disease do not always

display symptoms, even if their disease is severe.

A clear indicator of valve disease can be the detection of

a heart murmur via stethoscope exam by a GP, followed by a referral for an

echocardiogram for a more accurate diagnosis.

It is important to highlight the issues around heart valve

disease because many patients are not aware of its existence or potential

impact. A recent survey of more than 12,820 people who are 60 years and older

across Europe found that aortic stenosis is one of the heart conditions that

people are least familiar with. Only 3.8 per cent of respondents knew what

aortic stenosis was or that it is the most common form of heart valve disease.

Although awareness increases with age, 30 per cent of respondents over the age

of 65 reported knowing nothing about heart valve disease.

Congenital bicuspid valve

What can sometimes

be unexpected is the subgroup of younger patients who present with valvular

failure due to a congenitally bicuspid aortic valve. These patients have a

congenitally abnormal aortic valve, whereby they have only two leaflets instead

of the usual three. This happens to 1-to-2 per cent of the population and leads

to early degeneration of the aortic valve.

These patients tend to be underdiagnosed and undertreated,

possibly because presentation is generally less acute and insidious. For

example, recently, I had an extremely fit patient in his early 50s who

presented with what was thought to be pneumonia but it was in fact heart

failure due to valve failure.

When asked about other prior symptoms, the patient noted a

decreased capacity to run, reducing regular running distance from 10km to 7km

due to exhaustion. Other than that, he didn’t really notice much else.

Interestingly, this patient worked in the medical field and still did not

attribute his symptoms to a cardiac cause.

Role of the GP

The role of the GP

when dealing with valvular disease is many-fold. In the first instance, GPs act

as the first port of call for diagnosing valvular disease. Our role as cardiac

interventionalists is to determine the severity of the valvular disease and

decide upon the correct treatment plan. For this, we work in close

collaboration with our cardiology colleagues to ensure the most up-to-date and

appropriate treatment is delivered to each individual patient. Another

significant role that GPs play in the management of heart valve disease is to

act as a patient advocate, alleviating the fear and worries of the patient. In

Ireland, GPs are highly respected and are trusted implicitly by their patients.

Therefore, the understanding and awareness that GPs have of the available

armamentarium of treatment is of the utmost importance. GPs have the ability to

educate and indeed, comfort patients and their role must not be underestimated.

Case report 1

A 56-year-old female patient presented

to her GP with suspected flu. She was brought as an emergency by ambulance and

admitted to hospital immediately. Subsequent investigation diagnosed bacterial

endocarditis involving both the aortic and mitral valves. Replacement of the

mitral and aortic valve was performed within 48 hours of admission by the

cardiac surgical team.

The

patient recovered well from her surgery.

However, due to the need for prolonged antibiotic therapy, the patient spent a

total of 10 weeks in the hospital postoperatively. She is now well and

thriving.

Case report 2

A 68-year-old male patient who worked

in the hospital setting was diagnosed with mild aortic valve disease following

routine investigations. He then became symptomatic a few years later and

subsequent investigation revealed his aortic valve disease had become severe in

nature. This prompted surgical aortic valve replacement. The patient’s surgery

was uneventful. He spent one week in hospital postoperatively and six weeks

recovering, with no further incidents. He is currently well and enjoying

life.

The

patient was empowered to seek treatment and as a result of this, he has had a

good result. If he had not been as proactive or had postponed seeking help and

ignored his symptoms, his life expectancy would have been significantly

reduced. It is of utmost importance that patients take that first crucial step

and talk to their GP. Early intervention is a key component to successful

treatment of heart valve disease.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.