Dr Lisa McNamee describes the healthcare concerns of a community in east Namibia and reports on a conservation medicine course run by a foundation in the locality

Between the Namib and Kalahari deserts, in one of the driest and most sparsely populated areas in the world, lies Namibia, stretching for nearly a million square kilometres. This arid, breathtaking environment is where the N/a’an ku sê foundation practices conservation medicine, focusing on wildlife conservation and providing healthcare to the remote San community.

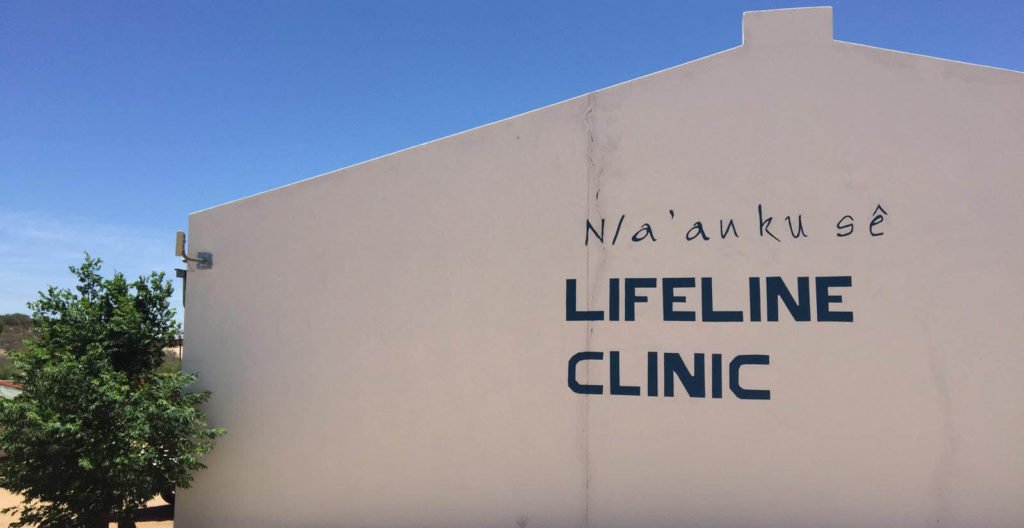

In 2003, Dr Rudie van Vuuren founded the Lifeline clinic in isolated east Namibia. A preventable death of a child from the local San community exposed the need for a dedicated primary care facility. The San bushmen are a nomadic and marginalised people who, for many reasons, have difficulty accessing healthcare. The clinic, staffed by international doctors and local translators, offers free primary care to the San, as well as transfer to secondary care when required. For several years, the N/a’an ku sê foundation has run a conservation medicine course that demonstrates successful remote healthcare delivery in a nomadic population.

Conservation medicine places human health in its environmental context and considers human health, animal health and the local environment in tandem. In a part of the world where desertification, poaching and animal health have a real impact on healthcare delivery, it makes sense to consider these issues together. During the course, there was clinic exposure, outreach work in the local villages, tuberculosis (TB) surveillance and trauma teaching, as well as a focus on survival skills in the African bush, African zoonosis teaching, infectious diseases, and anti-poaching methodology.

The clinic itself provides free primary care to approximately 3,500 patients a year, some travelling up to 200km to attend. Paediatric presentations are frequently related to acute or chronic malnutrition, with food and water security a constant issue. During clinics, doctors were often unable to use their WHO paediatric centile charts to measure growth, such was the degree of stunting frequently seen in the under-twos. Parents presenting for an acute issue might have chronically malnourished children who are then hospitalised for nutritional support. As well as acute presentations, the clinic also provides basic primary care services such as baby checks, vaccinations, and health information sessions in the local language.

TB

Infectious diseases such as TB, malaria and HIV are also common presentations. TB is endemic in Namibia, with the fifth-highest incidence of TB worldwide. The San community’s risk of contracting TB is 15 times higher than that of the general Namibian population. Due to low healthcare literacy, medication adherence is poor and the risk of resistant strain development is high. Patients are incentivised to return for their TB medications with high-energy food supplements such as Plumpy’nut, which are distributed with medications from the clinic. Patients who require hospitalisation are transferred via uneven dirt roads to the nearest hospital in Gobabis, 120km away. With support from the STOP TB Partnership, there is a TB programme running from the Lifeline clinic that includes outreach work into the local villages with a doctor, translator and medications once a week. Dr van Vuuren is planning to build a TB ward in addition to the primary care clinic, where nomadic patients can stay and be monitored through initial treatment.

Socioeconomic and lifestyle issues

Many of the San health problems are related to socioeconomic issues. They are a widely-dispersed people, nomadic traditional hunter-gatherers who have low educational levels and often live in extreme poverty. Respiratory problems are frequent due to cooking on open wood fires, often in restricted quarters. Sanitation is poor or non-existent. Delayed presentations are common, due in part to the enormous distances they have to travel, often on foot, for care. There are no effective social services and due to chronic food insecurity, malnutrition often leads to stunting, and acute physical wasting.

Alcohol is a particular problem in Epukiro, where the Lifeline clinic is based, as the health educational level is low and alcohol is cheaply available. Combined with their small stature and weight, alcohol tends to cause more problems for the San than the general Namibian community. The clinic staff try to educate women of child-bearing age of the dangers of drinking during pregnancy, but the practice is still reasonably widespread.

Patient education is a key feature of both the outreach work and day-to-day clinic appointments in the Lifeline clinic. Long-standing discrimination against the San within Namibia has contributed to low expectations of treatment, delays in accessing healthcare and frequent early cessation of treatment. The San are now the only ethnic group in Namibia to experience a decline in health and life expectancy since the country’s independence in 1990. The life expectancy for a San man is 48 years old, in comparison with 64 years for a non-San Namibian.

During a course I attended at the foundation’s main conservation lands, near the capital Windhoek, participants were introduced to the main concepts of conservation medicine. Research is a key component of both the Lifeline clinic’s activities, as well as the wildlife conservation work in N/a’an ku sê. This research is usually longitudinal and is influencing policy within Namibia on ecological health and future planning.

Environment and wildlife

Human effects on the health of the planet here are evident, particularly the damaging effects of climate change, with increasing periods of drought and desertification evident all around. A key focus here is landscape conservation — replanting vegetation, attempting to limit desertification, preventing overgrazing, no off-road driving, reforestation through strategic replanting, and grey water recycling from human and animal activities. The end result is promoting human health by maintaining the integrity of the landscape essential for both wildlife and human survival.

Human-wildlife conflict mitigation has been another key tenet of the approach. As desertification continues to impact both wildlife territory and farmland, there is increasing conflict between farmers and particularly with the cheetah and jaguar that have begun hunting on their lands.

As wildlife tourism is key economically for Namibia, preventing the cull of the big cats is vital. The approach that the N/a’an ku sê foundation has taken is to become a contact that the local farmers can call when a big cat is encountered. Their vets can trap and tag the animal so that its hunting range is mapped out on GPS, which allows farmers to move their livestock into other areas. This minimises livestock casualties, prevents the predators getting shot and reduces the risk of injury to farm workers.

Due to their interconnected way of living, there is no clear dividing line between animal and human health. Carnivore research produced benefits for the human population, and studies of elephant migration patterns lead to less human-animal conflict over water supplies. African zoonosis was a focus of many talks from our veterinary colleagues as having a major impact locally on human health. Wildlife is a difficult-to-monitor reservoir of infection, an impossible population to vaccinate, but one that was having more frequent contacts with humans due to desertification and the reduction in habitat. Antelope, baboons and rodents were all noted as potential reservoirs of zoonotic disease, carriers of rabies, haemorrhagic fevers, plague, and myriad transmissible viral illnesses.

At our main base during the course, there was an outdoor sink and toilet with running water drilled from approx 200m underground from the water table. We were warned not to leave our toothpaste outside, as the local baboon population had developed a taste for it, and it would be stolen and eaten. Although the orphaned baboon babies in the conservation area were mischievous rather than dangerous, stealing human food, and tugging at people’s earrings, we were careful to leave nothing outside that might draw the enormous and potentially dangerous adult baboons near us overnight.

Namibia has a high proportion of venomous snakes, including cobra, boomslang and most notoriously, the black mamba. When they venture into human settlements there are a handful of snake-catchers, or experienced snake-handlers, on call to deal with them. Snakebite management and definitive care was taught by one of the experts in the region and the practical management was demonstrated by a professional snake-catcher working locally. The snake-catcher had been bitten in the past by a black mamba and survived to relate the experience to others. Demonstrating how lucky he was to survive, he wore a t-shirt with a slogan that read, ‘What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger, except the black mamba — that **** will kill you.’ Participants were shown the standard bush method of testing whether a snake had injected venom into the bite wound after someone has been attacked. A blood sample is taken and if it coagulates quickly in the sample pot, it’s possible to tell if venom had been injected into the wound. A crude but effective test, it allows medics to determine which patients are in need of evacuation to the nearest centre with intensive care facilities in Windhoek before the venom spreads.

Between the veterinarians working with local wildlife and injuries sustained by the local population, trauma is another presentation that the team here must manage. They are varied presentations, from animal bites, goring injuries from a tusk or long tooth, to various foot injuries from the many heavily-thorned plants that survive in the desert. They all must be irrigated and often debrided at the local facilities before the more serious injuries are evacuated to definitive care at the capital’s hospital.

The last evening of the conservation medicine course was a traditional Namibian braai, a large barbeque of boerewors sausage cooked in a large barbeque pit, surrounded by large sharp branches pitched securely in the ground on all sides. When asked what the purpose of these barriers was, the head of the local anti-poaching force smiled and said it was “to keep away the elephants — a stampede would ruin dinner”.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.