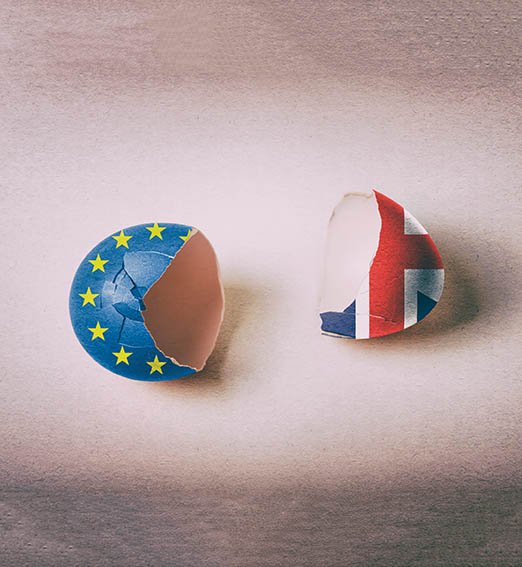

With a further delay to Brexit until late October, the issue continues to loom over Irish healthcare. David Lynch talks to doctors and organisations about concerns over what a ‘disorderly’ Brexit may bring

Brexit fatigue’ may be an understandable condition, resulting from the unending news coverage, the missed deadlines, and the apparently ceaseless complicated votes in the British House of Commons. Even if the process is proving somewhat exhausting, Brexit remains a major challenge to Irish healthcare, both in the Republic and across the island.

Irish healthcare, and doctors in particular, face some unique difficulties because of the coming UK split from the EU.

Prof Trevor Duffy, Consultant Rheumatologist, Connolly Hospital, Dublin, and former IMO President, is a member of the Organisation’s International Affairs Committee. Over the last couple of years, in this capacity, he has spoken at various forums both nationally and internationally about Brexit.

Considering his international work with the IMO, it is perhaps no surprise that many of the doctors that Prof Duffy meets are generally against Brexit.

“Most I come across are bewildered by it; they just can’t understand it,” Prof Duffy told the Medical Independent (MI).

“The doctors I would see in the UK are by their very nature doctors who are engaging internationally and they very much get the value of international collaboration.

“They would very much be ‘Remain’ in mentality and I suppose exasperated by the whole process.”

Dr Denis McCauley is a GP who lives and works in Co Donegal. He is also Coroner for the county.

Dr McCauley said he is not inclined to speculate on how doctors on either side of the border may feel about the Brexit vote itself. However, he did say the impact of any possible ‘hard border’ on his locality would be clearly felt.

“I am old enough to remember what a hard border actually was,” Dr McCauley told MI.

“I can remember my father being stopped at the border, giving in his papers, then he had to be over the border and back from Derry by six in the evening, or else he would have to stay in Derry and then explain to the customs men why he was actually delayed.

“I can understand what that actually meant. I can understand all the problems and the disruption to living that it actually caused. So I’m naturally concerned because I want the prosperity and peace that the [open] border has brought, to remain.

“And any interference with that very, very delicate ecosystem [is a problem]. We have seen in Derry [referring to the recent riots, violence and murder in that city] all it takes [is] one stupid act to start the whole thing over again. That naturally makes me concerned.

“Am I deeply worried? No. But there is a background concern all of the time as to what will happen. So I suppose you can say there is anxiety.”

Planning

In terms of the Irish Government’s planning for Brexit, Prof Duffy has deep concerns that a focus on health “has been lacking”; however, he does not principally blame the HSE or Department of Health for this.

“On the one hand, I am not aware of the high-level detail of their engagement [but] I think, unfortunately, health has really been left behind both here and the UK. If you talk to UK [medical] professionals, they suffer from the same problems in regards to Brexit planning,” Prof Duffy said.

“Health has fallen far down the agenda behind economics, trade and employment, and the Good Friday Agreement and I think Government is trying to grapple with all that. So I don’t think health has really featured appropriately in terms of planning and considerations, either here or in the UK. It has been lacking.

“I would not fault the HSE as such for that. But it is about getting health on the larger Government table either here, the UK, or in Europe.

“These other issues have taken the limelight and I think the HSE is perhaps struggling the same way as we in [the medical] profession are, in terms of getting a hearing for health.”

Prof Duffy conceded that even if health had been a stronger focus, inherent difficulties would still arise.

“The other side is that health is so complex,” he said.

“I think it’s very hard to really plan for Brexit when there are so many different complications that might come out of a Brexit solution and how that might impact the import and export supply chain, data transfer, professional qualifications recognition, regulations around healthcare quality — it’s just so broad, it’s very hard to plan for.”

From his border-based viewpoint, Dr McCauley agreed that the HSE and the Department are somewhat restricted in the planning they can do for the myriad of eventualities and unforeseen consequences inherent in Brexit.

“I think it really is so difficult for them; you don’t know [what will happen], I don’t know, neither does the Minister [for Health],” he said.

“There will be undertakings given; there would be forward planning in relation to this. And I am sure they have different scenarios planned, each of which will have a different outcome.

“But at the present minute, we don’t know, because at the moment each particular possible situation with Brexit has different outcomes so there would have to be different planning. So with the best will in the world, when you are dealing with healthcare, unless you know what is exactly happening, option planning doesn’t always work well.”

Regarding planning, Dr McCauley said, ultimately, he thinks that “common sense will prevail. But common sense has not prevailed within Brexit so far. So we can’t be complacent in that regard.”

The Department’s most recent public update on its Brexit preparedness was provided on 17 April on the Government of Ireland website.

Cost

Asked about the estimated financial cost of a ‘no-deal’ Brexit would be to the Irish health service, a Department spokesperson tells this newspaper it could not provide a figure.

“As with all aspects of the Irish economy, a no-deal Brexit could have an economic impact on the health service, including but not limited to the cost of providing cross-border services, cross-border prescriptions and, if necessary, the provision of EHIC [European Health Insurance Card] cards for Irish citizens in Northern Ireland,” the Department spokesperson told MI.

“There could also be cost increases for medicines, medical devices, healthcare consumables and products, depending on the nature of Brexit and its effect on the market for such products. Financial issues including currency fluctuations, VAT, potential new tariffs, costs of medicines, medical supplies and other consumables currently procured in the UK could also lead to increased costs.

“At this stage, it is not possible to determine the financial impact of the above issues, as they involve a range of stakeholders and variables.”

The spokesperson added that the Department cannot estimate the cost of an “agreed Brexit”.

“The Department of Health and agencies under the aegis of the Department have been engaged in extensive Brexit planning since the UK voted to leave the European Union in 2016, including contingency planning for a no-deal Brexit since December 2018 in line with Government policy, to ensure, as far as is possible, that the health sector is prepared for any adverse impacts as a result of Brexit. Brexit planning involves many units and staff within the Department,” according to the spokesperson.

Asked how many staff are involved in the preparation, the spokesperson did not provide an exact figure, adding “staff in different units across the Department are involved in Brexit preparation as required from time-to-time. A number of staff in the International Policy Unit are assigned to Brexit work full-time.

“The Department is working to prepare the health sector for possible adverse effects of Brexit and is reasonably assured that the sector is well prepared.

“The Government is proactively working to ensure that the people of Northern Ireland can continue to enjoy access to EU rights, opportunities and benefits into the future, as they do today — including in relation to EHIC.”

Concerns

Both Prof Duffy and Dr McCauley warned that the impact of Brexit on health will be real, despite the difficulty in predicting the details.

“I think the prime concern is that in a sense, healthcare is all about collaboration really,” Prof Duffy said.

“Collaboration through Europe has grown in healthcare in the case of patients travelling, shared knowledge, professionals sharing knowledge and working in a collaborative way. And I suppose for us in Ireland, the most tangible example of that is working with healthcare in the UK.

“Be that people training in the UK, people coming here helping with exam processes, patients going to the UK. Say also, for example, patients coming from Northern Ireland and going to the south. But really, whatever way you look at it, healthcare is ultimately a collaborative industry and a small island like this needs Europe. And our closest neighbour both in terms of geography and historically has been the UK.

“To lose them [the UK] as a result of regulatory barriers that will automatically crop up as a result of Brexit would be a shame and set us back decades.”

Prof Duffy said that the possible impact will also be felt most clearly by patients.

“In the cross-border region, one of the great successes over the last 10, 15 years has been the growth in collaboration of GPs… that work seamlessly across the border… specialist services like the paediatric cardiac surgery service that works in Crumlin for the whole island.

“Things like radiotherapy services that sit on the north of the border but service the north-west of the Republic, similarly, cardiac services are shared… all of that risks falling asunder. There are more examples of where [cross-border health] has worked.

“Then on a professional developmental basis, I can’t think of a specialist medical society, be it the Irish Society for Rheumatology, or Gastroenterology — I can’t think of a single one that is not a cross-border society.”

Dr McCauley recalls the development of cross-border health cooperation in recent decades.

“It has gone from two systems ignoring each other with the only interface being an emergency. Then it evolved. What helped it was the BSE [bovine spongiform encephalopathy] issue; there was a lot of cross-border co-operation from that.”

The system now involves extensive cross-border co-operation with Altnagelvin Area Hospital in Derry, which provides services for people south of the border.

“The development of cross-border healthcare has developed significantly, and I have lived on the border all my life, apart from when I trained in Trinity [College Dublin],” he said.

Uncertainty

“There have been evolutionary changes and it has got [now to] a high level of actual communications. But naturally, there is uncertainty because of Brexit, particularly when it comes to transporting critically-ill patients across the border,” he said.

“When it comes to people having to go into Derry once a week to get radiotherapy, the presence of a border, the uncertainty of one is going to be there and is very worrying.”

However, could Brexit endanger all this progress that has been made in cross-border health co-operation?

“Of course it can,” Dr McCauley warned.

“Medical planning goes on good team-building, information exchange, and it also demands certainty.

“When you are dealing with critically-ill patients, there has to be certainty. That is what you cannot describe with the present situation in Northern Ireland. Whether it is going to be part of a customs union, whether we are going to have a hard border, or a border in the Irish Sea — your guess is as good a mine as to the final configuration.

“So we don’t know. So therefore, that uncertainty interferes with planning. That uncertainty interferes with resource allocation in the coming years… Simply, medicine does not work well with uncertainty.”

Possible problems ahead…

According to the Department of Health’s most recent Brexit Contingency and Preparedness Update, there should be no immediate impact on medicine supplies following Brexit.

“Some of our medicines are moved through the UK to get to Ireland,” according to the document published last month.

“When the UK leaves the EU, Ireland is highly unlikely to face an immediate impact on medicine supplies in the period immediately afterward. This is because there are already additional stocks of medicines routinely built into the Irish medicine supply chain.

“There are a number of healthcare arrangements between Ireland and the UK, including the Cross-Border Directive, the Treatment Abroad Scheme and the European Health Insurance Card. Both the Irish and UK Governments are fully committed to continuing these existing cross-border healthcare arrangements.”

The Health Products Regulatory Authority (HPRA) has kept Brexit on its risk register, this newspaper has been told.

“The UK is due to leave the European Union. How and when they may leave is not yet certain,” according to a HPRA spokesperson.

Risk

“For that reason, Brexit remains within the HPRA’s internal risk register, which is compiled as an output from our risk management system. As is normal practice in risk management systems, all risks will be reviewed on a regular basis.”

Despite Departmental assurance, some organisations still have worries.

When asked what the Irish Cancer Society (ICS) regarded as the most concerning potential impact on the Irish health service, a spokesperson said simply “medicine supplies”.

“Ireland’s supply of compounded chemotherapy drugs is heavily reliant on one supplier in the United Kingdom,” the ICS spokesperson stated.

“While the HPRA has not yet published their critical medicines list to prepare for a no-deal Brexit, the greatest risk is to a small number of products, including radioisotopes, which have a short shelf-life and are used in radiotherapy for cancer patients.

“A disorderly Brexit may mean delays to shipments of medicine supplies at customs, which could have serious implications for cancer patients’ treatment.”

The Society said that commitments to continued service arrangements for cross-border treatment, including radiotherapy, are welcome.

“Radiotherapy services at Altnagelvin Hospital in Derry are available to patients in the north-west. While service level agreements may not be impacted by Brexit, we are concerned about the quite significant practical consequences of a hard Brexit for both patients and staff who cross the border every day.”

A spokesperson for Children’s Health Ireland (CHI) told MI that “in relation to the Congenital Heart Disease (CHD) Network and cardiology services, there is a service level agreement between the Health and Social Care Board (NI) and CHI, which will be unaffected by Brexit, regardless of the outcome.”

Qualifications

The CHI spokesperson said it was working closely with Government departments to prepare for Brexit.

Educational bodies with international remits may also be impacted. “RCSI has a close working relationship with the three Royal Colleges of Surgeons in the UK (England, Edinburgh, Glasgow),” a College spokesperson told MI.

“RCSI has already agreed with the UK colleges that, after Brexit (regardless of whether there is an agreement or not), that the colleges will continue their close co-operation.

“Access to the UK for Irish trainees and surgeons has provided valuable training and career opportunities for Irish surgeons for generations. The EU Professional Qualifications Directive (PDQ) has made it easier for doctors who have qualified in one EU country to satisfy the regulators in other EU jurisdictions. This has also made it simpler for Irish-trained surgeons to work in the UK (and UK surgeons to work in Ireland). RCSI lobbied the Irish Government to include the provisions of the PDQ in the UK’s EU withdrawal agreement.

“We were very pleased to see that the proposed agreement provides for the PDQ to continue after Brexit. Similarly, we hope that any final trade agreement negotiated between the UK and EU will continue to provide for free movement of surgeons between Ireland and the UK and intend to seek the Irish Government’s support for this position.

“In the event that the Brexit agreement fails and the UK leaves the EU without an agreement, Irish surgeons will have to apply to the GMC [General Medical Council] for recognition of their qualifications and experience if they wish to register in the UK for training or career purposes.

“In that case, the fact that surgeons who have completed their training in Ireland will have used the same curriculum and m

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.