Male lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) are a common complaint affecting quality of life (QoL). They can be divided into storage, voiding and post-micturition symptoms. Age has a strong association with symptomatology and most old-aged men will have LUTS but of mild severity, causing minimal bother. There is generally a fear in patients that LUTS are associated with prostate cancer, whereas no definite link exists.

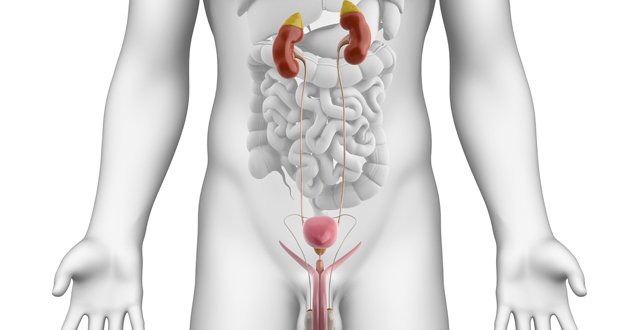

LUTS may not only be caused by bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) secondary to benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), bladder dysfunction, such as overactive bladder (OAB), underactive bladder, anatomical and functional problems of the lower urinary tract can be responsible for a similar clinical picture. Quite often, one sees a mix of these anatomical and functional problems in these cases (see Figure 1).

LUTS are caused by an interplay of detrusor instability, reduced bladder contractility and BOO commonly due to benign prostatic enlargement (BPE). Symptoms can be divided into storage type, such as altered bladder sensation; increased daytime frequency; nocturia; urgency and urinary incontinence; voiding symptoms, such as hesitancy, intermittency, slow stream, splitting of stream, straining and terminal dribble; and post-micturition symptoms, such as post-micturition dribble and feeling of incomplete bladder-emptying.

Most of the patients will present with a mix of these symptoms. A lot of these complaints will impact the patient’s, as well as their partner’s, quality of life.

<h3><strong>Complications</strong></h3>

BOO secondary to BPE can lead to haematuria, acute urinary retention, urinary tract infections, bladder calculi and urinary incontinence can ensue. Severe renal compromise can occur and some cases may present with renal failure.

<h3><strong>Diagnosis</strong></h3>

Clinical history is important to identify potential conditions and associated comorbidities, which will guide further management.

A self-completed validated questionnaire, such as the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) or the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire — Male LUTS (ICIQ-MLUTS), helps to objectively define the severity of a condition and forms a crucial component of assessment. Assessment should include voiding diaries to assess storage symptoms and where applicable, sexual function assessment by a validated symptom questionnaire.

Physical examination should include assessment for full bladder, dependent oedema, as well as assessment of the genitalia. Digital rectal examination should be performed to assess the prostate for any abnormalities and estimation of size. Urine analysis will help to identify a urinary tract infection, haematuria, proteinuria or glycosuria, thereby altering the management algorithm.

There are caveats in checking the PSA (prostate specific antigen) and patients must be carefully counselled for further investigations carrying certain risks in the situation where a raised level is found. PSA itself is a predictor of risk of disease progression in cases of LUTS secondary to BPO, however, it can be elevated with other conditions, including prostate cancer.

Renal function test with estimation of GFR should be available, as some patients will have abnormal renal function warranting further investigation and changing the course of management. Renal ultrasound scan should not be routinely ordered but considered in patients with deranged kidney function. Post-void bladder volume estimation and uroflowmetry are useful adjuncts. Flexible cystoscopy is indicated where there is concern for bladder cancer or urethral stricture.

In the majority of cases, diagnosis can be made with the above. However, in a small subgroup of patients, further investigative options may be warranted. Non-invasive pressure-flow testing, filling cystometry, pressure flow studies and video urodynamic studies are reserved as specialised investigations and are not indicated as routine.

<h3><strong>Treatment</strong></h3>

Not all LUTS cases will require treatment. Exceptions include patients who have already developed complications or those who have progressive symptoms. Clinical evidence suggests that more than half of the patients with LUTS related to BPE will not progress, and these are the individuals who will benefit from avoidance of treatment-related side-effects. For patients with low bother score, mild symptoms and no risk factors, patient education with reassurance and lifestyle advice are usually sufficient with regular follow-up.

Decision for intervention in any form, be it medical or surgical, is a directive of a patient’s symptom severity, clinical progression of disease, individual choice and/or onset of complications.

<h3><strong>Medical treatment</strong></h3>

Medical therapy aims to address the symptoms and alter the progression of disease, while reducing the size of the prostate gland.

<strong>A: Alpha blockers</strong>

α1-adrenergic receptors (α-1A, -1B and -1D) are members of the Gq protein-coupled receptor superfamily. Upon activation, G protein, Gq, activates phospholipase C (PLC). The PLC cleaves phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), which in turn causes an increase in inositol triphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (DAG).

This interacts with calcium channels of endoplasmic and sarcoplasmic reticulum, thus changing the calcium content in a cell, causing contraction of smooth muscle. These are clinically important for the lower urinary tract.

Alpha blockers work by altering the static and dynamic state of prostatic smooth muscle and bladder neck. They can be non-selective, such as phenoxybenzamine; uroselective, such as terazosin, doxazosin and alfuzosin; or highly uroselective (α-1A), such as tamsulosin and silodosin. They have a rapid onset of action. The efficacy is comparable among different agents. Side-effects include retrograde ejaculation, hypotension, dizziness and floppy iris syndrome. These agents provide symptomatic improvement by decreasing IPSS and quality of life scores, but do not alter risk of clinical progression of BOO secondary to BPE.

Alpha blockers improve maximum flow rate and symptom score by 20-to-40 per cent. They neither reduce the size of the prostate nor reduce the long-term risk of acute urinary retention. They should be offered to men with moderate-to-severe symptoms.

<strong>B. 5-α-reductase inhibitors</strong>

5-α-reductase inhibitors are a class of agents that reduce the size of the prostate by inhibiting 5-alpha reductase, an enzyme that converts testosterone to powerful dihydrotestosterone.

Two isoforms of this enzyme exist: Type 1 and type 2. Finasteride inhibits 5-α-reductase type 2, whereas dutasteride inhibits both 5-α-reductase type 1 and type 2. Both agents are equally effective. Side-effects include sexual dysfunction, such as loss of libido, erectile dysfunction, low ejaculation volume and breast tenderness.

They have a slow onset of action (three-to-six months). Overall, after two-to-four years of treatment, these agents improve symptom score by 15-to-30 per cent and decrease prostate volume by about 28 per cent, improving maximum flow rate. PSA levels are reduced by 50 per cent.

They also reduce the risk of clinical progression of disease, such as need for surgical intervention and acute urinary retention. There is no causal relationship between these agents and risk of prostate cancer. Patients on long-term therapy should have their PSA closely followed and be evaluated accordingly.

They should be offered to patients with increased risk of disease progression and/or enlarged prostate.

<strong>C. Combination therapy (α-blocker + 5-α-reductase inhibitors)</strong>

These agents combine the rapid onset of action of an α-blocker with reduction in risk of disease progression by 5-α-reductase inhibitors.

Combination therapy with these agents is superior to monotherapy. It improves symptoms score and maximum flow rate, while reducing the risk of disease progression, such as surgical intervention and acute urinary retention.

They should be offered to patients with moderate-to-severe LUTS who are at risk of disease progression and/or enlarged prostate gland.

<strong>D. Muscarinic receptor antagonists</strong>

Muscarinic or m-cholinoreceptors include five different types, M1-M5. M2 and M3 receptors are predominant in the bladder, though functionally, M3 is more important, although less numerous than M2. The parasympathetic nerve fibres in detrusor smooth muscle are stimulated by acetylcholine.

Antimuscarinics include darifenacin, fesoterodine, oxybutynin, propiverine, solifenacin, tolterodine, trospium and transdermal preparations of oxybutynin. Side-effects include dizziness, blurred vision, ocular hypertension (closed-angle glaucoma), dry mouth, constipation and urinary retention.

These agents decrease bladder strength, increase bladder capacity and increase post-void residual (PVR) volume. Although there is no evidence for a causal relationship between acute urinary retention and use of antimuscarinics, these agents should be used with caution in patients with high PVR. Similarly, in elderly patients, caution is advised, as not all antimuscarinics have been evaluated in this age group of patients.

They should be offered to patients with OAB or mixed symptoms with a predominant storage component, either as monotherapy or combination.

<strong>E. Phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors</strong>

These agents reduce smooth muscle tone of the detrusor, prostate and urethra. They work by increasing intracellular cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP). They improve oxygenation by improving blood flow and neurotransmission through the lower urinary tract and altering pathways in spinal cord.

Tadalafil 5mg once a day has been licensed for the treatment of LUTS. The side-effects include flushing, gastroesophageal reflux, headache, nasal congestion and back pain. It is contraindicated in unstable angina pectoris, recent myocardial infarction, stroke, hypotension, poorly-controlled blood pressure, significant hepatic or renal insufficiency, anterior ischemic optic neuropathy with sudden loss of vision, and cardiac failure. It is contraindicated in patients taking nitrates, potassium channel-opener nicorandil or doxazosin and terazosin.

It improves symptom score but has little improvement over maximum flow rate. Currently, it is recommended for patients with moderate-to-severe LUTS, with or without erectile dysfunction.

<strong>F. Plant extracts</strong>

These agents contain phytosterols, fatty acids, lectins and ß-sitosterol. They have anti-androgenic, oestrogenic and anti-inflammatory effects via complex pathways but effects have not been confirmed <em>in vivo</em>. The precise mechanism of action remains unknown.

These include <em>Cucurbita pepo</em> (pumpkin seeds), <em>Hypoxis rooperi</em> (South African star grass), <em>Pygeum africanum</em> (bark of the African plum tree), <em>Secale cereale</em> (rye pollen), <em>Serenoa repens</em> (saw palmetto) and <em>Urtica dioica</em> (roots of the stinging nettle).

There are conflicting reports on their efficacy, therefore there are no current clinical recommendations on their use.

<strong>G. Beta-3 agonists</strong>

β-3 receptors are present in detrusor smooth muscle cells and upon activation cause relaxation, leading to an increase in bladder storage capacity, reduced micturition frequency and urgency.

Mirabegron is a currently licensed β-3 receptor agonist, which has been studied mostly in a female study population with OAB. The side-effects include hypertension, UTI, headache and nasopharyngitis. It is contraindicated in patients with severe, uncontrolled hypertension and blood pressure should be monitored frequently while on treatment.

This agent can be used in patients with predominantly storage symptoms, either as monotherapy or with combination.

<h3><strong>Surgical treatment</strong></h3>

For the last 90 years, TransUrethral Resection of Prostate (TURP) has been the gold standard for the treatment of LUTS secondary to BOO due to BPE. Many new treatment options are available that are either equally effective or superior to TURP. Patient selection is an extremely important factor in deciding for optimum surgical treatment.

<strong>A. Electrosurgical</strong>

These methods include TUIP (TransUrethral Incision of Prostate), monopolar TURP, bipolar TURP, plasmakinetic bipolar TUVP (TransUrethral Vaporisation of Prostate) and bipolar enucleation. For smaller prostate sizes (<30ml), TUIP is indicated, whereas larger glands require resection/vaporisation or enucleation. The major difference in these various methods of treatment is the method of delivery of energy; in monopolar TURP, circuit is completed in glycine travelling through the body to reach the diathermy pad, whereas in bipolar TURP, it is completed locally via the active pole and passive pole at the tip of the working element (or the sheath) in normal saline. Plasmakinetic bipolar TUVP uses high voltage to create plasma and the gland is dealt with by ‘hovering’ the resectoscope tip over the tissue, thereby vaporising it. This method decreases the size of the coagulation zones as compared to other methods. Bipolar enucleation involves resecting the prostatic lobes, dislocating them into the bladder, converting them into smaller pieces with the help of a morcellator, and their evacuation.

By using saline as opposed to glycine as an irrigant, performing at a lower energy, bipolar methods have comparable efficacy as monopolar TURP, with reduced side-effects.

<strong>B. Laser treatment</strong>

HoLEP (Holmium Laser Enucleation of Prostate) and HoLRP (Holmium Laser Resection of Prostate) utilise holmium:yttrium-aluminium. garnet (Ho:YAG) pulsed solid-state laser is absorbed by water.

It enucleates or resects prostatic tissue and achieves haemostasis by coagulation and necrosis. It has a superior safety profile compared to monopolar TURP and is comparable to open prostatectomy in terms of long-term functional results.

‘Greenlight’ laser utilises Kalium (Potassium)-Titanyl-Phosphate (KTP) and lithium triborate (LBO) side-firing lasers, which are absorbed by haemoglobin-containing tissues, hence are ‘photoselective’. It has excellent haemostatic property and a high intraoperative safety profile. It can be offered as an alternative to monopolar TURP.

Thulium laser vaporisation and anatomical enucleation involves Tm:YAG continuous laser. Thulium VAPorisation (ThuVAP), Thulium VapoResection of Prostate (ThuVaRP) and Thulium VapoEnuncleation of Prostate (ThuVEP) have been described. They are safe and can be used in patients on antiplatelets or anticoagulation. Results are comparable to TURP and HoLEP.

<strong>C. Prostatic urethral lift (Urolift)</strong>

This is a relatively newer cystoscopic technique in which encroaching lateral lobes are kept apart via small suture-based implants. The procedure can be performed as day surgery, either under local or general anaesthetic. The downside is the large prostates and median lobe, which if present, cannot be treated effectively. There are fewer sexual side-effects and functional results are comparable to TURP in the short term.

<strong>D. Prostatic stents</strong>

These can be temporary or permanent stents, depending on epithelialisation and biodegradability. They were primarily designed as a replacement for urethral catheter. Because of high rate of migration, they have a limited role in long-term improvement of symptoms. Temporary stents have shown to provide good short-term results in patients who are awaiting intervention. Examples are Allium, Memokath and TIND (Temp Implantable Nitinol Device).

<strong>E. Prostatic artery embolisation</strong>

This is a percutaneous, minimally-invasive technique performed as a day case under sedation or spinal anaesthesia. Access is via common femoral artery to reach both prostatic arteries to be embolised. There is no correlation between gland size and associated adverse events, with preserved sexual function with modest short-term functional results.

<strong>F. Prostatectomy (open/laparoscopic/robotic)</strong>

In very large glands, adenoma can be removed either by open or laparoscopic surgery, which can be robot-assisted. The prostate can be approached through the prostatic capsule or bladder. Totally laparoscopic or robot-assisted laparoscopic approach can be either retroperitoneal or transperitoneal. HoLEP, photoselective vaporisation of prostate and bipolar enucleation, have been shown to achieve comparable rates with larger gland sizes, while maintaining significantly lower complication rates.

<h3><strong>Summary</strong></h3>

For patients with mild LUTS and low bother scores without any risk of clinical progression, reassurance and lifestyle advice should be offered.

In patients with moderate-to-severe LUTS without any evidence of risk of clinical progression, α-blockers are the first-line agents. If there is high risk of clinical progression or evidence of enlarged prostate, combination treatment with an α-blocker and 5- α-reductase inhibitor can be initiated. For patients with OAB or persistent storage symptoms, anticholinergics should be started or added to α-blocker/combination treatment. If LUTS coexist with erectile dysfunction, α-1a-blocker and PDE-5 inhibitor such as tadalafil can be beneficial.

Patients who have failed medical therapy are candidates for surgical intervention, which depends on age, availability of expertise, comorbidities, patient choice, prostate size and preservation of potency.

<strong>References on request</strong>

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.