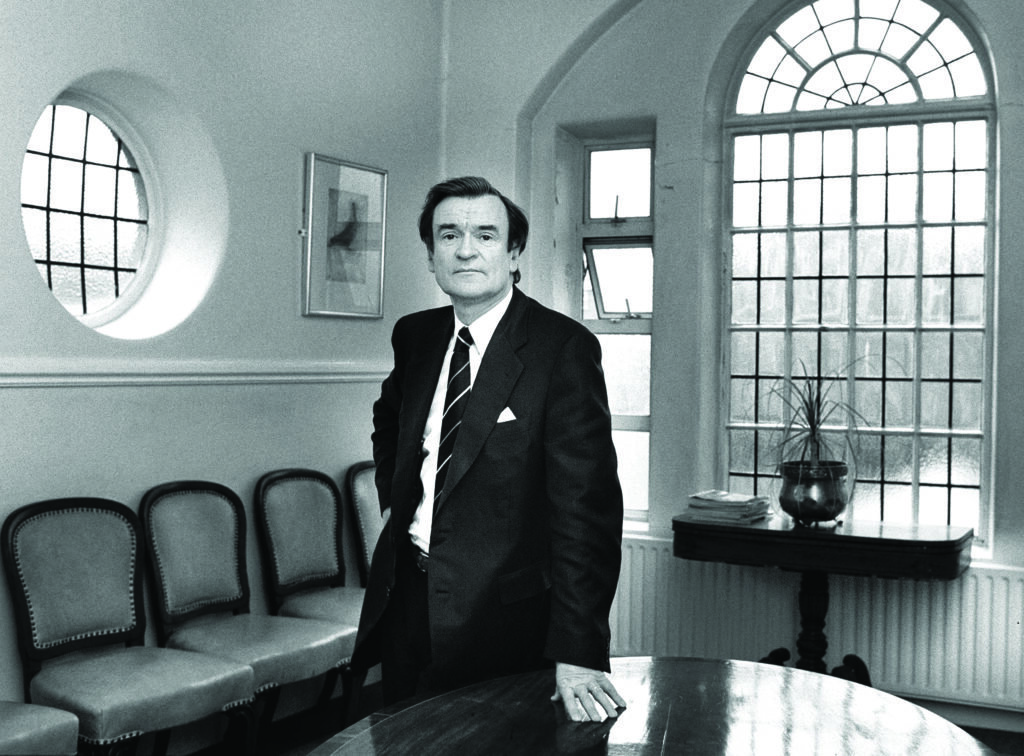

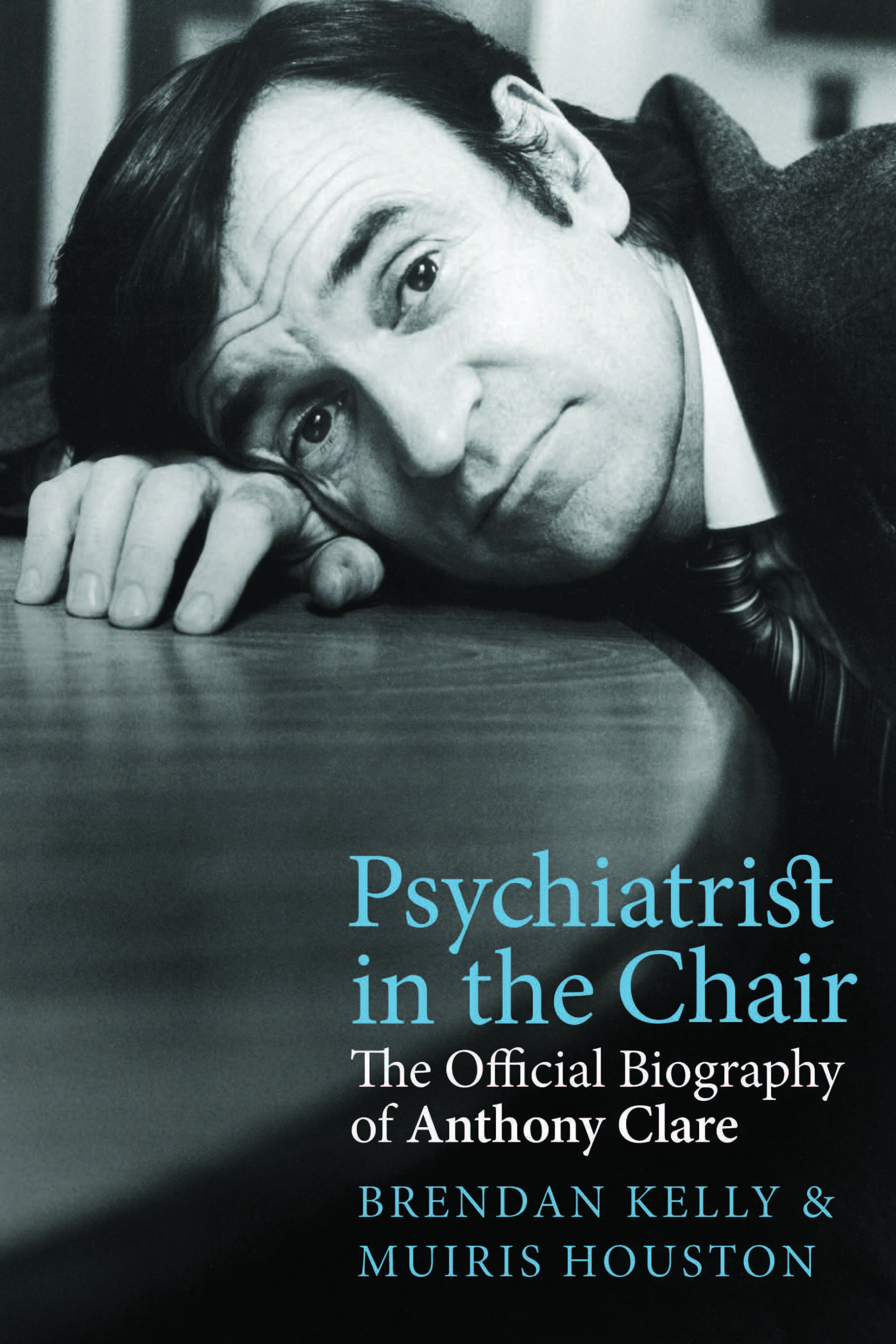

In an extract from their new biography of Dr Anthony Clare, Prof Brendan Kelly and Dr Muiris Houston write about the interviews the noted Irish psychiatrist conducted with UK politicians on his radio show

Irish psychiatrist Dr Anthony Clare achieved international fame through his interviews with prominent public figures on In the Psychiatrist’s Chair, which ran on BBC Radio 4 between 1982 and 2001. Over the course of the programme, Clare spoke with hundreds of well-known figures, ranging from Spike Milligan to Anthony Hopkins, Barbara Cartland to Joanna Lumley. The programme was produced by Michael Ember who came from Hungary to the UK in 1956 and made multiple talk-radio programmes for the BBC. In the early 1970s, Ember devised Stop the Week, a light-hearted programme that Clare appeared on and that ran for 18 years, until 1992. Ember also revived Start the Week, devised Midweek and, with Clare, co-created In the Psychiatrist’s Chair, which was probably Ember’s most iconic work. In the Psychiatrist’s Chair was originally to be titled What Makes you Tick? and its raison d’être was to reveal the real person behind the façade of celebrity. Ember had studied psychology and criminology at the University of London and shared with Clare a deep curiosity about human motivation and behaviour.

Clare described the idea for the series as a joint one that grew out of discussions between Clare and Ember over several years. In addition, Judith Jackson, who worked in the biochemistry department at the Maudsley Hospital in London, where Clare also worked, expressed an interest in knowing about the inner lives of well-known people. Following his initial interview with actor Glenda Jackson in 1982, the series featured such diverse figures as Buddhist judge Christmas Humphreys and – most famously – comedian Spike Milligan, with whom Clare would later write a book titled Depression and How to Survive It. While Clare’s engaging style quickly became familiar to listeners, the content of the interviews varied considerably from episode to episode.

Clare commonly asked why the interviewee had agreed to participate and enquired into their childhood, but beyond that there was considerable diversity, as Clare followed where the interviewee led and adapted his questions to the individual in the chair. The first season of In the Psychiatrist’s Chair proved a great success although it was clear early on that Clare revealed little of himself during the broadcasts. In 1984, Clare reflected that the series was intended to be more mutual than it turned out to be. Indeed, a 1995 review of a book stemming from the series noted that many of Clare’s brief contributions were as interesting as those of his guests. In any case, regardless of Clare’s initial reluctance to reveal much of himself, the early episodes generated a large and loyal following and ensured the continued survival of the programme over the following years. Clare elicited genuine revelations from many of his guests. Writer Carla Lane opened up quite unintentionally as she discussed her work, childhood, family, and love of animals, stating that most people who have animals say that animals are better than humans.

Prof Wendy Savage, gynaecologist, “had never met Anthony Clare” before her 1986 interview, but “knew of him, respected his work, and found him an engaging personality. It was easy to talk to him and, being a doctor, I was probably less wary of him than non-medical journalists.” In 1988, politician Edwina Currie gave a frank and moving interview, as Clare later recalled, telling him about the end of her relationship with her father. Reflecting back some 30 years later, Currie’s recollection is that Clare “wasn’t able to delve very deep, as I was practised in revealing only what I wished to”. Unlike most other guests, Currie knew Clare personally prior to the interview, from her time at the Department of Health, where she was Parliamentary Undersecretary of State for Health from 1986 to 1988. Currie had met Clare “several times and admired and liked him. To make psychiatry accessible to the general public, to talk through many issues that affect us all in a professional, but popular way, was I thought entirely praiseworthy.

We were trying at the time to improve services for people with mental illness and mental handicap, and to diminish the stigma attached to both. That’s why I was glad to work with him. He sussed out motivations that his targets had no idea they held; he made his profession sound like a constant detective story.” Currie points out that Clare was “deeply respected” in the UK and that he and Irish comedian Dave Allen “were a reminder in the grim days of the IRA [Irish Republican Army] that Ireland was not all about politics”. Like Currie, many other politicians remember their interviews with Clare. Nigel Lawson agreed to an interview with Clare in 1988 solely “because I had enjoyed his previous programmes”, even though Lawson emphatically considers himself “a very private person”.

Lawson recalls that “I told him very little and suspect that it was the most boring programme he ever made”. Lawson’s was, in fact, a fascinating interview, as was Clare’s 1997 interview with another politician, Ann Widdecombe, who, like Lawson and Currie, is skeptical about just how penetrating Clare was. Clare later described Widdecombe as a conviction politician with unmovable views on a range of issues, a theme that they explored in some depth in the interview. Reflecting today, Widdecombe comments that “there was a lack of originality to the interview. [Clare] went over ground that had already been covered extensively in press and media. Other than questions about if I would have been a good mother, he didn’t really come up with anything original. He stuck with entirely predictable ground, which made for a very relaxed interview.”

The interview with Widdecombe might have been “relaxed” for her, but it was gripping for listeners. Clare, for his part, described the encounter as good-humoured, although he felt that Widdecombe was irked at having to discuss feelings and would have preferred to have an argument about sex on television or abortion. Widdecombe recalls Clare as “very personable” and says that the process “was remarkably straightforward. I went to a very small television studio, I think it was Broadcasting House. There was just the two of us in the studio. Unlike most political interviewers, he did at least give me time to answer. I’m naturally wary of people who go in for psychoanalysis, but I enjoyed the interview. [Clare] was very personable. We chatted a bit before and a bit afterwards. He had a nice personality, and was somebody I could quite cheerfully have dinner with despite his profession.” Widdecombe recalls that, after the interview was broadcast, one of her friends said that, “listening to [Clare], she thought he simply didn’t understand belief ”.

Another friend said “she had been interested in him [Clare] rather than me [Widdecombe] during the programme”. And a political colleague “wasn’t sure a practicing psychiatrist should be doing this for entertainment”. Clare was keenly aware of potential criticism of the programme’s title from the outset and worried that some listeners might think that the series was psychiatry being practiced on the radio, with the guests as patients and the psychiatrist-presenter performing clinical analysis and possibly even therapy on the air. In the end, however, Clare felt that no other title suited and that In the Psychiatrist’s Chair was, at the very least, an honest title: After all, the interviews had a psychiatric flavour and the interviewer was undoubtedly a psychiatrist.

Over time, certain aspects of Clare’s programme evolved. Some of the emphasis shifted from the interviewee to the interviewer as the figure of Clare became more established in the public eye. From a technical perspective, Ember used quite long silences in the final edits, which was very unusual on radio, and the interviewee had no editorial control over the final edit that was broadcast. But many features remained constant. Clare’s wife Jane recalls that, after his return to Ireland in 1989, Clare would “leave St Patrick’s Hospital in Dublin with 15 minutes to spare to catch the airplane to London. He’d run off the plane, do the interview, and come back that evening.” She adds that “different people elicited a different response from Tony. Tony was a debater and could be combative. He was very good at seeing where the chink was.”

For the most part, Clare’s gamble paid off richly. As Widdecombe notes, “the programme had a very wide listenership. It was the sort of thing people would mention to me months later…. It was something that people remembered long after it took place, which is always a tribute to the interviewer or interviewee or both.” In the interview with Widdecombe, certainly, both interviewer and interviewee performed with relish and aplomb, making the recording a memorable, if distinctly odd, classic of its genre.

Extract from Psychiatrist in the Chair: The Official Biography of Anthony Clare by Prof Brendan Kelly and Dr Muiris Houston (Merrion Press, 2020)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.