Title: Catching the worm: Towards ending river blindness and

reflections on my life

Author: Prof William C Campbell, with Claire O’Connell

Publisher: Royal Irish Academy

Reviewer: Prof Seamus O’Mahony

Prof William Cecil Campbell is the only Irishman to have been awarded the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine. He and Satoshi Ōmura shared the award in 2015 with the Chinese malaria researcher Youyou Tu. Campbell and Ōmura were cited “for their discoveries concerning a novel therapy against infections caused by the roundworm parasites”. That novel therapy was ivermectin and the infection was river blindness. Campbell was 85 when he won the Nobel, having worked for most of his career in the US with the pharmaceutical company Merck. Catching the Worm – co-written with the Irish science writer Claire O’Connell and published by the Royal Irish Academy – is Campbell’s memoir, launched on the occasion of his 90th birthday, June 28, 2020.

Campbell grew up in Ramelton, Co Donegal: “Both of my parents were from backgrounds of Protestant farmers, a population historically common in the northern part of Donegal – plain-spoken, hardworking, abstemious people.” His family must have been well-off, as the children had a private tutor, “Miss Martin”, and followed on to boarding school in Belfast. After taking a first in zoology at Trinity College Dublin, Cecil Campbell went on a Fulbright scholarship to Madison Wisconsin to undertake doctoral research. On the boat to America, he decided that henceforth, he would be ‘Bill’. “I had grown to dislike the name Cecil.”

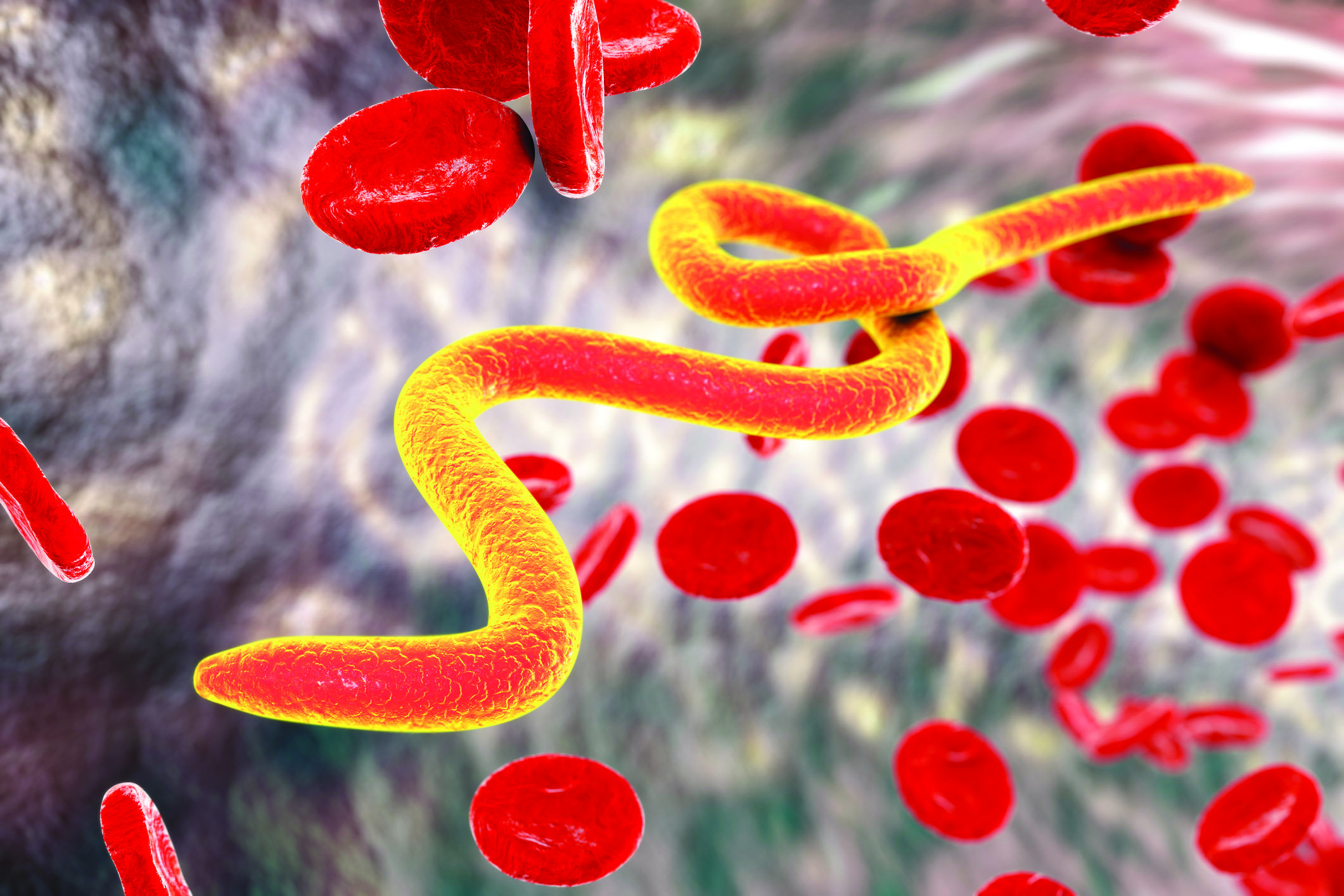

Having completed his PhD on liver fluke in 1957, he got a job at Merck’s headquarters in New Jersey and stayed with the company for the next 33 years. He joined their parasitology division and worked on schistosomiasis, liver fluke, potato blight, and roundworms. Ivermectin was an empirical discovery. Satoshi Ōmura, a Tokyo-based microbiologist, isolated soil-based bacteria from the Streptomyces group, one of which produced a substance with anthelmintic properties. Campbell headed up the team at Merck that characterised and synthesised this substance, which was named ivermectin. Campbell knew that horses were commonly infected with a parasitic worm called Onchocerca; a colleague at Merck found that ivermectin was effective against this parasite, which prompted Campbell to wonder if the drug might work against another species of Onchocerca – Onchocerca volvulus – which causes river blindness in humans. The parasite has infected many millions of people and causes blindness by a glaucoma-like process.

“After much planning,” writes Campbell, “the first river blindness trial took place in Dakar, Senegal, in 1981.” This first small trial produced encouraging data. An industry-public partnership was established, involving Merck, the World Health Organisation and the World Bank. The Mectizan Expert Committee of tropical medicine experts was established, along with the Mectizan Donation Programme (the human formulation of ivermectin was called Mectizan). The former US defense secretary Robert McNamara was then president of the World Bank and personally backed the initiative, as did ex-US President Jimmy Carter through his Carter Foundation. Thirty years on, more than three billion people have been treated with ivermectin. River blindness has been eradicated in Central and South America and vastly reduced in Sub-Saharan Africa. Campbell writes: “It has been, and continues to be, an undertaking of colossal commitment in areas of science, corporate responsibility, public health management, international and inter-agency cooperation, communication, and good will. It was built on the heroic tropical field-work of those who established the human safety and effectiveness of the drug. It was an undertaking that led to a transformation in individual lives.”

Addressing the accusations that Merck gave away the ivermectin for tax breaks, or as a cynical exercise in corporate morale-boosting, he writes: “The actual tax benefits in this case are, I am told, negligible… I believe that Merck employees felt proud because they believed the company had done the right thing; and furthermore they believed that the company had done the right thing because it was the right thing.” Catching the Worm is, in parts, a trifle dull, but Campbell’s integrity shines through; his account of the river blindness programme reminds us what can be achieved when pharma companies and global health agencies work together.

Merck’s story since that triumph has not been a glorious one, with several scandals, the most notable being Vioxx, for which the company was fined nearly $1 billion. I have been a vocal critic of Big Pharma, but even I had to salute the Mectizan Donation Programme. I had to salute too, this humble, self-effacing man, who was genuinely surprised when he was phoned by a journalist who told him that he had won the Nobel Prize. He is at pains to point out that the discovery was the result of teamwork and attributes his award to the “Matthew effect” (a phrase coined by the sociologist Robert Merton), referencing the maxim from the Book of Matthew that “For whoever has, to him more shall be given”, meaning that “scientists with many honours tend to accumulate further honours at a higher rate than do scientists with few honours”.

Campbell writes that ivermectin is an example of empirical research and laments the move away from this approach to what he calls “the rational approach”, driven by advances in molecular biology: “We belittle and ignore the empirical approach at our peril.” Campbell is an exemplar of traditional scientific values. In the epilogue, he concludes: “In science, doubt is our stoutest ally.”

Dr Seamus O’Mahony is the author of Can Medicine Be Cured? The Corruption of a Profession (Apollo, 2019)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.