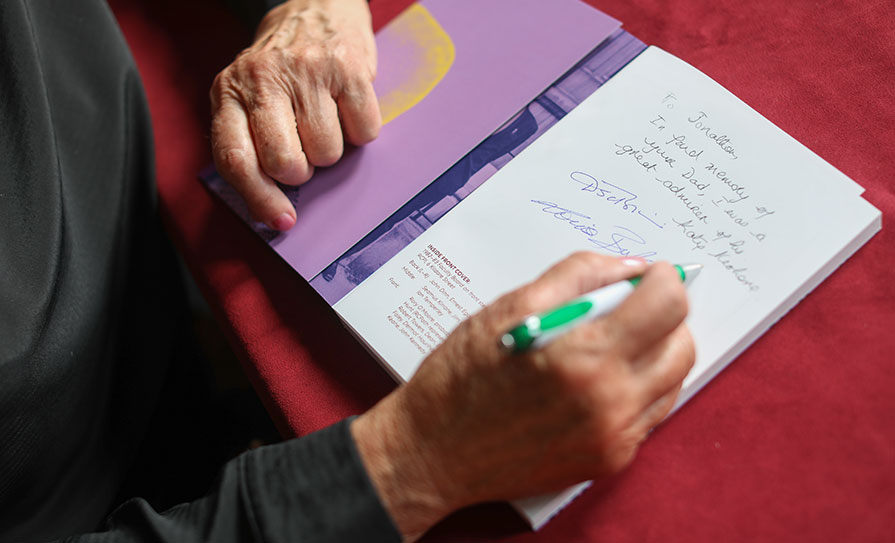

‘Faculty of Pathology 1981–2021: A History of the Faculty and Pathologists in Ireland’ explores the development of the specialty and the people who drove it forward. Below are extracts from the book, which marked the Faculty’s 40th anniversary.

This book came about from the Dean’s approach to the Vintage (retired) Pathologists group in March 2020 for ideas to commemorate the Faculty of Pathology’s 40th anniversary. The group heartily supported the idea of a book and made major contributions to its contents. It is an account of the Faculty of Pathology’s development over the past 40 years, against the background of the earlier development of pathology in Ireland. The chapters deal with Faculty activities especially in education, training, standards and quality assurance, increasing pathology consultant and training posts, the change from general pathologists overseeing all branches of laboratory medicine to the establishment of training programmes and recognition of six approved specialties in clinical microbiology, chemical pathology, haematology, histopathology, immunology, and neuropathology.

Chapters also cover regional development of pathology within Ireland, Faculty Deans and officers, and the Vintage Pathologists. A culture and heritage section includes a review of the autopsy report on the leading Republican Thomas Ashe in 1917, an account of the life of Charles Donovan who spent much of his childhood and medical student days in Cork and Dublin and made major discoveries in infectious diseases in India, and items of interest from the Royal College of Physicians of Ireland Archives.

The contrasts between the Faculty at its inception in 1981 and 40 years later are striking, reflecting the change in scale of Faculty business. The first Annual Report in 1982 was a typewritten A4 page-and-a-half, while recent Annual Reports stretch to an average of 40 pages, almost books in themselves. An early financial report read “The Faculty’s finances are healthy”; recent financial reports run to several pages of detailed audited figures of income and expenditure.

In this book there is an emphasis on identifying the earlier pathologists and including a flavour of their personalities and work practices. Some of our predecessors worked under difficult conditions, despite which they made progress. It is notable how they absorbed every increase in hospital and laboratory activity, without corresponding staff support. Outside the major cities, single-handed general pathologists also provided a post-mortem service for coroners across many counties. Some pathologists describe vividly their primitive working conditions, from which great advances were made in laboratory, clinical and scientific services. This book acknowledges their contributions, which should not be forgotten.

Extracts from Pathologists and Histopathologists in Dublin 1750-2020

Pathology developed in Dublin from the 1750s when Samuel Clossy described his autopsy findings in a series of patients who had died at Dr Steeven’s Hospital. In the mid-1800s the Pathological Society of Dublin met every Saturday afternoon over a 40-year period and by the late 1800s the first professorships of pathology were established. Diagnostic pathology began by the early 1900s when most hospitals had a single general pathologist, sometimes with an assistant, and in the latter half of the century consultant posts in the specialties of histopathology, microbiology, haematology, clinical chemistry, and immunology emerged, structured training for pathologists and clinical scientists was introduced and staff numbers increased substantially.

Pathologists who studied tissue, either from surgical excisions or at autopsy, were variously called anatomic pathologists, morbid anatomists or histopathologists (a term introduced in about 1895 to indicate the histological study of abnormal or diseased tissue). The discipline included surgical pathology and the autopsy areas of forensic pathology and hospital or consented autopsy.

Early subdivisions included neuropathology and paediatric or neonatal pathology; while further subdivision such as renal pathology or dermatopathology came later. Histopathologists, the lineal descendants of the early (general) pathologists, were the most numerous pathologists, and often in the smaller hospital they maintained elements of the role of the general pathologist until the early 2000s.

Some of the earliest pathologists focused on bacteriology, and others, many with scientific rather than medical training, practiced clinical biochemistry. Specialists in haematology and blood transfusion only became numerous after the middle of the 20th Century and immunology came later. As pathology became more complex in the late 20th century specialists in the areas of microbiology, clinical chemistry, haematology and immunology were appointed in all the larger hospitals and completely replaced the general pathologist.

In this book there is an emphasis on identifying the earlier pathologists and including a flavour of their personalities and work practices

The number of local hospitals complicates the history of pathology in Dublin. The Hospitals Commission, appointed to advise on hospital distribution and staffing in the new Irish state (and to distribute Irish Hospital Sweepstakes money), wryly recorded in its first report in 1933-4: “Amongst the deficiencies of the Dublin General Hospital system, there cannot be included that of scarcity of numbers.” The report listed 25 hospitals, 12 general hospitals, and 13 special hospitals and noted that a commission from 1854 had recorded a similar number of hospitals.

The first Chair of pathology in Ireland was established in 1856 at the new Catholic Medical School, founded by Cardinal Newman, and forerunner of University College Dublin Medical School. The first holder was Robert Spencer Dyer Lyons (1856-1886) who had studied fevers in the British troops in the Crimea by autopsy and histology, and had become an expert on yellow fever.

However, he was also the Professor of Medicine as was his successor as Professor of Pathology, Christopher J Nixon (1887-1891), and it was not until 1891 with the appointment of Edmond J McWeeney (1891-1925) to the post, renamed Professor of Pathology and Bacteriology, that a full-time pathologist was in post.

McWeeney had studied bacteriology in Berlin under Robert Koch. “He was a leader in bacteriological teaching and the first person to demonstrate tubercle bacilli in the sputum in Ireland.”

Until well into the second half of the 20th Century many hospitals maintained a strong religious ethos. Haematologist Ian Temperley has described how in Trinity College and its associated hospitals the staff was predominantly Protestant. In contrast the staff at University College Dublin and the Mater and St Vincent’s Hospitals was almost exclusively Roman Catholic. Gender imbalance was even more profound. There were no woman pathologists listed until the 1950s. Joan Marie Mullaney was at the Meath Hospital (1956-1966), Reader in Pathology at Trinity College Dublin from 1957, Consultant at Mercer’s Hospital in 1962 and later at the Royal Victoria Eye and Ear Hospital.

Extracts from Pathology Development in the South (Munster) Region

In the late 19th and early 20th Centuries, doctors were ‘multi-specialist’, having a clinical role and additionally conducting diagnostic tests and autopsies. Pathology was not a recognised specialty, but several notable doctors in Cork lectured in medical jurisprudence. Charles Yelverton Pearson lectured in anatomy, became Professor of Materia Medica (roughly equivalent to therapeutics), and held the Chair in Surgery. He became quite famous for conducting a post-mortem on an exhumed body, the wife of a doctor suspected of being poisoned by her husband. As far as can be determined, the first Professor of Pathology in University College Cork (UCC) was Arthur E Moore (1909–1940), a graduate of UCC. He studied pathology in Vienna and Prague. Moore built up an extensive teaching museum, lectured around the south of Ireland in the anti-tuberculosis campaign organised by Lady Aberdeen, and acted as extern examiner in pathology in RCSI. He was succeeded by William J (Billy) Donovan, appointed in 1941, also Consultant Pathologist to the South Infirmary Hospital, Cork. The North and South Infirmaries in Cork city were the major public hospitals and sites for teaching medical students and training doctors.

In the 1960s following several key professorial and consultant appointments, St Finbarr’s Hospital on Douglas Road became the largest teaching centre for the region. St Finbarr’s had been the former Cork County Home and Workhouse, and the buildings dated from 1841. Because of its history, being admitted to the hospital was feared by older Cork people. “Please don’t send me to the workhouse Doctor. No one ever comes out of there!” was a common plea, and it took many years to allay those fears. In the 1960s the laboratories were in prefabricated buildings (a common feature in many parts of Ireland). The academic department was on the west side of the UCC main university campus, where all lectures, practical classes and examinations were held. In 1975 with funding from the Irish Cancer Society, Cuimín Doyle, Professor of Pathology at UCC, collaborated with Professors Michael P Brady (surgery), Aidan Moran (statistics), and John Corridan (epidemiology), in setting up the Southern Tumour Registry, which produced its first annual report in 1976. It was the forerunner of and subsumed into the National Cancer Registry in 1991.

St Finbarr’s staff moved to the newly constructed Cork Regional Hospital in Wilton (now Cork University Hospital – CUH) on the west side of the city in November 1978, followed by the pathology departments in January 1979. The hospital was regarded as very luxurious compared with the historic old SFH limestone buildings and was nicknamed ‘the Wilton Hilton’ by locals. The academic pathology department moved from the main UCC campus to the new hospital later that year. All teaching was done at CUH.

CUH was involved in managing the aftermath of three major disasters, which had significant consequences for all the pathology departments. The Whiddy Island Oil Disaster, Bantry, occurred in January 1979 when an oil tanker (the Betelgeuse) exploded resulting in 51 deaths (all on board the vessel and one visitor, as well as eight employees of the Whiddy terminal, and one diver involved in raising the vessel). Raymond O’Neill headed the forensic pathology investigations on those bodies which were recovered. The victims were brought to the new post-mortem room at Cork Regional Hospital.

The Buttevant Train Accident on the August bank holiday in 1980 involved the Dublin-Cork train and resulted in 18 deaths. More than 70 people were injured, and most were in the front first class carriage. The carriages had wooden frames which collapsed. Post-mortems were carried out by the pathologists in CUH.

The Air India Disaster occurred in June 1985 when a passenger flight from Toronto to London exploded in the air, resulting in the loss of 329 passengers and crew. Most of the victims were Canadian citizens. Post-mortems were carried out on 131 bodies recovered from the sea 190km off the southwest coast. The logistics of identifying the remains, dealing with grieving relatives, storing the bodies in specialised refrigerated trucks, and converting a large hall into a temporary post-mortem room were difficult. A forensic investigation was required and the subsequent investigations by the Canadian government concluded that the plane was bombed by Canadian Sikh terrorists.

Faculty response to major issues of public interest

Contamination of blood and blood products by infectious organisms such as HIV and hepatitis C. These problems were not unique to Ireland and were also experienced in many other countries. The contamination led to death and serious injury. There were several investigations which led to the Report of the Expert Group on the Blood Transfusion Service Board (1995) and The Lindsay Tribunal. Following these, the Irish Blood Transfusion Service was relocated in a purpose-built premises on an acute hospital site, the National Haemovigilance Office was instituted with the development of haemovigilance throughout the country and in line with the Comhairle na n-Ospidéal report on Haematology Services more consultant haematologists were appointed. From November 2005 the reporting of serious adverse reactions to the administration of blood and blood products and testing, storage, and distribution of same has been mandatory.

Organ retention – The Irish component of this controversy followed on from issues at the Bristol Royal Infirmary and the Royal Liverpool Children’s Hospital, Alder Hey, in the UK in the late 1990s. This resulted in the establishment of the Dunne and subsequent Madden Inquiries. The Faculty made submissions to each and met with the Chairs of both Inquiries and the Ministers of Health. The Faculty produced guidelines for post-mortem procedures for coroners and non-coroners’ post-mortems and an explanatory document for the relatives of the deceased. The media coverage was extensive and there was an impact on the perception, number and extent of post-mortems. The post-mortem rate for non-coroners’ cases fell dramatically from 30 per cent to 2 per cent in some hospitals. The educational value to clinicians, medical students and pathologists in training was lost, as well as a valuable quality assurance tool.

Hospital-acquired infection – There is increasing public awareness of hospital-acquired infections such as MRSA and ‘superbugs’ with their associated morbidity and mortality, resulting in national hygiene audits of hospitals and the introduction of national standards. The important role of the infection control team including consultant microbiologists has been highlighted.

Misdiagnosis in cancer cases – Against the background of widely publicised misdiagnosis in breast cancer, and a HIQA inquiry, Faculty met with Tom Keane, Director of the National Cancer Control Programme (NCCP), in 2008. Priority areas included restoring public confidence in pathology and cancer diagnostics, measures to monitor and improve quality of pathology services, accreditation of pathology services, and competence assurance measures. The Faculty addressed these areas, leading to the development of the National Histopathology Quality Improvement Programme.

Outsourcing of cervical cytology

In response to the decision to outsource cervical screening cytology by the National Cancer Screening Service (NCSS) to Quest Diagnostics in the USA, a sub-committee was instituted by a Faculty Extraordinary General Meeting (EGM) on 26 June 2008. Concerns raised included the loss of a valuable national resource and the wider implications for laboratory medicine in general, arising from this action of Government. Despite strong representation to Government by the Faculty, most laboratories were instructed to ‘cease and desist’ their cervical cytology screening service.

Covid-19

Pathologists, in particular our microbiology/virology colleagues, played a significant role in the pandemic response at local, Faculty and Governmental level. Faculty Fellows contributed to this national healthcare response through national and other committees/roles including: National Public Health Emergency Team (NPHET), Expert Advisory Group (EAG), Covid-19 Mortality National Co-ordination Group (Faculty post-mortem guidelines were published), National Transfusion Advisory Group (NTAG) and the Medical Leaders Forum (convened in response to the Covid-19 pandemic and which brought together postgraduate training bodies, leaders in the clinical community, the HSE and Department of health). The Faculty worked in collaboration with the National Clinical Programme in Pathology (NCPP) to host regular online meetings with laboratories regarding testing for Sars-CoV-2 and meetings with the Irish National Accreditation Board (INAB) regarding remote laboratory assessments. To ensure continuity of Faculty business and educational activities, there was rapid adaptation to the utilisation of online resources.

Faculty of Pathology 1981 – 2021: A History of the Faculty and Pathologists in Ireland is edited by Prof Katy Keohane, with the support of the editorial board, Prof Sean O’Briain, Ms Harriet Wheelock, and Prof Louise Burke. Minor edits to the above extracts have been made by the Medical Independent.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.