An overview of the latest treatment and diagnostic approaches to overactive bladder

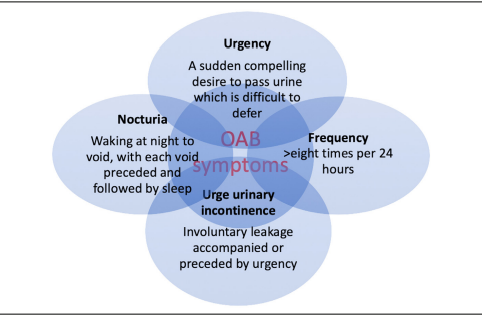

Overactive bladder (OAB) syndrome is a chronic disabling condition that significantly reduces the quality-of-life of millions of people worldwide. The International Continence Society (ICS) defines OAB as “urinary urgency, usually accompanied by frequency and nocturia, with or without urgency urinary incontinence (UUI), in the absence of urinary tract infection (UTI) or other obvious pathology”.

OAB affects approximately 350,000 people aged over the age of 40 in Ireland. Although the condition is more common in adults over the age of 40, it can also affect children and young people. The prevalence of OAB increases with age, affecting up to 17 per cent of the population over the age of 18, and 30 per cent of those over 65 years of age.

OAB can impact significantly on quality-of-life and is responsible for several other comorbidities, including falls and fractures, depression, and increased risk of admission to hospitals and nursing homes.

The symptoms of OAB include urgency, frequency, nocturia and UUI, and many patients experience combinations of these symptoms. UUI is more common in women, and urgency and frequency more common in men.

The diagnosis of OAB can be challenging due to the lack of a specific diagnostic test and the overlap of symptoms with other lower urinary tract disorders.

Diagnosis

The definition of OAB has undergone changes over time, and currently the most commonly accepted definition is that of the International Consultation on Incontinence Research Society (ICI-RS): “Overactive bladder syndrome is characterised by urinary urgency, with or without UUI, usually with increased daytime frequency and nocturia, if there is no proven infection or other obvious pathology.” OAB can also be associated with detrusor overactivity on urodynamic testing.

The evaluation of OAB should include a detailed medical history, physical examination, and laboratory tests to exclude other causes of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) such as UTI, bladder stones, or malignancy. Dipstick urinalysis should be carried out, and a sample may also be sent to the lab to rule out haematuria, infection, and glycosuria, which could indicate the presence of diabetes. Blood tests including levels of creatinine and glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) can also provide additional information.

A detailed medical history can highlight possible risk factors for OAB. The history should focus on voiding and LUTS, the severity of symptoms and their impact on the patient’s quality-of-life. Symptom questionnaires can be used to highlight the impact of the condition on quality-of-life and to determine whether the patient requires treatment. There are numerous validated questionnaires available, however, they are not widely used.

Examination should include assessment of urinary, gynaecological, and neurological systems. A focused clinical examination can highlight risk factors and pre-existing conditions and should include an abdominal examination, digital rectal examination of the prostate in males and a vaginal examination in females. Abdominal palpation and vaginal examination enables identification of a palpable bladder and prolapse or pelvic mass in females. Symptoms of OAB in men are often attributed to bladder outflow obstruction resulting in misdiagnosis and delays in treatment. A digital rectal exam is imperative to rule out the presence of prostatic hypertrophy, malignancy, and poor rectal tone. Neurological causes of OAB can include spinal cord injury, myelodysplasia, or multiple sclerosis. Out-ruling neurological causes is important, as these patients may be at risk of upper tract deterioration/renal failure.

A voiding diary is a useful tool for assessing the frequency and volume of voids, urgency, and episodes of urge incontinence. Uroflowmetry can assess voided volume, flow rate, and post-void residual urine volume. Cystoscopy and urodynamics are usually not necessary for the diagnosis of OAB, but may be helpful in selected cases, such as when there is suspicion of bladder outlet obstruction or neurogenic bladder.

Treatment and management of OAB

Treatment and management of OAB is based on a stepwise approach, including lifestyle modifications, behavioural therapy, pharmacotherapy, and in selected cases invasive therapy.

First-line treatment is lifestyle modification, including bladder training exercises, pelvic floor exercises, and fluid management strategies. Bladder training exercises involve gradually increasing the time between voiding to increase bladder capacity and reduce urgency. Pelvic floor exercises aim to strengthen the pelvic floor muscles, which can improve bladder control and reduce urinary incontinence. Fluid management strategies include reducing caffeine and alcohol intake, as these can irritate the bladder and exacerbate OAB symptoms. Reduction in fluid intake by 25 per cent may help improve symptoms of OAB but not UUI. Advice on fluid intake should be based on 24-hour fluid intake and urine output measurements. Patients should be advised that fluid intake should be sufficient to avoid thirst and that an abnormally low or high 24-hour urine output should be investigated. If overweight, weight loss is encouraged as weight loss has a significant positive effect on leakage. Patients should also be advised to stop smoking if applicable and increase dietary fibre to avoid constipation.

Pharmacological therapy is often required when lifestyle modifications are ineffective or insufficient. Antimuscarinic drugs are the first-line pharmacological treatment for OAB. These drugs work by blocking the muscarinic receptors in the bladder, reducing detrusor muscle contractions, and increasing bladder capacity. There are several antimuscarinic drugs available, including oxybutynin, tolterodine, trospium, solifenacin, darifenacin, and fesoterodine. The choice of drug depends on the patient’s individual characteristics, including age, comorbidities, and medication interactions. Absolute contraindications to anticholinergic use include urinary retention, gastric retention, uncontrolled narrow-angle glaucoma, and known hypersensitivity to the individual drugs or their ingredients. Elderly patients should be monitored for drug interactions or polypharmacy of drugs with anticholinergic effect, ie, antidepressants, antipsychotics, anxiolytics, as the overall anticholinergic load is associated with confusion, falls, and fractures.

Mirabegron is a β3-adrenoceptor agonist with a mechanism of action that is distinct from anticholinergics. It has a lower risk of adverse effects compared to antimuscarinic drugs, although it is associated with hypertension and tachycardia in some patients and is considered as a second-line therapy when patients are intolerant to anticholinergics.

Desmopressin (a synthetic analogue of vasopressin that reduces urine production) treatment may improve nocturia and urgency episodes. Desmopressin improves quality of sleep by prolonging the period of sleep until the first void and is shown to have an acceptable safety profile in certain patients with OAB. If medications are not effective, intravesical Botox injections are another option. Intravesical botulinum toxin A prevents acetylcholine release at the neuromuscular junction, resulting in temporary chemo denervation and muscle relaxation for up to six months. The technique places multiple injections under cystoscopic guidance directly into the detrusor. Complete continence can be achieved in 40-to-80 per cent of patients, and bladder capacity improved by 56 per cent for up to six months. Maximal benefit is achieved between two and six weeks, maintained over six months. The injections can be repeated when required according to the degree of improvement or relief of symptoms.

Surgical intervention may be required in severe cases of OAB that are unresponsive to pharmacological therapy. Sacral nerve stimulation (SNS) is a surgical technique that involves implanting a device that delivers electrical impulses to the sacral nerves, which regulate bladder function. SNS is associated with risks including infection, device malformation, and nerve damage, and patients should be fully informed of the benefits and risks before undergoing the procedure. Current indications for SNS include refractory urge incontinence, refractory urgency and frequency, and idiopathic urinary retention.

More radical treatments include augmentation cystoplasty; an operation to enlarge the bladder and allow it to hold more urine, by attaching a piece of the body’s own tissue (usually from the bowel) to the bladder, and urinary diversion; which involves rerouting the ureters. This allows the bladder to be bypassed and the ureters to be routed directly to the outside of the body, allowing urine to be collected in an ostomy bag worn on the abdomen. Urinary diversion should be considered only when conservative treatments have failed, and if SNS and augmentation cystoplasty are not appropriate or unacceptable to the patient.

Emerging therapies

PDE1 and PDE5 inhibitors have demonstrated improvement in urodynamic parameters, however, PDE5 inhibitors are not currently approved for OAB. Percutaneous radiofrequency neurotomy has demonstrated feasibility in patients with neurogenic detrusor overactivity secondary to spinal cord injury, with significant improvement in patient symptoms scores. However, there is currently no evidence that transurethral radio frequency improves patient-reported symptoms of incontinence.

Support for people with OAB

Useful information and support for people in Ireland living with OAB is available at www.oab.ie, and the Continence Foundation of Ireland (CFI) website: www.continence.ie/.

References on request

Theresa Lowry-Lehnen, RGN, PG Dip Coronary Care, RNP, BSc, MSc, PG Dip Ed (QTS),

M Ed, Clinical Nurse Specialist and Associate Lecturer, South East Technological University

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.