Haematuria is one of the most common reasons for referral to a urologist and is a frequent reason for patients to consult GPs. Most urologists worldwide follow guidance set out by two international societies: The American Urological Association (AUA) and the European Association of Urology (EAU).

Both provide robust and detailed guidelines on the management of urological cancers, as well as non-malignant conditions, but only the AUA provides specific guidance on the investigation of microscopic haematuria. There are numerous causes for haematuria, including urothelial cancer, kidney cancer, urinary tract infections, and intrinsic renal disease, and clear pathways are needed to identify patients with malignant urological conditions in a time sensitive manner.

The DETECT study reported that 13 per cent of patients with visible haematuria were found to have a urologic malignancy, compared to 3.1 per cent with microscopic haematuria. Bladder cancer was found in 13.7 per cent participants in this study, with kidney cancer found in 1.8 per cent and upper tract urothelial cancer in 0.8 per cent cases.

Most guidelines recommend direct visual evaluation of the bladder with cystoscopy as part of the investigation of haematuria, but evaluation of the upper tract continues to be a source of debate worldwide.

The two main strategies for upper tract imaging in haematuria are renal ultrasound and CT urography (CT urogram). CT urogram is more costly than ultrasound and involves ionising radiation and intravenous contrast, but it is more accurate in ruling out upper-tract urothelial cancers, as it can detect subtle filling defects in the upper-tract. The updated guidance on choice of upper-tract imaging is one of the biggest changes in the new AUA guidelines.

Changes to the AUA microscopic haematuria guidelines

The AUA continues to recommend in its revised 2020 guidelines that clinicians do not rely on dipstick haematuria alone, but that a positive urine dipstick should prompt microscopic evaluation. Microscopic haematuria should be defined as the presence of ≥three red blood cells per high-power field (RBC/HPF) on a properly collected sample.

The AUA also continues to emphasise that haematuria in patients taking anticoagulant or anti-platelet agents should be investigated in the same manner as for patients not taking those agents. A systematic review of over 175,000 patients found that urologic malignancy was found in 24 per cent patients on anticoagulant/anti-platelet agents who presented with haematuria.

The 2012 AUA guidelines for microscopic haematuria recommended cystoscopy for all patients with risk-factors for urological malignancy regardless of age, all patients above the age of 35, and cystoscopy for patients under the age of 35 ‘at the physician’s discretion’.

It recommended CT urogram as the imaging modality of choice, due to its high sensitivity and specificity for detecting upper tract abnormality. The 2012 guidelines listed MR urography or retrograde pyelography (which requires a general anaesthetic) as alternative upper-tract imaging modalities for those with contraindications to contrast-enhanced CT scan. Ultrasound was not recommended in the 2012 guidelines, except in combination with retrograde pyelography for patients contraindicated for contrast-enhanced CT and MRI.

Haematuria risk stratification

In the updated 2020 guidelines for microscopic haematuria, the AUA emphasises investigation based on risk stratification for each individual patient, recognising that patients presenting with haematuria are a highly heterogenous group with differing levels of risk for underlying urological malignancy.

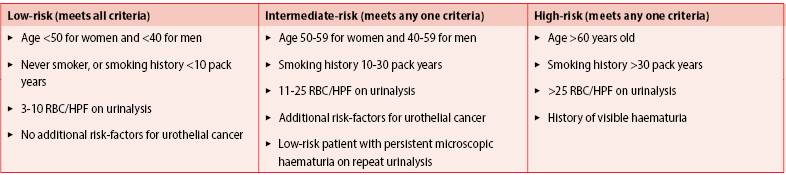

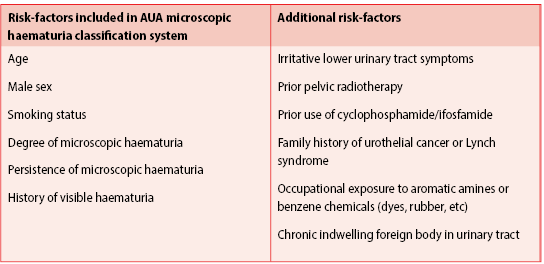

This patient-centred approach stratifies patients into low-, intermediate-, or high-risk for urological malignancy, based on the presence of risk-factors including sex, age, smoking history, history of visible haematuria, and quantification of haematuria on urine microscopy (Table 1). Investigations are then tailored on the basis of risk category.

In order to meet the low-risk criteria, patients must be aged <50 years for women and <40 years for men, have never smoked or have a smoking history totalling <10 pack years, and have three-10 RBC/HPF on microscopy, with no additional risk-factors for urologic malignancy (Table 2).

Intermediate-risk patients are classified as those who meet any of the following criteria; age 50-59 years for women or 40-59 years for men, 10-30 pack year smoking history, 11-25 RBC/HPF on urine microscopy, patients with additional risk-factors for urothelial malignancy, or those previously classified as low-risk with persistent microscopic haematuria on repeat urinalysis. High-risk patients are those aged above 60 years old, those with a >30 pack year smoking history, patients with >25 RBC/HPF on urinalysis or patients with any history of visible haematuria.

For patients deemed low-risk of urological malignancy, the AUA recommends investigation with cystoscopy and renal ultrasound, or repeating urinalysis within six months. They recommend shared decision-making between patient and physician to determine which option should be pursued for each patient.

The option to defer investigation until microscopic haematuria is deemed persistent reflects the low-risk of urological malignancy in this cohort of patients. Low-risk patients who elect to undergoing repeat urinalysis within six months and are found to have persistent microscopic haematuria should be re-classified as intermediate- or high-risk.

Intermediate-risk patients should proceed with investigation by cystoscopy and renal ultrasound. The panel again notes the overall low-risk of malignancy in patients presenting with microscopic haematuria and the need to balance the risks of ionising radiation and potential false-positives as reasons to reserve CT urogram for high-risk patients.

Patients deemed to be at high-risk for urological malignancy should be investigated by cystoscopy and CT urogram, if there is no contraindication to this. The AUA recommends MR urography for patients in whom contrast-enhanced CT is contraindicated (by poor renal function or contrast allergy). If both contrast-enhanced CT and MRI is contraindicated, retrograde pyeloureterography can be used in conjunction with non-contrast CT or renal ultrasound.

For patients with persistent or recurrent microscopic haematuria, previously investigated with ultrasound, the AUA recommends that additional imaging can be considered.

Urine cytology

The guidelines continue to advise against the use of urine cytology in the initial workup of haematuria. They conclude that there is insufficient evidence for the use of cytology or other urine biomarkers in the evaluation of haematuria. However, they do state that urine cytology may be considered for patients with persistent microscopic haematuria with negative investigations and irritative urinary symptoms or risk-factors for carcinoma in situ.

Special populations with microscopic haematuria

Another addition to the 2020 guidelines is the inclusion of a statement on patients who are at risk of renal cell carcinoma (RCC). It is recommended that patients who have microscopic haematuria with a family history of RCC, or a known genetic renal tumour syndrome, undergo upper tract imaging, regardless of their risk category.

Genetic renal tumour syndromes include von Hippel-Lindau syndrome, Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome, hereditary papillary renal cancer, hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer, and tuberous sclerosis. AUA states that there is insufficient evidence to recommend a preferred imaging modality for those with a genetic risk for RCC and this is left to physician discretion.

Irish context for guidance

A recent analysis of Irish GP referrals to a urology clinic in a Model 3 hospital found that up to 20 per cent of referrals were for investigation of haematuria. The National Cancer Control Programme (NCCP) and National Clinical Programme in Surgery (NCPS) have developed a standardised rapid access haematuria pathway, with a ‘one-stop’ clinic for visible haematuria and this is currently being piloted at Roscommon University Hospital.

The haematuria clinic allows patients to attend for clinical review and examination, with same-day cystoscopy and upper tract imaging, a system which is in place already in several hospitals in Ireland. The NCPS have drafted a proposed national standardised referral form, similar to standardised referral to the Rapid Access Prostate Clinics.

As the proposed rapid access haematuria pathway focuses on visible haematuria, clear guidance will be needed in the future for safe and cost-effective investigation of non-visible haematuria in the community and the hospital setting.

Key messages from the 2020 AUA guidelines on microscopic haematuria:

- Microscopic haematuria should not be defined by dipstick testing alone.

- A positive urine dipstick for blood should prompt microscopic examination, where microscopic haematuria is defined as >three red blood cells per high powered field on direct microscopy.

- Patients taking anticoagulant/antiplatelet agents should be investigated in the same manner as those not taking these agents.

- Patients should be investigated according to their risk category – consider deferring investigation and repeating urinalysis at an interval for low-risk patients.

- Low- and intermediate-risk patients can safely be investigated with renal ultrasound, allowing CT urogram to be reserved for high-risk patients.

- A history of painless visible haematuria automatically puts patients in a high-risk category.

References on request

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.