The main aim of care for these patients should be to minimise symptoms and prolong quality-of-life

Malignant pleural effusion (MPE) is a common complication of malignancy, affecting up to 15 per cent of individuals with cancer. It generally represents advanced or metastatic malignancy and as such the prognosis is poor, with a median survival of three-to-12 months.

Treatment is palliative in nature, with the primary aim of treatment being symptom resolution and improved quality-of-life. Additionally aiming to avoid repeated interventions or hospital admissions.

Initial management

As malignant pleural effusions are common in advanced malignancy, if the individual with an MPE has advanced malignancy and is asymptomatic, then intervention may not be required. All pleural interventions carry some measure of risk, and must be weighed against the advantages of intervention.

A retrospective study of over 500 patients with lung cancer found that 40 per cent had a pleural effusion present at diagnosis. Of those, 20 per cent had small, asymptomatic effusions, which did not become symptomatic or require intervention during follow-up. The primary aim of management of MPE is improving symptom control and quality-of-life, hence symptom burden should be assessed initially.

As such, the American Thoracic Society (ATS) guidelines do not recommend intervention for known or suspected MPE, which are asymptomatic.

Of those individuals who have a symptomatic pleural effusion, initial ultrasound-guided thoracentesis should be performed to confirm the presence of malignant cells and a symptomatic response to aspiration. Ideally, large volume, therapeutic thoracentesis should be performed if possible, or drainage via chest tube.

Generally, thoracentesis or chest drain insertion is a safe and straightforward procedure, however, complications are possible; a dry tap, infection, bleeding and tube blockage or dislocation. If the individual has no improvement in symptoms (in particular dyspnoea) another aetiology for their symptoms should be investigated.

Thoracentesis allows for assessment for lung re-expansion and the presence of trapped or unexpandable lung. Trapped lung occurs when the lung fails to re-expand following drainage of pleural fluid and the pleural surfaces cannot oppose.

This may be due to pleural restriction caused by pleural thickening from direct metastatic invasion, a fibrotic process or metastatic deposits. Additionally, the lung may be unable to expand due to endobronchial obstruction from tumours or chronic atelectasis.

Trapped lung is present in approximately 30 per cent of MPE. The lack of pleural opposition means pleurodesis is usually unsuccessful and is also associated with a poorer prognosis. For these individuals, if symptomatic, a discussion regarding the risks and benefits of an indwelling pleural catheter (IPC) should take place.

MPE are generally associated with significant symptoms, most notably dyspnoea. In this population, most will experience a re-accumulation of fluid following initial aspiration, and so definitive pleural intervention is recommended by both the European Respiratory Society and American Thoracic Society.

Recent advances in interventional pulmonology have led to a range of effective treatments for MPE and the underlying choice of intervention is based on the individual’s performance status and the patient’s personal preference.

For patients who developed an MPE in the context of a cancer which is amenable to oncological intervention (chemotherapy, immunotherapy or targeted treatment), due consideration may be given to commencing treatment and monitoring the effusion. Small studies have shown treatment benefits to MPE in non-small cell lung cancer treated with immunotherapy and lymphoma treated with systemic chemotherapy.

Pleurodesis

Pleurodesis is a process whereby a drug or substance is inserted into the pleural space, causing an inflammatory reaction and formation of adhesions between the parietal and visceral pleural. This eliminates the potential space and if successful, prevents pleural fluid re-accumulation. Traditionally there have been many agents available for chemical pleurodesis, however talc pleurodesis remains the most widely used and recommended internationally.

Talc can be delivered either as ‘talc slurry’ where talc is mixed with normal saline and injected via a chest drain at the bedside. Alternatively ‘talc poudrage’ via medical thoracoscopy or video assisted thoracoscopy (VATs) where dry talc is distributed throughout the pleural space.

Talc poudrage has slightly higher success rates, although it does involve a surgical intervention and carries a higher complication rate. Both processes have overall high success rates, ranging from 77-to-98 per cent reported in the literature. The most feared complication is post-pleurodesis acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

The use of medical grade talc has significantly reduced the rates of ARDs post-pleurodesis, with no incidents reported in recent studies. Slurry pleurodesis itself can be a very painful procedure for some individuals and traditionally anti-inflammatory agents are avoided, due to the concern of affecting the success of pleurodesis.

A randomised controlled trial examined the effect of high-dose non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents post-pleurodesis and showed no significant decrease in success rates. In the past it was felt that adequate distribution of talc slurry throughout the pleural space was required for adequate pleurodesis and as such, patients were requested to rotate positions in the hours following pleurodesis.

A recent randomised controlled trial compared patient rotation to supine bed rest, with no significant difference in pleurodesis success rates and hence rotating positions is no longer recommended. Medical pleurodesis, via chest tube, is a good option for patients who are frailer or may not tolerate surgery well, although can require a more prolonged admission, as the effusion must be fully drained prior to pleurodesis.

Surgical pleurodesis, or talc poudrage via video-assisted thoracoscopy under general anaesthetic, or medical thoracoscopy under conscious sedation, offers some advantages over slurry pleurodesis. The invasive nature allows direct visualisation of the pleura, biopsy if necessary, breakdown of adhesions during VATs and direct visualisation of lung expansion. If the lung fails to expand, an IPC can also be placed at the time of intervention.

This naturally also carries procedure-related complications, such as pain at the port sites, infection, bleeding and possible reaction to anaesthetic. As fluid is drained intra-operatively, the patient can generally be discharged home more rapidly. Surgical pleurodesis is an excellent option for fit and independent individuals with a good performance status.

Alternative pleurodesis agents, including bleomycin or doxycycline, have lower reported success rates and are now rarely used. Surgical pleurodesis, via abrasion pleurodesis or pleurectomy, is an option, but again less common.

Indwelling pleural catheters

Up to 30 per cent of patients with MPE will have a non-expandable lung. Lack of opposition of the visceral and parietal pleura mean that pleurodesis is unlikely to be successful. In these cases re-accumulation of pleural fluid can be managed with an IPC.

Flattening of the diaphragm by pleural fluid, preventing efficient contraction of the diaphragm, is considered to be a significant contributor to the dyspnoea associated with pleural fluid and likely contributes to relief gained from repeated aspirations via an IPC, even in the presence of a trapped lung.

An IPC is a tunnelled small bore chest drain. It ends in a one-way valve, allowing the individual or their careers to drain pleural fluid on an as needed basis. IPCs can be inserted at the bedside, with minimal or no sedation required, as a day case. Compared to a traditional chest drain and pleurodesis or surgical pleurodesis, IPCs are less invasive and involve less time in hospital.

IPCs can be a good option for patients with lower performance status who may not tolerate surgical pleurodesis, who wish to avoid surgical intervention or the priority is for rapid discharge.

Complications are rare, but do include procedure-related discomfort, infection, tube blockage and tract metastasis. Notably, significant infection requiring tube removal is rare. Randomised controlled trials comparing pleurodesis and IPCs head-to-head show a significant reduction in hospital days and less repeated interventions for the IPC groups and both groups had a significant reduction in dyspnoea and improvement in quality-of-life, with no significant difference observed.

Currently, the American Thoracic Society and European Thoracic Society recommend IPC placement for patients with evidence of trapped lung or previously failed pleurodesis.

Surgical pleurodesis is an excellent option for fit and independent individuals with a good performance status

There is a growing trend towards a combination approach to the management of MPE. Case series have examined combining IPC placement at the time of surgical pleurodesis. The combination is associated with shorter inpatient length of stay and higher successful pleurodesis rate at seven days. Additionally, studies have examined IPC insertion combined with talc slurry via the IPC tube, with good results.

Summary

In summary, there is a wide variety of management options available for MPE. The main aim of care should be to minimise symptoms and prolong quality-of-life and the decision of modality should be made in conjunction with the patient and considering services available locally. For individuals with good performance status and keen for definitive intervention, medical or surgical pleurodesis is a good option.

For more frail patients or those keen for early discharge, IPCs are well tolerated with excellent success rates. Given that the management of MPE is essentially palliative in nature, the main goal of care is to minimise symptom burden and maximise quality-of-life while minimising side effects from intervention.

References available on request

Case report 1

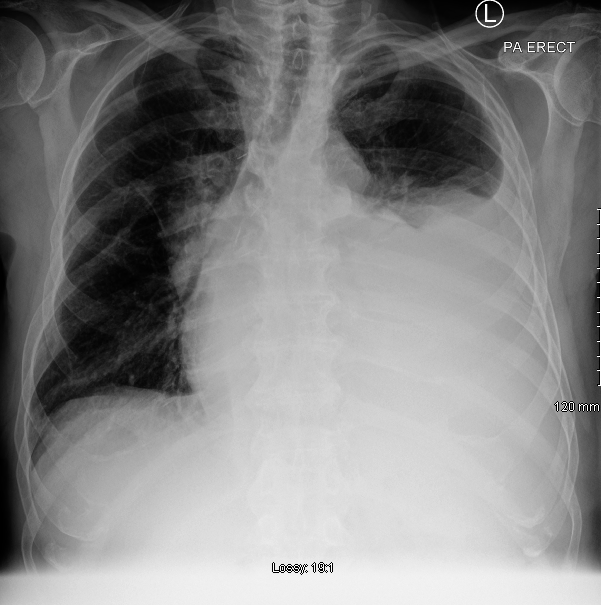

A 67-year-old man presented with dyspnoea, and a chest x-ray performed on admission revealed a large left-sided pleural effusion. (Figure 1) He had a history of oesophageal cancer, surgically resected one year previously and was fit and independent at baseline.

A therapeutic thoracocentesis was performed, 1500ml of pleural fluid was drained and a sample sent for cytology. He had good symptomatic relief and was discharged home. Post procedure chest x-ray confirmed lung re-expansion. Subsequent analysis of the pleural fluid revealed malignant cells consistent with metastatic oesophageal adenocarcinoma.

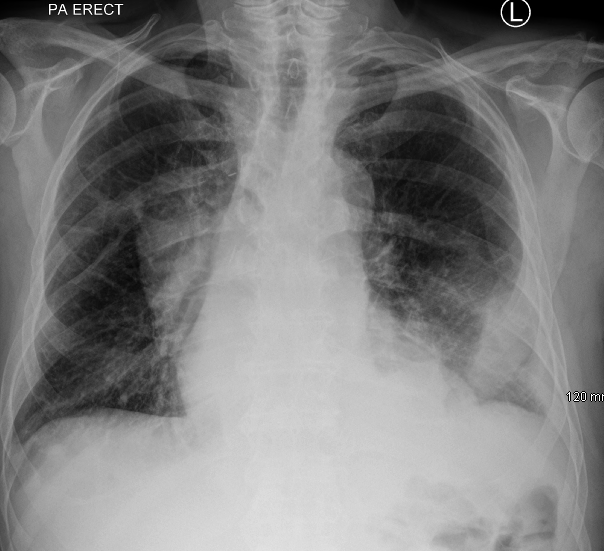

Given his excellent performance status, he was referred to cardiothoracic surgery and a successful talc pleurodesis via VATS was performed. He was discharged home and referred for further oncological management. Post procedure chest x-ray (Figure 2) shows excellent lung expansion.

Case Report 2

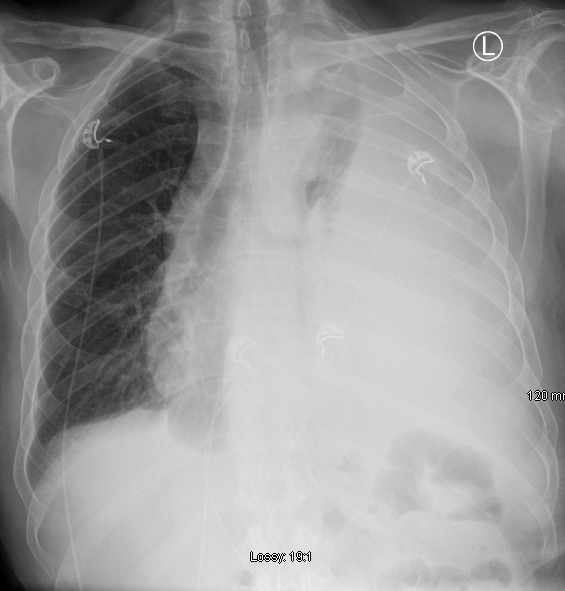

An 82-year-old man was admitted with dyspnoea and a new, large pleural effusion on chest x-ray (Figure 3), on a background of metastatic bladder cancer. He was also known to the medicine for the elderly service for dementia, with a marked recent deterioration in his functional status. He lived at home and had excellent family support.

Given his poor performance status, it was felt he would not be a surgical candidate and prolonged admission for drainage and pleurodesis via chest drain would likely be distressing. After discussion with family, an indwelling pleural catheter (IPC) was placed without complications, with good symptomatic relief on drainage.

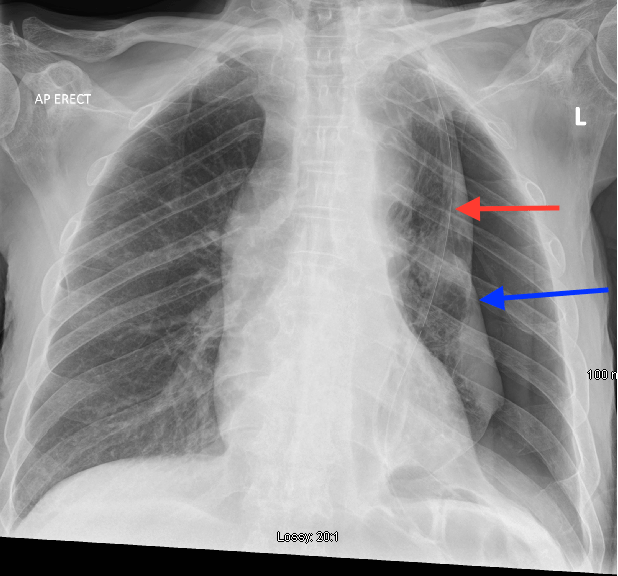

His grandson was educated in management and use of the IPC and he was discharged home well. Post drainage chest x-ray showed a trapped lung (Figure 4, blue arrow: Lung edge) and the IPC, visible on the chest x-ray (Figure 4, red arrow).

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.