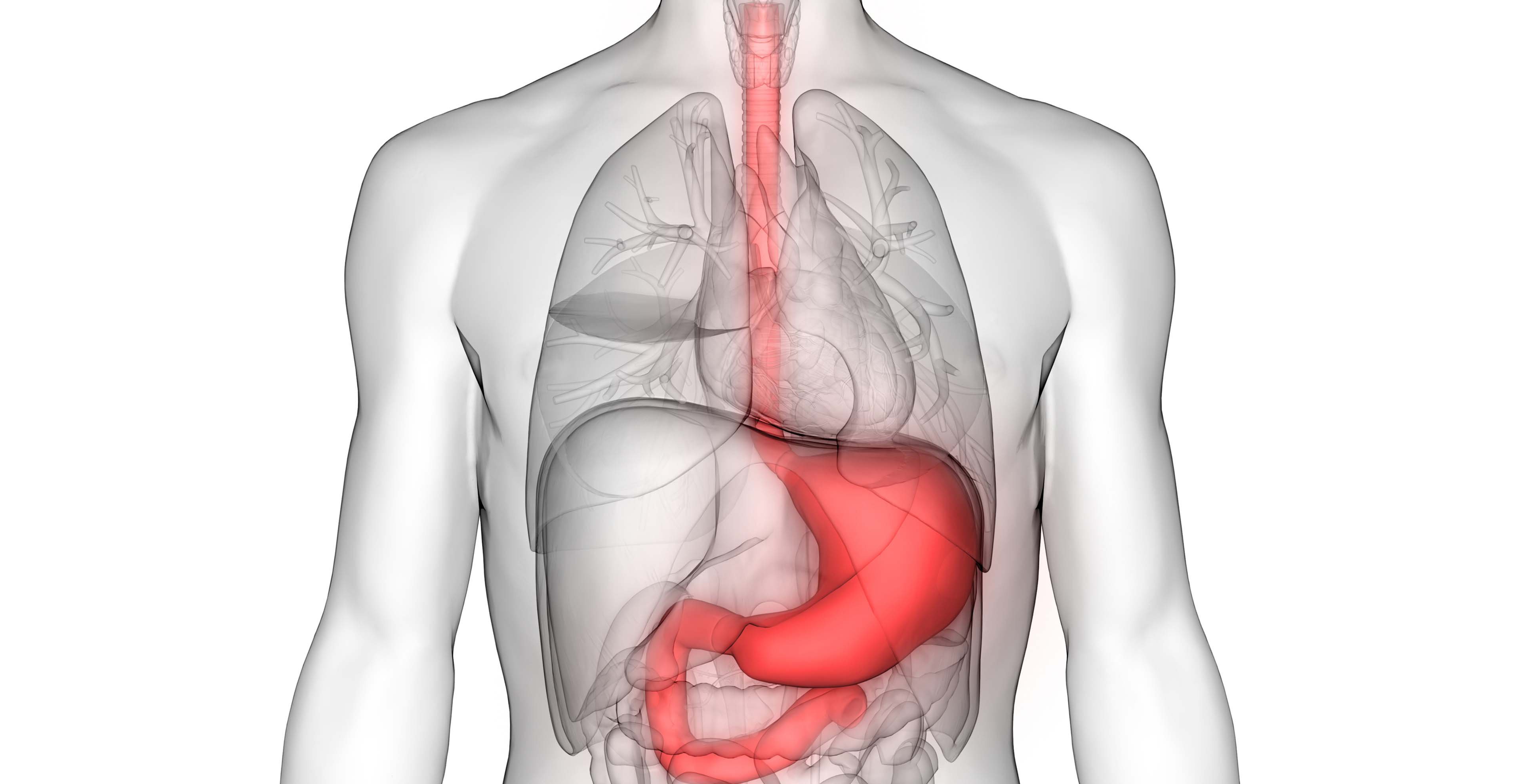

An overview of the latest diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to gastroesophageal reflux disease

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GORD) is a common condition affecting up to 20 per cent of the population. The main symptom is a burning sensation in the mid sternum region commonly described as heartburn. Other symptoms are chest pain, which can mimic a myocardial infarction and water brash, a filling of the mouth with fluid. Extra oesophageal symptoms are nocturnal cough, asthma, laryngitis, recurrent pneumonia and loss of teeth enamel. Because of its variable presentations, GORD remains the leading outpatient physician diagnosis for gastrointestinal disorders in the US, with a very high economic burden on society.

A definition of GORD is troublesome symptoms that may be considered to be moderate or severe on one or more days a week.

Complications include Barrett’s oesophagus, which can affect up to 5 per cent of patients with GORD, and 1 per cent of people with Barrett’s will get oesophageal adenocarcinoma (OAC). OAC is the fastest-rising cancer in the Western world and has risen dramatically over the last 20 years. Oesophageal cancer typically affects people aged between 60 and 80 years, with the most important risk factors being severe long-standing GORD, smoking and heavy alcohol consumption. There were 34,384 new cases of oesophageal cancer recorded in the EU in 2012, with an incidence rate of seven per 100,000 population. The highest incidences recorded are in Ireland, UK and then Netherlands.

Aetiology

GORD is caused by a failure of the oesophageal sphincter. The angle at which the oesophagus enters the stomach creates a valve that prevents the normal acid content of the stomach getting access to the oesophagus. The columnar epithelium lining of the oesophagus cannot withstand acid and leads to inflammation. The presence of a hiatus hernia increases the possibility of reflux. The oesophageal sphincter does not have the benefit of the diaphragm to help its function if the patient has a hiatus hernia. Oesophageal mucosa sensitivity to acid varies and individual mucosa may be more susceptible to acid.

Endoscopy

Upper endoscopy is not required in the presence of typical GORD symptoms. Endoscopy is recommended in the presence of alarm symptoms and for patients who are at higher risk and it reasonable to perform endoscopy to exclude another diagnosis such as Barrett’s oesophagus, which is more common in older male patients over the age of 50 years who are at risk of developing adenocarcinoma.

Routine distal oesophageal biopsies are not recommended in GORD. However, if eosinophilic oesophagitis is suspected from the endoscopic appearance, biopsies in this case should be taken from the lower and mid oesophagus. Gastric biopsies at endoscopy should be taken from corpus, incisura and antrum to evaluate H.pylori, atrophy, intestinal metaplasia or dysplasia.

A urea breath test is recommended as a non-invasive test for active H.pylori infection but does not confirm or establish the diagnosis of GORD. Urea breath test is the examination of choice for patients under the age of 50 years presenting with dyspepsia.

GORD can be classified relative to the presence or absence of erosions on endoscopic examination, which can be classified as non-erosive (NERD), whereas GORD symptoms with erosions constitute erosive oesophagitis.

Management

Lifestyle modification that improves symptoms includes weight loss, a three-hour gap before having a meal and lying down, elevating the head of the bed about six inches, and sleeping in the left lateral position.

Patients should be advised to avoid excess caffeine, chocolate, alcohol, peppermint, acid juices and carbonated beverages and to stop smoking and avoid wearing very tight clothes and bending down after a meal.

A proton pump inhibitor (PPI) trial of empiric short-term of one week is not sensitive or specific enough. A formal course of eight weeks’ duration is required in order to assess treatment response to GORD. Patients’ non-response may have an alternative diagnosis such as peptic ulcer disease, upper gastrointestinal malignancy, functional dyspepsia, eosinophilic oesophagitis or achalasia.

In patients that are refractory to PPIs, a 24-hour oesophageal pH probe and manometry with the patient on a PPI for one week may be considered in order to confirm the diagnosis. Current American College of Gastroenterology guidelines recommend that patients with low test probability of GORD be tested off-medication with a 24-hour pH probe and manometry and those with high pre-test probability of GORD are tested on therapy. Twenty-four-hour pH probe is also recommended before surgery to see if the patient is a suitable candidate.

PPIs are still the mainstay of treatment for GORD. There is a wide range of PPIs available, including omeprazole, pantoprazole, lansoprazole, rabeprazole and esomeprazole. Rabeprazole and esomeprazole are considered to be second-generation PPIs, as they are metabolised differently and have better acid suppression. There is, however, little to choose from in terms of efficacy between the different PPIs.

Inappropriate timing of PPI is the commonest cause of PPI failure. The patient should take their PPI first thing in the morning before food. Ranitidine should be taken nightly but intermittently and subject to tachyphylaxis if the body becomes resistant to the drug within two weeks of their regular intake.

However, if a morning dose is not sufficient to control symptoms, a second dose in the evening may be successful. Failing this, the addition of a H2 receptor antagonist might be helpful but not continuously, as mentioned above. The safety of long-term PPI use has been the subject of debate, because chronic use has been linked to several complications, such as vitamin and mineral malabsorption, pernicious anaemia, gastrointestinal infections, gastric cancer and dementia.

However, the results are from heterogeneous studies and are not consistent and larger studies mostly show no association between PPIs and other conditions. The associations described are at a weak odds ratio of <2, so PPIs long-term are considered safe. However, it is worth trying to stop PPIs if possible after eight-to-12 weeks’ full dose, and then asking the patient to take another month of half dosage, and then switching to a H2 receptor antagonist or an alginate. The patient should be warned of the possibility of rebound hyperacidity on stopping the medication.

Challenges

A major challenge is management of Barrett’s oesophagus. A recent large trial over an eight-year period showed that a combination of esomeprazole 40mgs and aspirin 300mgs was effective in reducing the progression of Barrett’s to dysplasia and cancer.

Surgery in the form of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication has a role, if patients are carefully selected. Patients who benefit from surgery are those who respond to PPIs.

Oesophageal manometry is recommended for pre-operative evaluation before anti-reflux surgery or for patients with persisting symptoms, despite adequate treatment.

Surveillance endoscopy to check progression to cancer for patients who have a diagnosis of Barrett’s oesophagus (confirmed by endoscopy and the presence of intestinal metaplasia on histology) is recommended and should be performed every three years.

Other factors favouring progression include the length of the Barrett’s oesophagus segment, male gender and an older age.

Conclusion

It is important to emphasise that reflux is not normal. Simple lifestyle modifications can go a long way in improving quality of life. It is important not to blame the symptoms on getting older, or to stress and worry. There are alarm symptoms, such as vomiting, unintentional weight loss, difficulty in swallowing, anaemia or recent onset of indigestion, which need to be investigated. Investigation is preferably an endoscopy. GORD, if left untreated, can cause considerable discomfort and leads to a poor quality-of-life.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.