A look at the underlying causes of back pain and the various management approaches

Back pain is rarely from one single source. ‘Discogenic’ back pain may account for up to 45 per cent of cases. The sacroiliac joint or the facet joints are considered to be the cause in 13 per cent, 15 per cent and 40 per cent of cases, respectively.

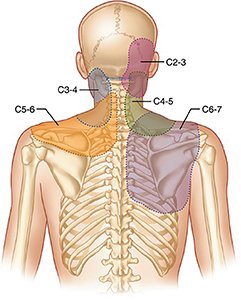

Cervical or neck pain is common and varies in prevalence between 30-to-50 per cent per year. It occurs more often in women with most cases in middle-age. Cervicogenic headache can occur with degenerative change and irritation of the upper cervical facets. Research by Lord, Bogduk and Marsland demonstrated a role for the cervical facets to contribute to neck, shoulder and occasionally interscapular pain.

Thoracic pain symptoms are rare, comprising up to 5 per cent of referrals to outpatient clinics. The rarity makes them significant. We must outrule sinister underlying pathology, including malignancy of the lung, pleura and spine and imaging is recommended if an obvious cause is not apparent. Others include post-surgical pain, herpes zoster, angina, aneurysm, thoracic disc pain and facet pain. From the history, other causes, such as osteoporosis and vertebral collapse, may be more apparent. Rarely, oesophageal malignancy and pancreatic malignancy may present with this type of symptomatology.

Lumbar facet-mediated pain is one of the most common causes of low-back pain. The prevalence ranges from 5-to-15 per cent of the population with axial low-back pain. The process that leads to clinical presentation is usually slow, progressive degeneration that is more prevalent with age.

Sacroiliac joint pain (SIJ) has a prevalence of between 16-to-30 per cent, depending on diagnostic criteria used. It is a cause of axial back pain. It is defined as pain in the region of the SIJ, reproducible by stress and provocation of the SIJ (IASP). The pain is falls in to two categories:

Intra-articular — osteoarthritis (OA), infection, malignancy; and extra-articular — fractures, ligamentous, or myofascial injury.

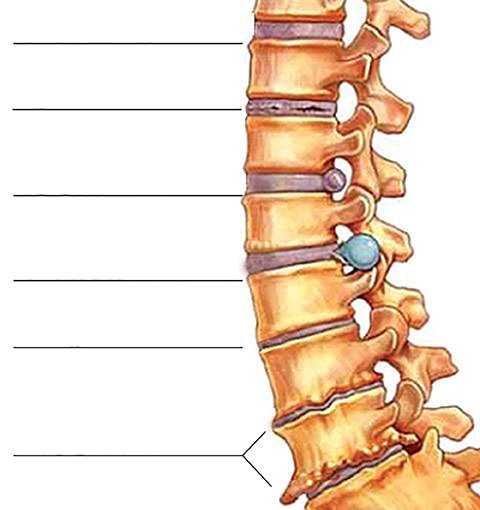

Anatomy

The spine consists of three curves; cervical, lumbar lordosis, and thoracic kyphosis.

The vertebral bodies and discs act as the main ‘shock absorbers’ and stabilisers of the spine. These are supplemented with a combination of ligaments and muscles at different levels. The thoracic spine also gains some stability from the addition of the 12 ribs and their associated muscles.

Ligaments

The three major ligaments which hold the spine together act to stabilise it and protect the disc. These are the ligamentum flavum (through which epidurals just pass to enter the epidural space), the anterior longitudinal, and posterior longitudinal ligaments. Running between the tips of the spinous processes are the supraspinous and interspinous ligaments. There are smaller ligaments between levels and also in the region of the sacroiliac joint that contribute to stability and allow movement in flexion, extension and rotation.

Vertebral bodies

Vertebral bodies are oval, with cancellous bone and posteriorly the vertebral arch, which consist of two pedicles, two lamina, and seven processes. The laminae allow attachment of the ligamentum flavum. The canal between each pair of pedicles form the foramina for nerve roots.

Intervertebral discs

These are composed of an annulus fibrosis made up of fibrous tissue and an inner nucleus pulposus made up of collagen. Each disc forms a fibre-cartilaginous joint, allowing slight movement of vertebrae. With progressive age and degeneration, this reduces almost completely.

Below 40 years of age, about 25 per cent of people show some signs of degeneration at one or more levels; after age 40, more than 60 per cent of people show degeneration at one or more levels on MRI imaging. These do not necessarily correlate with pain and spine pain generation.

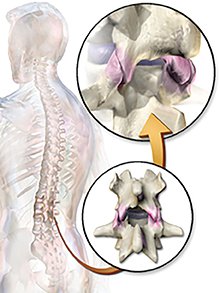

Ageing and degeneration are associated with dehydration of the nucleus pulposus. The annulus fibrosis also weakens with age and there is an increased risk of tearing. The cartilaginous end plate begins to thin out also. This allows fissures to form and with OA degeneration processes, the inner nucleus pulposus can seep out and put pressure on spinal nerves. This is the process resulting in sciatica and other radiating (radiculopathy)-type pain.

Facet (zygapophyseal) joints

These are synovial joints formed between adjacent vertebrae. These act to allow flexion and some extension of the spine, the extent of which depends on the level involved. Their function also involves reduction of anterior shear forces.

Disruption of their function is usually slowly progressive and associated with age and degenerative OA. Facet joints can also become dislocated and fractured but usually, these are part of a trauma presentation.

Facet join arthritis/arthropathy is also associated with age changes and wear and tear. The joints may inflame, which if involving multiple levels, can cause stenosis of the neural foramen or central spinal canal.

Nerve supply is from the medial branch of the dorsal ramus of the exiting nerve at the same level, and also the medial branch of the nerve one level above. This dual innervation is the reason for treating multiple levels when doing diagnostic and therapeutic treatments. These nerves also supply the multifidus muscle and the ligaments and periosteum of the vertebral arches and spines.

Red flags

Non-mechanical causes of spinal pain represent approximately 1 per cent of cases. In these circumstances, 0.7 per cent are due to neoplastic causes. This includes primary spine pathology and secondary metastatic disease.

Diagnoses include multiple myeloma, metastatic carcinoma, lymphoma, leukaemia, spinal cord tumour, retroperitoneal tumours and primary vertebral tumours.

Infectious causes are estimated at about 0.01 per cent. These include osteomyelitis, septic discitis, paraspinous abscess and herpes zoster.

The last group are inflammatory arthritis (0.3 per cent), including ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic spondylitis, Reiter’s syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease. Lesser causes are Scheuermann’s disease and Paget’s disease.

Red flag symptoms include (not exhaustive and patient medical history essential):

• Age <20 or >45 with no precipitating event;

• Night pain;

• Pain with constitutional/systemic symptoms;

• Back pain in the presence of unexplained weight loss;

• Back pain with bladder/bowel dysfunction or leg weakness;

• Insidious onset/progression;

• Back pain not eased by bed rest;

• Back pain that does not vary with activity; and

• Severe acute-onset back pain without trauma.

Investigations

Nothing comes before a thorough history and physical examination.

History

This should start with the usual pain questions but also any variation with movement, sleep, rest, time of day, trauma and falls and also age-specific questions.

Anything that pre-exists in the patient’s medical history should be noted.

Medication in terms of long-term steroid use and any form of anticoagulation use.

Bowel or bladder dysfunction or changes in perineal sensation should trigger urgent referral for spine assessment and MRI.

Any associated subjective limb neurology should be noted.

Examination

Observing gait and completing a full range of motion examination allows us to gain some information before a targeted assessment.

Neurological assessment of limbs should be done, particularly if any radiculopathy is noted. Tendon reflexes, power assessment and sensory testing are useful.

Straight leg raise and FABER test for SIJ, especially lumbosacral spine pain. Flexion and extension of the lumbosacral spine will give some information on involvement of facet joints. Relief with flexion but worsening pain with extension in the presence of tenderness in the paraspinal regions is supportive of facet joint involvement.

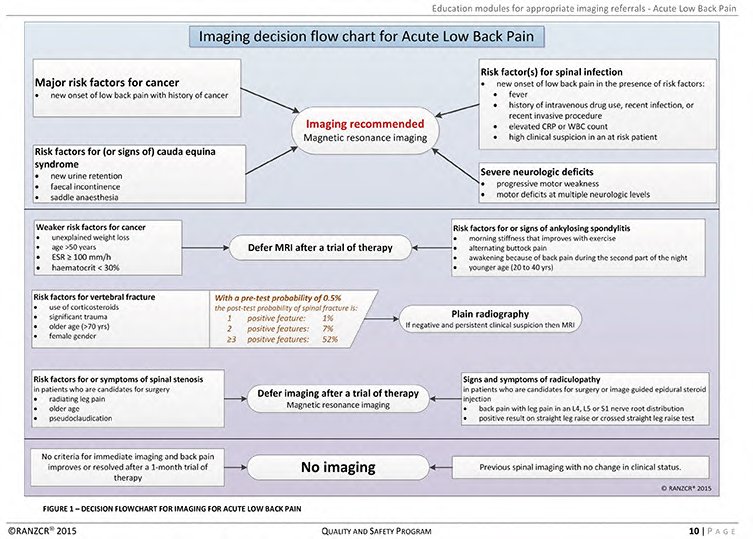

Imaging

In non-specific low-back pain, immediate imaging is not recommended. Usually, unless there are ‘red flags’ or trauma, trials of therapy (medication and physiotherapy) are recommended.

Management

Management of low-back pain has usually started before the patient presents. Use of simple analgesics in the home, heat and ‘rubs’ are often tried before attending.

Following on from initial history, examination and in conjunction with any old or current imaging, treatment plans are made.

Often, it is useful to initiate the idea of lifestyle changes, ie, smoking cessation, weight loss or increased activity levels, early in any plan. This hopefully will make the patient realise that in the case of mechanical back pain, they have an active role.

Pain management will be targeted at symptoms, obviously. The use of medication, physiotherapy and possible interventional pain procedures should be discussed with the patient.

Physiotherapy

Early assessment is extremely helpful. Recommendations for rehabilitative exercises to be continued at home, as well as use of hydrotherapy, heat and massage all have their use in management. Once the acute pain phase is settling, discussions on rehabilitation, activity, exercise and adjuncts such as pilates and yoga can be introduced.

Medication

As above, usually home-based simple oral and topical therapies may have been commenced.

It is essential to be aware of the patient’s current medications and possible interactions that may arise. Also, long-term use of opioids and anti-inflammatory medications can be associated with side-effects which are likely to reduce the patient’s quality-of-life.

Neuropathic pain medication, including gabapentinoids, have significant issues with cognitive impairment, as well as their other side-effects. Patients need to be counselled about these and the fact that there is also a lag phase until they may have a beneficial effect on the pain. Slow titration to effect is essential to avoid early treatment-limiting side-effects.

Tricyclic antidepressants, amitriptyline, nortriptyline and desipramine, are indicated in some patients. They are better if commenced at a low dose and at night-time. Patients should be made aware of anticholinergic side-effects, including dry mouth, blurred vision and urinary retention. This group of drugs may be particularly useful in patients with poor sleep patterns.

All patients should be warned about driving and alcohol interaction with pain medication.

Pain management interventions

Referral to pain management comes when there has been no sustained, significant response to ‘conservative’ management. Occasionally, it arises because of issues with poor medication tolerance, interaction with other medications and patient request.

Initial history and examination are usually repeated and any radiology or physical exams as well as medications trialled are assessed.

Once a plan is agreed with the patient, it is important to explain the idea, for example, in possible facet-mediated back pain, that the process involves more than one stage. They should have a full explanation of the idea of ‘diagnostic’ medial branch nerve blocks, which may only last long enough to confirm the site of the pain generator, and a follow-up radio-frequency thermal rhizotomy. The procedure explanation includes risks, benefits and most common side-effects. Given the potential for multiple pain generators, the idea of multi-level or bilateral treatments should be discussed. The need for ongoing, intermittent, repeated therapy is important to discuss, along with the possibility of sensations such as numbness in the treated area.

Many patients enquire about surgical treatment. This is a reasonable request and it is useful to include it in discussion, along with the prognosis for possible procedures. I will frequently refer the patient if they have a poor response initially or if the response is not sustained for a reasonable period of time.

Surgical management

Surgical management is something that may be considered. Most spine surgeons do diagnostic facet blocks. They also give patients a realistic indicator in terms of outcome before considering surgery.

References on request

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.