CUP remains an important and challenging part of everyday oncology practice

Cancers of Unknown Primary (CUP) are a widely heterogeneous group of metastatic tumours with no identifiable primary site, despite extensive diagnostic workup. They are also known as UKP (unknown primary) and MUO (malignancy of unknown origin). The median age of diagnosis is 60 years with a slight male preponderance. They are reported to comprise 2-5 per cent of all invasive malignancies but CUP can be diagnosed in error in patients in whom suboptimal investigations are carried out. A true CUP is therefore a diagnosis of exclusion and recent advances in radiology and pathology techniques have led to a decrease in incidence of true CUP. Unfortunately, diagnostic and treatment advances in oncology over the past decade have not translated to meaningful improvements in CUP survival statistics. Overall CUP has a poor prognosis with a median survival of three-to-four months, one-year survival of less than 25 per cent and five-year survival of less than 10 per cent.

CUPs are often categorised into favourable and unfavourable subtypes. The less common ‘favourable’ type comprises 20 per cent of CUPs and exhibit more sensitivity to treatments that translates to a more prolonged patient survival. The majority of CUP are considered unfavourable. These are often characterised by early and aggressive metastatic spread, an unpredictable pattern of behaviour, poor response to chemotherapy and overall poor prognosis. CUPs often have inherent chromosomal instability that contribute to the aggressive disease presentation and chemo-resistance. The two clinical factors which have been noted to be prognostic are LDH levels at diagnosis, and patient performance status. The European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) guidelines (2015) state that patients with a good performance status and normal LDH level at diagnosis have a median life expectancy of one year.

This contrasts with patients who either have a poor performance status or an abnormal LDH: These patients have a median life expectancy of four months. There are different hypotheses on the pathogenesis of CUP. One theory includes pro-metastatic cancer development to explain the rapid spread of these tumours with a small and innocuous primary. Additional hypotheses include a malignant stem-cell origin leading to metastases without any primary tumour, or regression of the primary tumour leaving only the metastatic deposits evident.

Indeed, it remains questionable whether polychemotherapy is superior to single agent chemotherapy at all

Diagnostic approaches

As regards diagnostics, a thorough history and physical examination including head and neck, breast, pelvic and rectal examination is essential. This is followed by baseline blood tests, chest x-ray and CT of the thorax, abdomen and pelvis. Specific tumour markers such as prostate specific antigen (PSA), alpha fetoprotein (AFP), beta human chorionic gonadotrophin (bHCG), and chromogranin A (CgA) can help point towards a primary source. Other tumour markers such as Ca125, Ca199 and Ca15-3 are non-specific and often raised irrespective of cancer origin. Further investigations include endoscopy, mammography, breast MRI or testicular ultrasound if the clinical scenario dictates. Whole-body 2-deoxy2-[18F]fluoro-D-glucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET)/CT scans are sometimes performed for CUP, but in the majority of cases they do not significantly aid identification of the primary site. A good quality tissue sample with meticulous immunohistochemistry (IHC) is a key part of the diagnostic process. Initial review of histopathology can differentiate the cancer type into carcinoma, sarcoma, melanoma, and/or lymphoma as well as whether it is well, moderately or poorly differentiated. Further IHC analysis can identify subtypes: adenocarcinoma, germ cell, hepatocellular, renal, thyroid, neuroendocrine, and/or squamous cell carcinoma. Finally, specific IHC stains may point to a potential primary site based on keratin markers such as CK7 and CK20, in addition to others.

The use of extensive IHC staining panels can identify a primary site in about one-third of CUP, however it is much less helpful in poorly or undifferentiated cancers. Substantial efforts have been made to predict the organ tissue of origin of CUPs using DNA sequencing and gene expression profiling (GEP) with the aim to customise treatments and possibly improve clinical outcome. Developed for this purpose, the US FDA-approved Pathwork Tissue of Origin test (Pathwork Diagnostics Inc, CA) uses a 1,550-gene microarray, and the Biotheranostics Cancer Type ID assay uses a 92-gene signature. Other signature gene panels are available ranging from 10 genes to over 1,000 genes in an effort to identify a putative primary site. However, even in the case of positive GEP results and high likelihood of primary cancer source, this has not translated into improved patient outcomes through tailored chemotherapy. A 2019 phase 2 study comparing site-specific treatment based upon GEP results versus standard of care carboplatin and paclitaxel for patients with CUP unfortunately did not demonstrate a significant survival improvement compared with empirical chemotherapy.

Beyond attempting to identify a site of origin, the search for targetable mutations using next generation sequencing (NGS) panels is also being pursued with vigour. CUP commonly reveal amplifications, over-expressions or mutations in oncogenes such as cMYC, Ras, HER2, EGFR and cKIT, and loss or dysfunction of tumour suppressor genes: TP53, PTEN and BRCA among others. A systematic review performed by Lombardo et al evaluated 16 publications of 11 studies that analysed genomic profiling of CUP by various NGS platforms and in differing patient cohorts. Among these studies, 85 per cent of patients demonstrated at least one molecular alteration, including variants of unknown significance. The most frequent being TP53 (42 per cent), KRAS (19 per cent), CDKN2A (9 per cent) and PIK3CA (9 per cent). A mean of 47 per cent of patients harboured a potentially targetable alteration for which approved or off-label drugs were available or where clinical basket trials were recruiting. No two patients sequenced in any of the 11 studies exploring over 3,000 patients had identical molecular profiles, supporting the concept of CUP as individually heterogeneous entities.

Management of CUP

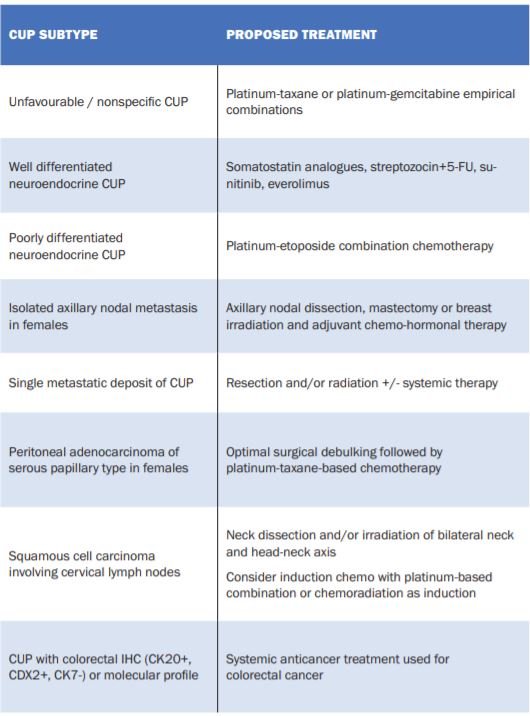

The specific treatment regimen for CUP depends upon the immunohistochemical profile and whether there is any putative tissue of origin considered following multidisciplinary review of clinical, histopathological and radiological findings. There exists specific subtypes that are treated uniquely and have better patient outcomes than standard CUP. These are summarised in Table 1 and modified from the ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for CUP. For instance, colorectal-profile CUP treated with colorectal chemotherapy regimens have a reported median patient survival of 27 months, similar to survival in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer.

In addition, CUP patients noted to have more responsive tumours such as breast-type, colorectal-type, and small cell-type cancers, were found to have significantly improved survival as compared to patients found by GEP to have less responsive tumours, such as pancreatic-type or gastroesophageal-type tumours. CUP without a putative site of origin or unique signature have a poorer prognosis and characteristically are resistant to chemotherapy with tumour response rates in the order of 20 per cent. Platinum combinations can be considered, with taxanes or gemcitabine, but no one regimen has been shown to be superior in efficacy. Furthermore, triplet (three-types of chemotherapy) regimens have not been shown to be superior to doublet chemotherapy. Indeed, it remains questionable whether polychemotherapy is superior to single agent chemotherapy at all. As noted above, using GEP or NGS to establish tissue of origin and adapt the chemotherapy regimen accordingly has not proven successful in improving the survival of patients with standard CUP. The overall goal should be quality-of-life, supportive care and minimising toxicity whilst administering chemotherapy intending to slow or control the disease. There is no second-line chemotherapy option and supportive care should be prioritised.

Recent developments

More recent treatment options include the use of immunotherapy in CUP patients. There has been much interest in this area with early phase, open-label trials of immunotherapy in treatment-naïve and pre-treated patients ongoing. In a phase 2 trial looking at use of pembrolizumab in rare cancers, CUP was one of the groups which showed a promising overall tumour response rate of 23 per cent [NCT02721732]. Biomarkers of response to immunotherapy agents in other tumour types, such as lung cancer, include programmed death-ligand-1 (PD-L1) expression and tumour mutational burden (TMB). The incidence of PD-L1 overexpression (greater than 1 per cent) in CUP has been documented between 20 and 35 per cent. High TMB may also enhance immunotherapy responses and literature reported CUP incidence of high levels of TMB is approximately 12 per cent. A recent development is the approval of pembrolizumab in patients with high microsatellite instability (MSI high) tumours, which was the first FDA tumour agnostic treatment approval. MSI high denotes a group of cancers that are unable to effectively repair DNA errors and therefore develop further mutations, making it more responsive to immunotherapy anticancer strategies. The incidence of MSI high in CUP is low with most studies reporting less than 5 per cent. Using targeted therapies when actionable mutations are found by NGS and other platforms is still under investigation. A systematic review (Lombardo et al) found that up to 85 per cent of patients in these studies show at least one genomic alteration and 47 per cent have a mutation which is targetable.

The most common mutations were TP53, KRAS, CDKN2A and PIK3C. However, there is variation in efficacy of targeted agents across tumour types. BRAF V600E mutations for example, can be successfully targeted in melanoma patients, but show markedly lower responses to treatment in colorectal cancer. In view of this, it is unclear whether an approach to find actionable mutations alone, without determination of the tissue of origin, will yield benefits. On the other hand, certain mutations appear to respond irrespective of primary site, for example, NTRK gene fusions and the recent FDA tumour agnostic approval of NTRK inhibitors. The oncology community in Ireland remains an active part of the global research endeavours with an ongoing trial called CUPISCO [NCT03498521] in University Hospital Waterford and St Vincent’s University Hospital Dublin. CUPISCO is using NGS to determine actionable mutations which can be specifically targeted through use of mutation-directed compounds or immunotherapy. The accompanying review of CUPISCO by Dr Maeve Hennessy and the trials team in Waterford Regional Hospital overviews the particulars of this study.

Summary

CUP remains an important and challenging part of everyday oncology practice. They exhibit poor responses to treatment and have a poor prognosis in the majority of cases. CUPs are widely heterogeneous and unpredictable in behaviour. Efforts to improve diagnosis of the tissue of origin have used IHC panels, GEP and NGS, with modest success to date, but the hard endpoint of better outcomes and survival for patients with CUP has proven challenging. More recent research and trials has focused upon the identification of molecular alterations and mutations within the cancer itself, using novel targeted therapies and immunotherapy. The international clinical trial, CUPISCO, is open in Ireland and enrolling CUP patients. Ongoing scientific work and translational studies are essential to improve our understanding of CUP biology, identify more efficacious treatments and ultimately to improve patient quality-of-life and survival.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.