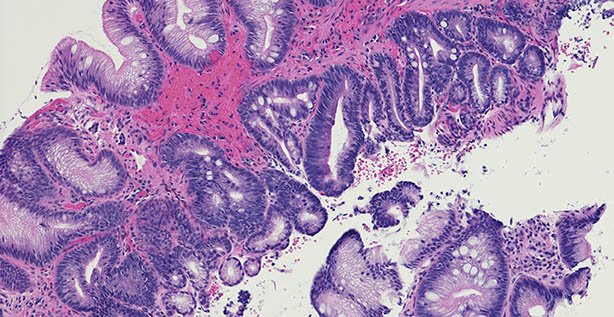

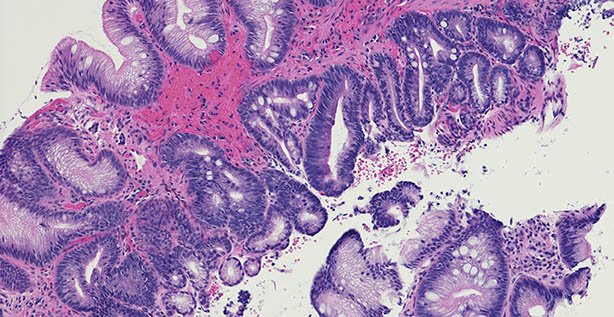

Microscopic photo of a professionally prepared slide demonstrating intestinal metaplasia of the esophagus. Barrett's esophagus caused by gastroesophageal reflux disease. Chronic esophagitis.

High-dose proton pump inhibitors (PPI)

and aspirin chemoprevention therapy, especially in combination, significantly

and safely improved outcomes in patients with Barrett’s oesophagus, according

to the findings of a major trial in the area, the results of which were relayed

to the ISG Winter Meeting by one of the study’s key authors.

Oesophageal adenocarcinoma is the sixth-most common cause

of cancer death worldwide (five-year survival is less than 10 per cent), and is

on the rise, with Barrett’s oesophagus the biggest risk factor.

As

aspirin reduces inflammation and PPIs reduce acid reflux, the Aspirin and

Esomeprazole Chemoprevention in Barrett’s metaplasia Trial (AspECT) aimed to

evaluate the efficacy of high-dose esomeprazole PPI and aspirin for improving

outcomes in patients with Barrett’s oesophagus, explained lead author Prof

Janusz Jankowski, Senior Consultant Physician, University Hospitals Morecambe

Bay, UK.

AspECT is

the first randomised trial to evaluate PPI and aspirin chemoprevention in

Barrett’s oesophagus and the largest randomised trial of Barrett’s oesophagus

ever done, with 20,095 participant-years of follow-up in 2,557 patients. The

trial was carried out at 84 centres in the UK and one in Canada. Patients with

Barrett’s oesophagus of 1cm or more were randomised 1:1:1:1 to receive

high-dose (40mg twice-daily) or low-dose (20mg once-daily) PPI, with or without

aspirin (300mg per day in the UK, 325mg per day in Canada) for at least eight

years, in an unblinded manner.

The

primary composite endpoint was time to all-cause mortality, oesophageal

adenocarcinoma, or high-grade dysplasia.

Between

2005 and 2009, patients were recruited and median follow-up and treatment

duration was 8.9 years.

High-dose

PPI (139 events in 1,270 patients) was superior to low-dose PPI (174 events in

1,265 patients).

Combining

high-dose PPI with aspirin had the strongest effect compared with low-dose PPI

without aspirin (TR 1.59, 1.14–2.23, p=0.0068). The numbers needed to treat

were 34 for PPI and 43 for aspirin. Only 28 (1 per cent) participants reported

study-treatment-related serious adverse events.

Further

work is needed and the AspECT Excel Trial aims to provide longer-term answers.

Speaking

to the Medical

Independent,

Prof Jankowski said the idea of a ‘magic bullet’ is never going to happen, and

it is about balancing benefits and risks in an appropriate way.

“Do I

think you should be on life-long PPIs without anyone ever reviewing you?

Categorically not; that would be insane. What we are saying is that for people

with significant symptoms of reflux disease, not only do they show efficacy,

but we think that long-term PPI use, at least until nine years, is relatively

safe. There may be a low incidence of side-effects but we haven’t seen that,

though it could change with another five-to-10 years of follow-up.

“Secondly,

the combination of low-dose aspirin with PPIs is remarkably safe and there is

evidence of increased efficacy there” [in terms of preventing side-effects from

sudden death and aspiration and bronchopneumonia].

“The third aspect, and the jury is

still out, is whether low-dose aspirin can actually prevent cancer. We didn’t

actually show any cancers being prevented, but we’ve seen the ‘smoking gun’ in

the sense that low-dose aspirin particularly seemed to have an effect on the

premalignant lesions of high-grade dysplasia and we are reasonably confident

that if there had been follow-up for another five or 10 years, we’d be able to

see that breakthrough in preventing oesophageal adenocarcinoma.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.