A round-up of news and oddities from left field by Dr Doug Witherspoon

Unpleasant side-effects are one thing, but there have been periods in history where a seemingly miraculous ‘treatment’ gave the patient more than they bargained for.

Labelling someone a ‘snake oil salesman’, of course, has negative connotations and sometimes for good reason. In Europe in the mid-1800s and the US in the 19th Century, eclectic concoctions containing no snakey substances, but often spices and household herbs were marketed as ‘snake oil liniment’.

However, the use of genuine snake-derived oil had its roots in Asia, particularly from the oil of Chinese water snakes. This oil was rich in Omega-3 and was commonly rubbed onto the tired muscles and joints of Chinese railroad workers after a hard day’s work in the US. This did not escape the attention of Clark Stanley, otherwise known as ‘The Rattlesnake King’.

Ironically, Stanley was a cowboy by profession before studying with a Hopi medicine man whom, he said, enlightened him regarding the healing power of snake oil. He became possibly one of the world’s first travelling pharma reps, touring America to sell his product. This culminated in the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893, when he dramatically produced a rattlesnake from his bag during a presentation, cut the poor beast open on the spot and squeezed it like a dishcloth to produce the venerated oil.

The US FDA stepped in to declare that his products did not contain oil from any type of snake, but by then, the cat – and the snake – was out of the bag and snake oil salesmen popped up everywhere to tout their wares. Thereby a remedy with at least partially-feasible provenance was discredited and the rest, as they say, is history.

‘Medicine shows’ often featured worse elixirs that raised more questions than they answered. The FDA didn’t always cover itself in glory either, and more recently than one might think.

One of the more notable of these remedies was ‘fen-phen’, which the FDA approved in 1996 pending a one-year trial. Fen-phen was originally released as the appetite suppressant fenfluramine and the amphetamine phentermine, and these were respectively pretty useless. However, when they were combined as fen-phen, a four-year trial showed that weight losses of up to 13kg were achieved, with no apparent side-effects. But the researchers failed to monitor cardiac consequences and as you might have guessed, reports began flooding in of heart valve abnormalities. The Mayo Clinic was one of the first to raise the alarm, reporting 24 such cases. Hundreds of similar cases were reported and in the heel of the reel, manufacturers American Home Products Corporation, ended up paying out some $3.75 billion in settlements. The FDA pulled fen-phen in 1997, but more than 50,000 lawsuits followed its withdrawal.

Back to the 1800s in the US, medical researchers were looking for a safe and less addictive alternative to morphine. The answer? Heroin.

Aspirin laced with heroin was marketed at people who had coughs and colds, including children, in 1898. So far so good, until doctors of the time started to notice that patients were coming back for a refill with alarming regularity. Despite the protestations of doctors at the time, heroin was not officially banned as a medical treatment until 1924.

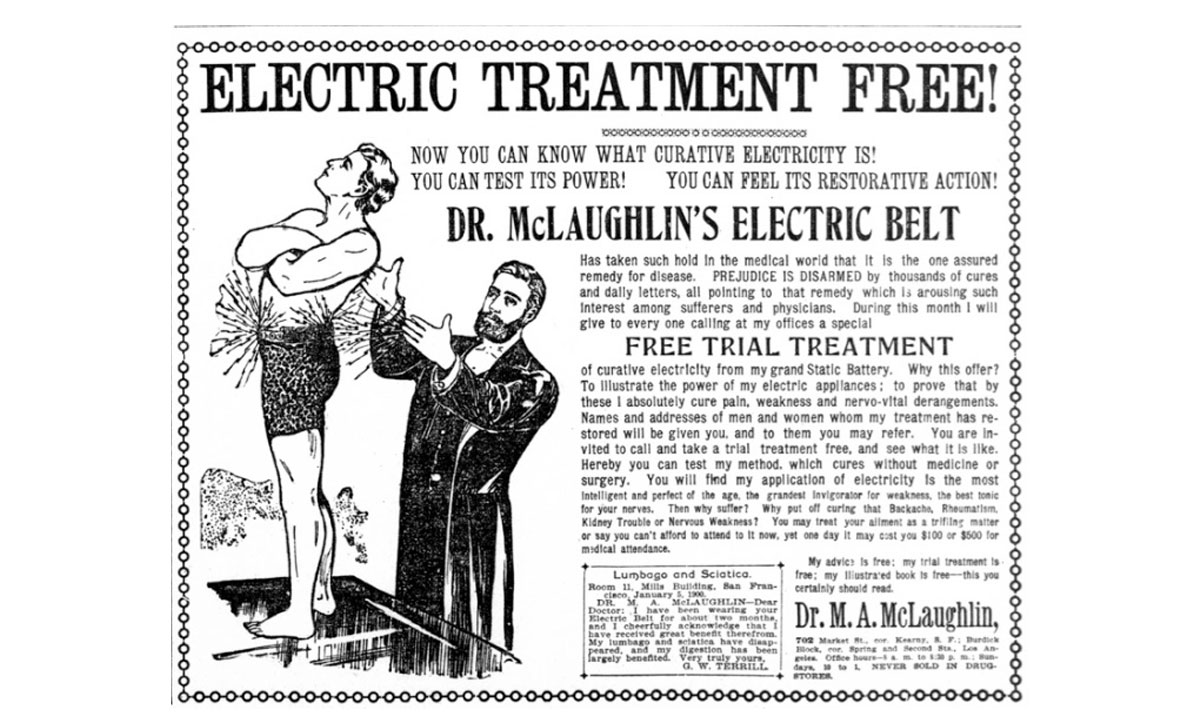

Neither did impotence escape the gaze of those trying to make a buck at the time. Treatments included electric rods inserted into the man’s urethra twice a week, baths filled with electrodes, or ‘electropathic belts’ that were targeted at ‘weak men’ (see image).

In fairness, this is slightly more scientific than the Victorian view of impotence, which was blamed on ‘moral weakness’. By the 19th Century, the waters were muddied even further, with impotence blamed on everything from too much sex to too little sex, masturbation, or “constant excitement of the genital organs without gratification”, wrote Dr Samuel W Gross in his book, Practical Treatise on Impotence, Sterility, and Allied Disorders of the Male Sexual Organs.

As always, your comments and observations on this or any topic are welcome via the email address at the top of the page.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.