For decades healthcare workers have been putting their lives on the line in conflict zones. In the first of a new series

titled ‘On the frontlines’, Bette Browne tells the story of one of them, Dr Lucien Wasingya Kasereka

When he was just three days old, medicine became the life mission of Lucien Wasingya Kasereka. Today he is a surgeon in his native Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) helping to end the agony of obstetric fistula for thousands of women.

“The decision of doing medicine as a career came from my late father, Lusenge Kalwahali Gaudens. He told me the

decision was made when I was three days old,” Dr Wasingya Kasereka told the Medical Independent (MI).

“I had a febrile disease and my life was saved by MSF [Médecins Sans Frontières] doctors. He promised them that his son would be a doctor and save millions of lives. That’s how I was given my mission.” Today, 37 years later, as an obstetric fistula surgeon and founder and Director of the fistula programme in the DRC, Dr Wasingya Kasereka is fulfilling his father’s promise.

In 2012, he completed his medical studies at Univesité Catholique du Graben in the North Kivu city of Butembo, in the eastern part of DRC, where he qualified as a medical doctor. Two years later, he decided to go to Uganda for further studies at Uganda Martyrs University where he qualified as a general surgeon in 2017.

Inspiration

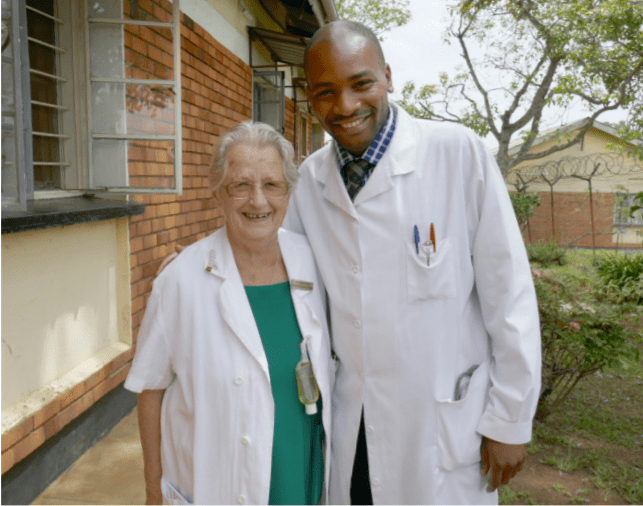

But Dr Wasingya Kasereka is quick to credit others for his success, especially the late pioneering Irish surgeon Sr Dr

Maura Lynch of the Medical Missionaries of Mary, an RCSI Fellow, whom he met while in Uganda where she was

a founding member of the Association of Surgeons in Uganda. That meeting would inspire the next stage in his life’s

mission in medicine.

“Dr Lynch is the pioneer of obstetric fistula surgery in Uganda. She stayed in that country for 30 years and more

than 7,000 women were operated on free of charge by her and her team at Kitovu Missionary Hospital in Masaka

in Uganda.

“She is the one who motivated me to join her team at Kitovu Missionary Hospital. She trained me on how to repair obstetric fistula and inspired me to love these life-changing operations that restore the dignity of suffering women. From there, I decided to help these women with obstetric fistula for the rest of my life.”

In 2020, Dr Wasingya Kasereka decided to return home to the DRC to devote himself to fistula surgery. “I decided to

go back to my home country to continue serving obstetric fistula victims free of charge. I created my own charity, Fistula Programme DRC, and opened the first dedicated obstetric fistula hospital in the region, Butembo Fistula Hospital.

“Ninety patients have been operated on free of charge in DRC under the sponsorship of the Fistula Foundation US, the

International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, and the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA).”

The UNFPA, which is leading a global campaign to end fistula by 2030, describes it as one of the most serious

and tragic childbirth injuries. It occurs when a hole, or fistula, is caused between the birth canal and bladder and/

or rectum due to prolonged, obstructed labour without access to timely, high-quality medical treatment.

Sr Dr Maura Lynch and Dr Lucien Wasingya Kasereka in 2017 at Kitovu Hospital in Masaka

“It leaves women leaking urine, faeces or both and often leads to chronic medical problems, depression, social isolation, and deepening poverty.” Obstetric fistula has been virtually eliminated in industrialised countries through the availability of timely and advanced medical treatment for prolonged and obstructed labour, namely Caesarean section, UNFPA notes. “Today, obstetric fistula occurs mostly among the poorest and most marginalised women and girls, especially those living far from medical services and those for whom services are not accessible, affordable or acceptable.”

It estimates that hundreds of thousands of women and girls in Africa, Asia, Arab states, Latin America, and the Caribbean are living with fistula, with new cases developing every year.

“Yet fistula is almost entirely preventable,” UNFPA emphasises. “Its persistence is a sign of global inequality and

an indication that health and social systems are failing to protect the health and human rights of the poorest and most

vulnerable women and girls.”

Without emergency intervention, obstructed labour can last for days, resulting in death or severe disability. The

obstruction can cut off blood supply to tissues in the woman’s pelvis. When the dead tissue falls away, she is left with a

fistula in the birth canal.

Tragically, there is a strong association between fistula and stillbirth, with research indicating that approximately 90

per cent of women who develop obstetric fistula end up delivering a stillborn baby, according to the UNFPA.

Left untreated, obstetric fistula causes chronic incontinence and can lead to a range of other physical ailments, including frequent infections, kidney disease, painful sores, and infertility.

The physical injuries can also result in social isolation and psychological harm. Women and girls with fistula are often unable to work and many are abandoned by their husbands and families and ostracised by their communities, driving them further into poverty.

Fistula in the DRC

In the DRC alone, according to Dr Wasingya Kasereka, between 5,000 and 10,000 women and girls suffer every year

with fistula with no access to proper care. “Cases of obstetric fistula are on the rise in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Uganda with few fistula surgeons and few facilities which are able to provide fistula care,” Dr Wasingya Kasereka told the MI.

The fistula programme, he explained, “was born in a particular context where Congolese women have lived in conditions of advanced vulnerability for several decades, following a very unstable socio-political situation.” “The context of socio-security crises creates massive displacements of populations, making women the first-line victims. Health crises only worsen an already precarious situation. These include the resurgence of the Ebola epidemic, but also the cholera pandemic in several regions of the country, not to mention the coronavirus that has claimed victims at all levels for more than a year now.

“To all this can be added the health conditions, which are below standards in several regions of the country. This affects women in general, not only in terms of their fundamental rights, but also in terms of their health.”

From there, I decided to help these women

with obstetric fistula for the rest of my life

Fistula Programme DRC is mainly interested in maternal and reproductive health, specifically in women with obstetric fistula problems, Dr Wasingya Kasereka said. Its main objective is to restore the dignity of women. “Some obstetric fistula patients can be easily treated with non-surgical intervention, but the most common treatment is surgery. However, women with obstetric fistula are often from low-income families with no financial support and suffer from severe stigmatization within their communities,” Dr Wasingya Kasereka said on the 2020 United Nations Day to End Obstetric Fistula.

“Many in sub-Saharan Africa consider obstetric fistula to be a divine punishment. Women are therefore stigmatised. They are rejected by their family, divorced by their husbands, and abandoned within their community in the belief they must pay for their ‘sins’.” The DRC, which was formerly Zaire, is located in Central Africa. It is the second-largest country in Africa, after Algeria, with a population of more than 90 million.

The DRC, which was formerly Zaire, is located in Central Africa. It is the second-largest country in Africa, after Algeria, with a population of more than 90 million. Its history has largely been one of exploitation and suffering, especially under Belgian rule. The country achieved independence from Belgium in 1960, but was subsequently consumed by decades of conflict.

Nine African countries and around 20 armed groups became involved in a war from 1998 to 2003, which resulted in the deaths of over five million people. The human rights situation in the country remains dire, according to Human Rights Watch, with more than 5.2 million people internally displaced and nearly a quarter of the population living in severe food insecurity. The poverty rate is well above average, with about 60 per cent of the population living on less than $2 a day.

In a report last year, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Ms Michelle Bachelet said she was appalled by the increase in brutal attacks on innocent civilians by armed groups, and by the reaction of the military and security forces who had also committed grave violations, including killings and sexual violence.

“Violence and political instability continue to plague the Democratic Republic of Congo,” the Fistula Foundation says, “effectively crippling its limited maternal healthcare infrastructure and abandoning women who are suffering with fistula. These grinding conditions prompted author and humanitarian Ms Lisa Shannon to call it the worst place on earth to be a woman.’

Conflict

Dr Wasingya Kasereka grew up in North Kivu, a tumultuous region in the northeast of the country. “The horrors of war and violence have been permanent for over 18 years now, which has significantly affected maternal and child health,” he explained. “Our vision is to restore the fistula victims’ dignity in DRC after a long period of political instability.” Such political instability, in a country in which rape has been widely documented as a widespread weapon of war among armed groups, prompted a visit to the North Kivu capital Goma in 2013 by former Irish President Mary Robinson on a UN peace mission.

Dr Wasingya Kasereka said there is an urgent need to train more doctors and nurses for obstetric fistula care and such

training is a central part of the work of the fistula programme. “Fistula Programme DRC is engaged in the training

of nursing staff and health providers on fistula care and prevention as well as in educating Congolese communities on

obstetric fistulas.”

Fistula is not only a debilitating physical condition; it also presents huge psychological and societal issues for women and girls, Dr Wasingya Kasereka emphasised.

Every year we meet more than 50

women who had been suffering for many

years without any help or hope

“Most of our patients meet our teams after suffering for many years. They leak urine or stool all the time and they are stigmatised by their families or communities. They lose their dignity and hope. Most of them are from poor families and are vulnerable and needy. Every year we meet more than 50 women who had been suffering for many years without any help or hope.

“These women suffering with obstetric fistula isolate themselves, they are stigmatised, rejected and some of them get psychosis and others are depressed, stressed, and traumatised. When we take care of them we consider surgery, psychotherapy and socio economical reintegration. By the time they are discharged they have hope and joy because their dignity has been restored.

“Of course, we face many challenges. Some patients get information about fistula care but they hide in the community and they don’t easily accept the treatment. There is a need to increase awareness in the community. Women who have undergone obstetric fistula care have become ambassadors of the service we provide, helping to raise awareness and increase knowledge of obstetric fistula in the community.”

Dr Lucien Wasingya Kasereka and his team with post fistula repair patients in August 2021 in Kinshasa

To spread the word even further, Dr Wasingya Kasereka and his team carry out fistula camps each year. “Through these camps, we can carry out around 30-to-60 obstetric fistula treatments for free, while allowing a greater number of women to access the service. Through media engagement on radio and TV, as well as through church announcements and ambassadors, we can inform a wide number of people of the fistula camps.”

Dr Wasingya Kasereka told MI that the battle to end obstetric fistula is under serious threat due to the Covid-19

pandemic. “My worst experience was to do obstetric fistula camps during the pandemic in low resource facilities with out enough PPE [personal protective equipment].”

But despite such challenges on the frontlines, Dr Wasingya Kasereka said the rewards for such work are enormous and he would encourage more doctors to consider practising fistula surgery. “The reward we get is that joy and hope that patients experience after healing from obstetric fistula. We feel happy and satisfied when we see the happiness of these patients. I would encourage more doctors to join us and restore women’s dignity.”

FACTS ON FISTULA

Up to three million women and girls,nmainly in 55 developing countries across Asia and Africa, are living with

untreated obstetric fistula.

The UN is campaigning to end this agonising condition by 2030. Since 2013 it has designated 23 May each year as International Day to End Obstetric Fistula, promoting global action towards treatment and prevention.

Obstetric fistula is caused by a very long or obstructed labour when women do not have access to quality obstetric

care services.

It can largely be avoided by delaying the age of first pregnancy, ending harmful traditional practices, and timely access to quality obstetric care, especially Caesarean section.

Most genital fistula can be repaired surgically. But there are numerous challenges facing those providing fistula repair services in developing countries, including a dearth of available surgeons with specialised skills, operating rooms, equipment and funding from local or international donors to support both surgeries and post-operative care.

More women and girls will be at risk of obstetric fistula due to overburdened health systems. During Covid-19, fistula repairs have been widely suspended as they are deemed to be non-urgent and hospitals have diverted resources to

care for patients with Covid-19.

It is expected that 13 million more child marriages could take place by 2030 than would have otherwise, because the economic fallout from the pandemic is more likely to cause families to ‘marry off’ daughters to alleviate the burden of caring for them.

The UN’s target to end fistula by 2030 will not be obtainable, experts say, unless sufficient resources are mobilised so that affected countries can develop their own sustainable eradication plans, including access to safe delivery and emergency obstetric services.

The main treatment remains corrective surgery, but due to a global shortage of fistula surgeons, current treatment rates indicate that only one woman in 50 receives a fistula repair.

(Sources UN, WHO, International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.