While currently there is no cure for endometriosis, in most cases, symptoms improve with the use of medications, surgery, or both.

Note: The author of this article recognises that there are individuals living with endometriosis who are transgender, who do not menstruate, who do not have a uterus or who do not identify with the terms used in literature. For the purposes of this article, the term “women with endometriosis” is used, however, it is not intended to, exclude, isolate or diminish any individual’s experience nor to discriminate against any group.

Endometriosis is a chronic, painful and debilitating gynaecological condition characterised by the presence of endometrial-like tissue in anatomical positions and organs outside of the uterine cavity.¹ Establishment and growth of such endometriotic tissue is oestrogen-dependent.

The main clinical manifestations are chronic pelvic pain and impaired fertility. The exact prevalence of endometriosis is unknown, but estimates range from 2-to-10 per cent within the general female population and up to 50 per cent in infertile women.

It is estimated that at least 190 million women and adolescent girls worldwide are currently affected by the disease during reproductive age, although some women are affected beyond menopause.2,5

The extent of disease varies considerably from isolated peritoneal lesions to widespread pelvic adhesions, infiltrating lesions, and ovarian cysts. Most endometriotic disease is located on the pelvic peritoneum including the ovaries, fallopian tubes, the bowel, and the areas in front, on the back, and to the sides of the uterus, while a smaller percentage involves the ureters, bladder, urethra, and the upper abdomen.

The condition is not limited to the pelvis, and occasionally can cause damage to extra pelvic structures, such as the pleura and the pericardium, however, it rarely extends beyond the peritoneal cavity.1,2

Theories on the origin of endometriotic lesions in the peritoneal cavity exist, however, there is no coherent theory to explain all the different types of endometriosis, integrating the epigenetic, genetic, immunological, and environmental data.

The most recognised pathogenic theory is Sampson’s theory, suggesting that with retrograde menstruation, viable cells and menstrual fragments can migrate through the fallopian tubes, infiltrate into the peritoneal cavity, then proliferate and cause chronic inflammation.2,3

However, the fact that retrograde menstruation is not enough to cause endometriosis in all affected women indicates that other factors also contribute to the development of the disease.

Other theories, such as the coelomic metaplastic theory, the stem cell theory, the Müllerian remnant theory, and the vascular and lymphatic metastasis theory, are necessary to explain some forms of endometriosis.

The pathophysiology of endometriosis is strongly influenced by factors such as genetic predisposition, and hormonal factors such as resistance to progesterone, oestrogen dependence; inflammation, angiogenesis, and vascularisation processes.

Oxidative stress, resistance to apoptosis, and immunological factors are also involved to various degrees in lesion development.3

Several predisposing factors have been linked with the risk of developing endometriosis. Early age at menarche (below 11 years old), shorter duration of menstrual cycles (of less than 27 days), menorrhagia, and nulliparity increase the risk for endometriosis, indicating that it is closely linked with the female hormonal system.

On the contrary, there are protective factors against endometriosis, mainly acting via lowering the inflammatory process, or by decreasing the levels of oestrogen in the body.

Protracted breastfeeding, current oral contraceptive use, tubal ligation, and smoking are related to a decreased risk for endometriosis. Although the mechanism is still not clear, women who smoke have lower levels of oestrogen in the body.2

Presentation

The clinical presentation of endometrial disease differs not only in presentation, but also in duration. Symptoms of endometriosis can begin prior to the first menstrual period and for many it can persist into menopause and throughout their lives.

Endometriosis triggers a chronic inflammatory reaction resulting in pain and adhesions, and can have a profound effect on an individual’s quality-of-life. Adhesions develop when scar tissue attaches separate structures or organs together. Pain and symptoms due to endometriosis may vary during the menstrual cycle as hormone levels fluctuate.

Symptoms may be worse at certain times in the menstrual cycle, with ovulation, and prior to and during menstruation being the most severe for many. While some experience severe pelvic, bladder and/or bowel pain, others may have few or no symptoms or regard the symptoms as simply period pain or cramps.4

Typical symptomatology includes dyspareunia, dysmenorrhoea, dysuria, dyschezia, and/or infertility. The pain is usually characterised as chronic, cyclic, and progressive.2 Some women experience hyperalgesia, which indicates neuropathic pain.

Three subtypes of endometriosis often overlap; superficial peritoneal lesions, ovarian endometrioma, and deep infiltrating endometriosis.

Patients with bowel endometriosis often present with a wide range of gastrointestinal symptoms, such as diarrhoea, constipation, abdominal pain or bloating, and mimic other clinical conditions like inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) or irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

Rectovaginal endometriosis is a severe deep infiltrating form of the disease involving the vagina, rectum, and the rectovaginal septum. It can present with bowel irritation, dyspareunia, dysmenorrhoea, dyschezia, and rectal bleeding coinciding with menstrual bleeding.

Infertility is a main symptom that often leads clinicians to suspect endometriosis even in asymptomatic patients.2

Endometriosis is one of the leading causes of infertility, however, it is estimated that 60-to-70 per cent of women with endometriosis will conceive, and this may increase with the removal of endometriosis and the use of assisted reproductive techniques.4

Diagnosis and classification

Diagnosis of endometriosis is often delayed on average of four-to-11 years from the onset of symptoms. According to the Endometriosis Association of Ireland (EAI), the average delay in Ireland is nine years.2,4

This phenomenon is attributed to the non-existence of a pathognomonic test or biomarker to detect the disease, the diversity of symptoms being considered physiologic responses during menstruation, and to the wide range of reported symptoms that overlap with other gastrointestinal or gynaecological conditions.2

The diagnosis process commences by taking a detailed history and carrying out a gynaecological physical examination.

Positive family history, pelvic pain, benign ovarian cysts, pelvic surgeries, and infertility issues can lead to a suspected diagnosis of endometriosis. Physical examination can reveal variable findings, depending on the location and size of the endometriotic lesion.

Tenderness on vaginal examination, palpable nodules in the posterior fornix, adnexal masses, and immobility of the uterus are indications of endometriosis. The absence of physical findings cannot exclude the diagnosis of endometriosis.2

The European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) Guidelines on Endometriosis were updated in 2022, and offer best practice advice on the care of women with endometriosis, including recommendations on the diagnostic approach and treatments for endometriosis for both the relief of painful symptoms and infertility due to endometriosis.

It provides more than 100 recommendations, is a full revision of, and replaces, the ESHRE Guideline on Endometriosis 2014, with major changes in recommendations regarding the relevance of diagnostic laparoscopy and post-operative hormone therapy. In addition, a new section on endometriosis in adolescence provides information on diagnosis and appropriate treatments for symptom management in female adolescents and young adults.

The topics of menopause, pregnancy, and fertility preservation in relation to endometriosis are addressed in more detail in the updated guidelines,5 which are available at: www.eshre.eu/Guidelines-and-Legal/Guidelines/Endometriosis-guideline.aspx.

The ESHRE 2022 guidelines make the following recommendations: Laparoscopy is no longer the diagnostic gold standard, and is now only recommended in patients with negative imaging results and/or where empirical treatment was unsuccessful or inappropriate.

The ESHRE guideline development group (GDG) recommends that clinicians should consider the diagnosis of endometriosis in individuals presenting with cyclical and non-cyclical signs and symptoms; dysmenorrhoea, deep dyspareunia, dysuria, dyschezia, painful rectal bleeding or haematuria, shoulder tip pain, catamenial pneumothorax, cyclical cough/haemoptysis/chest pain, cyclical scar swelling and pain, fatigue, and infertility.5

The guidelines strongly recommend that clinicians should not use measurement of biomarkers in endometrial tissue, blood, menstrual, or uterine fluids to diagnose endometriosis.6

CA125 is elevated in patients with endometriosis, but should not stand alone as a diagnostic test.

The reason is that CA125 can be increased in several pathological conditions, and is also not able to define the location of endometriotic lesions.2

The guidelines also strongly recommend that clinicians use imaging ultrasound (US) or MRI in the diagnostic work-up for endometriosis, but need to be aware that a negative finding does not exclude endometriosis, particularly superficial peritoneal disease.6

In patients with negative imaging results or where empirical treatment was unsuccessful or inappropriate, the GDG recommends that clinicians consider offering laparoscopy for the diagnosis and treatment of suspected endometriosis. They also recommend that laparoscopic identification of endometriotic lesions is confirmed by histology, although negative histology does not entirely rule out the disease.6

Classification: The American Society of Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) has developed a staging system to stage endometriosis and adhesions due to endometriosis.

- Stage 1 and 2 (minimal-to-mild disease): Superficial peritoneal endometriosis. Possible presence of small deep lesions. No endometrioma. Mild filmy adhesions, if present.4

- Stages 3 and 4 (moderate-to-severe disease): The presence of superficial peritoneal endometriosis, deeply invasive endometriosis with moderate to extensive adhesions between the uterus and bowels and/or endometrioma cysts with moderate to extensive adhesions involving the ovaries and tubes.4

The classification was originally developed to predict impairment to fertility, and is therefore focused on ovarian disease and adhesions. Patients with the same ‘stage’ of disease may have different disease presentations and types, and some forms of severe disease, such as invasive disease of the bowel, bladder, and diaphragm, are not included.4

Apart from the classification system, three subtypes of endometriosis can be distinguished according to localisation: Superficial peritoneal endometriosis, cystic ovarian endometriosis (endometrioma or ‘chocolate cysts’), and deep endometriosis, also referred to as deeply infiltrating endometriosis. The different types of disease may co-occur.4

- Superficial peritoneal endometriosis is the most common type. Lesions involve the peritoneum, are flat, shallow, and do not invade the space underlying the peritoneum.4

- Cystic ovarian endometriosis (ovarian endometrioma) occurs less commonly. The cyst is filled with old blood, and because of the colour are referred to as ‘chocolate cysts’. Most people with endometrioma cysts will also have superficial and/or deep disease present elsewhere in the pelvis.4

- Deep endometriosis is the least common subtype. An en dometriosis lesion is defined as deep if it has invaded at least 5mm beyond the surface of the peritoneum. Deep lesions involve tissue underlying the retroperitoneal space.4

Treatment

There is no cure for endometriosis, and treatment is broadly divided into two main categories; pharmacological and surgical. Currently, there is no specific drug that can inhibit disease progress, other than hormonal and non-hormonal agents used to alleviate symptoms and increase fertility rates.

Treatment of endometriosis depends on the severity of symptoms, reproductive plans, patient’s age, medical history and side-effects of both surgical and medical treatments. Regarding treatment of symptoms in post-menopausal women, the potential increased risk of underlying malignancy in this population should be keep in mind and the uncertainty of the diagnosis, as pain symptoms may present differently in this group compared to pre-menopausal women.6

NSAIDs or other analgesics, either alone or in combination with other treatments, can be used to reduce endometriosis-associated pain.8 ESHRE guidelines recommend offering women hormone treatment; combined hormonal contraceptives, progestogens, GnRH agonists or GnRH antagonists, as one of the options to reduce endometriosis-associated pain. The ESHRE GDG recommends that clinicians take a shared decision-making approach, and take individual preferences, side-effects, individual efficacy, costs, and availability into consideration when choosing hormone treatments for endometriosis-associated pain.5,6

Ovarian suppression can reduce disease activity and pain. Systematic reviews have confirmed the efficacy of combined hormonal contraceptives and continuous progestogens, including medroxyprogesterone acetate, norethisterone, cyproterone acetate, or dienogest, for pain associated with endometriosis. Second-line medical treatments include GnRH agonists and the levonorgestrel releasing intrauterine device (IUD).

Danazol and the anti-progesterone gestrinone should not be used, as androgenic side-effects outweigh benefits. Ovarian suppression with GnRH agonists improves symptoms but induces vasomotor symptoms in most women, and prolonged use of more than six months can lead to bone demineralisation.

Prospective studies have shown that this bone loss is reversible and that concurrent treatment with a low-dose oestrogen and progestogen hormone replacement therapy (HRT) regimen or tibolone can extend use without reducing treatment efficacy.

There is limited evidence from randomised trials to show superior efficacy of one ovulation suppression treatment for pain over another, and, in clinical practice, choice of treatment is commonly guided by the tolerability of available treatments. GnRH agonists are sometimes used to trial how a patient might respond to surgical menopause, but the predictive value of this approach is not known.7

In women with endometriosis-associated pain refractory to other medical or surgical treatment, it is recommended to prescribe aromatase inhibitors, as they reduce endometriosis-associated pain. Aromatase inhibitors may be prescribed in combination with oral contraceptives, progestogens, GnRH agonists or GnRH antagonists.6

Surgical treatment to eliminate endometriotic lesions and divide adhesions has long been an important part of the management of endometriosis. Historically, surgical approaches were achieved at open surgery, but in recent decades, laparoscopy has dominated.

Elimination of endometriosis may be achieved by excision, diathermy, or ablation/vaporisation. Division of adhesions aims to restore pelvic anatomy. Some clinicians use interruption of pelvic nerve pathways with the intention of improving pain control.5

Surgery is recommended as one of the options to reduce endometriosis-associated pain. When surgery is performed, clinicians may consider excision instead of ablation to reduce endometriosis-associated pain. Clinicians can consider hysterectomy with or without removal of the ovaries, with removal of all visible endometriosis lesions, in women who no longer wish to conceive and who have failed to respond to more conservative treatments.

The ESHRE GDG recommends that when hysterectomy is performed, a total hysterectomy is preferred.6 Women should be informed that hysterectomy will not necessarily cure the symptoms or the disease. When a decision is made to remove the ovaries, the long-term consequences of early menopause and possible need for HRT should be considered.5 Oestrogen as HRT is advised for those aged under 45 years and/or symptomatic women after oophorectomy for endometriosis, but HRT or tibolone can potentially lead to recurrence. There is, however, no indication to use combined HRT after hysterectomy for endometriosis.7,8

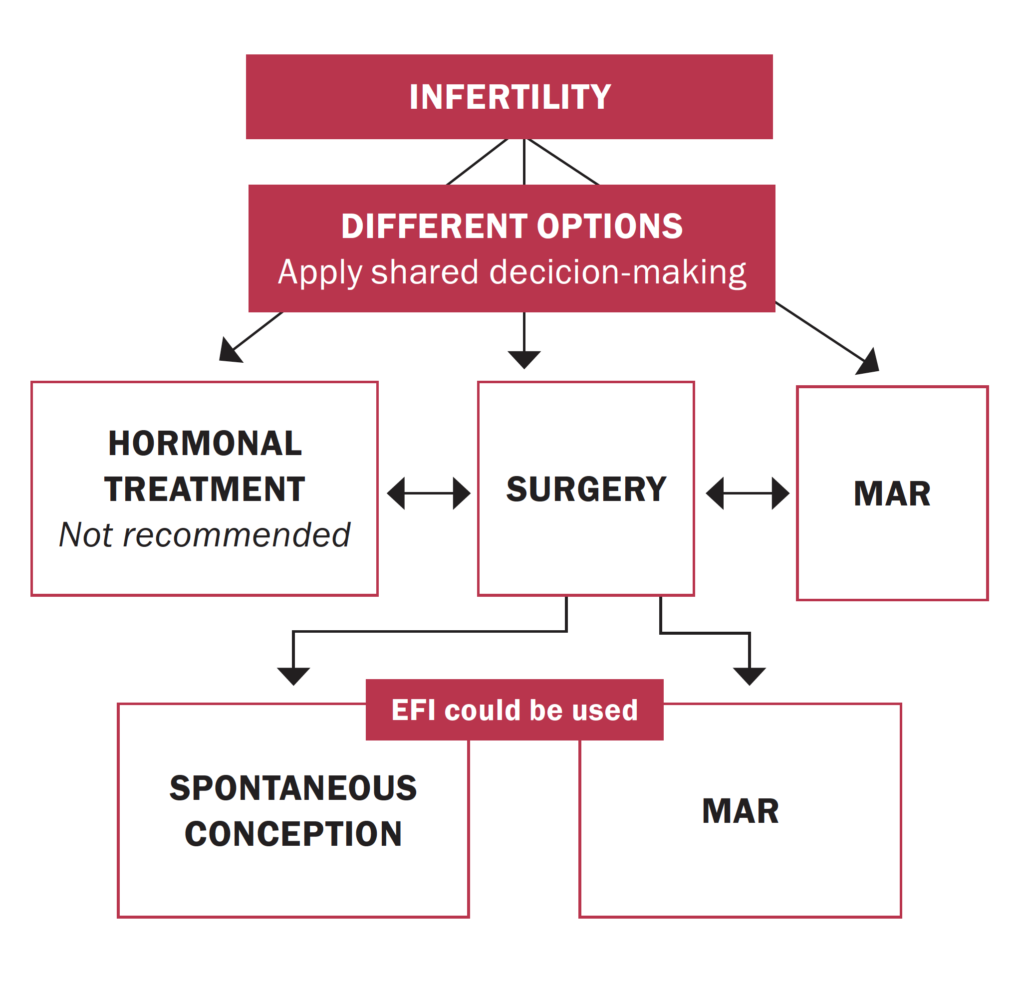

Infertility: An estimated 25-to-50 per cent of women with infertility have endometriosis, and around 30-to-50 per cent of women with endometriosis are infertile. The mechanisms linking endometriosis and infertility are poorly understood, and causation is not established. Even mild endometriosis can impair fertility, and severe disease can lead to tubal adhesions, reduced ovarian reserve and oocyte and embryo quality, and poor implantation. Endometriosis can further impair fertility by disturbing the function of the fallopian tube, embryo transport, and the eutopic endometrium.7 Treatment focuses on improving fertility by removing or reducing endometrial glands and stroma, and restoring normal pelvic anatomy. Treatment decisions for infertile women with endometriosis should consider pelvic anatomy, extent of disease, ovarian reserve and age, male factors, presence of endometriomas, and duration of infertility. Options can include expectant management, surgical removal of ectopic implants, ovulation induction, or IVF.7

For women with minimal or mild disease (stage I/II), expert consensus is that the decision to surgically resect endometriotic lesions before other treatments should consider the patient’s age and ovarian reserve. In women with endometriomas receiving surgery for infertility or pain, excision of endometrioma capsule increases the rate of spontaneous postoperative pregnancy compared with drainage and electrocoagulation of the endometrioma wall. Surgery for endometriomas, however, can also reduce ovarian reserve and fertility due to removal of normal ovarian tissue, and a Cochrane review concluded that surgical treatment of endometriomas before assisted reproduction treatment (ART) has no benefit over expectant management regarding clinical pregnancy rate. For advanced endometriosis, expert consensus recommends IVF to reduce time to pregnancy, reserving surgery for women who present with larger or symptomatic endometriomas. Controlled ovarian stimulation for IVF does not increase recurrence of endometriosis. If endometriomas are surgically removed, this should be by cystectomy rather than fenestration/coagulation or laser ablation as this reduces symptom recurrence and improves pregnancy rates.7

Complications

The main complications of endometriosis include infertility or sub-fertility, chronic pain, and debilitating persistent symptoms including dysmenorrhoea, dyspareunia, and dyschezia. Endometriosis can lead to complications of surgical procedures, anatomical abnormalities due to possible adhesions, bowel or/and bladder dysfunction, and in the case of ovarian endometriomas to the development of cancer. Endometriosis negatively affects patients’ health-related quality-of-life, and the social, emotional, sexual well-being, daily routines, family planning, and productivity of the individual in the working environment. Bowel dysfunction like constipation or other digestive problems can appear in those who have endometriosis because of the inflammatory process of irritation of the gastrointestinal system. Patients with endometriosis report higher stress levels, poor quality of sleep, and lower levels of physical activity.2

Patients with endometriosis have reduced chances of childbearing, and a higher risk for miscarriage and ectopic pregnancies compared to women free of the disease. Recurrence rates of endometriosis after surgery varies between 6-to-67 per cent. Medical treatment can be effective, but in 5-to-59 per cent of patients the pain continues to exist at the end of therapy, and pain recurrence has been reported at 17-to-34 per cent.2

Prognosis

While currently there is no cure for endometriosis, in most cases, symptoms improve with the use of medications, surgery, or both. Researchers continue to investigate and find new reasons why endometriosis occurs, and what influences its severity. Research is underway to find medications that are specifically designed to target endometriotic tissue, while leaving healthy tissue unharmed.

These peptide medications work to fine-tune faulty molecular processes that lead to the growth of excess tissues. Scientists are also working to find medicines that may help treat endometriosis by altering or reducing levels of macrophages, and are also investigating if nano-medicine may be useful for treating and diagnosing endometriosis. Non-invasive therapies such as physical therapy are being tested to identify if they can reduce endometriosis symptoms. In a 2021 study, regular pelvic floor physiotherapy was found to reduce pain during intercourse, chronic pelvic pain, and improved pelvic relaxation in women with endometriosis.9

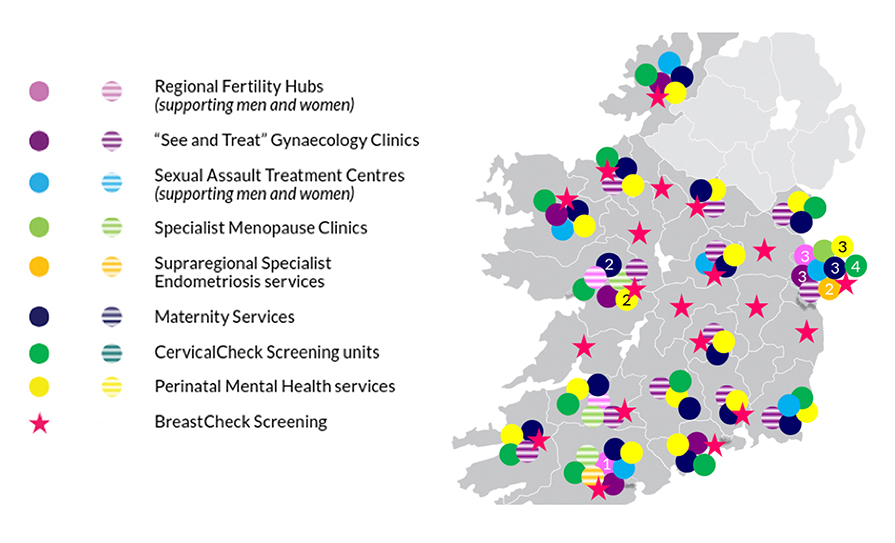

Researchers continue to look for ways to diagnose endometriosis earlier, improve treatment options, and ultimately reduce the risk of serious complications. Women’s health advocates also continue to call on the research community to fill serious knowledge gaps that make the diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis difficult. Patient education and raising awareness about the condition and its treatments can help support those experiencing the illness, and improve their quality-of-life. The EAI (www.endometriosis.ie) provides information and support for women with endometriosis in Ireland.

THERESA LOWRY-LEHNEN, RGN, GPN, RNP, BSc, MSc, M Ed, PhD, Clinical Nurse Specialist and Associate Lecturer, South East Technological University

References

- Hunt G, Allaire C, Yong P, Dunne C. (2021). Endometriosis: An update on diagnosis and medical management. BC Medical Journal. BCMJ, Vol 63, Issue 4, pp 158-163; May 2021

- Tsamantioti E, Mahdy H. (2022). Endometriosis. Stat Pearls Publishing; 2022 Jan. Available at: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ books/NBK567777/

- Malvezzi H, Marengo EB, Podgaec, S, et al. (2020). Endometriosis: Current challenges in modeling a multifactorial disease of unknown etiology. J Transl Med 18, 311. doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02471-0

- EAI (2022). Endometriosis. Endometriosis Association of Ireland. Available at: www.endometriosis.ie/about-endometriosis/

- ESHRE (2022). ESHRE Guideline Endometriosis. The European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology. Available at: www.eshre.eu/Guidelines-and-Legal/Guidelines/ Endometriosis-guideline.aspx

- Becker C, Bokor A, Heikinheimo O, Horne A, Jansen F, et al. (2022). ESHRE Endometriosis Guideline Group, ESHRE Guideline: Endometriosis. Human Reproduction Open, Vol 2022, Issue 2, 2022, hoac009. doi: 10.1093/ hropen/hoac009

- BMJ (2014). Endometriosis. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1752

- HSE (2021). Endometriosis. Available at: www2.hse.ie/ conditions/endometriosis/treatment/

- Medical News Today. (2021). The latest in endometriosis research: Ways forward. Available at: www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/ the-latest-in-endometriosis-research-ways-forward

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.