Bladder pain syndrome also known as interstitial cystitis, involves bladder pain or discomfort that can profoundly impact quality-of-life.

Bladder pain syndrome is challenging to diagnose, prevent, and treat because its basic science and pathophysiology are poorly understood. The prevalence of bladder pain syndrome varies widely and is estimated to be from 1-to-20 per cent. It is estimated that 90 per cent of people with interstitial cystitis are women.

The symptoms of bladder pain syndrome are discomfort with a frequent and often urgent need to pass urine. The findings of interstitial cystitis are suprapubic or retropubic pain, pressure, or discomfort related to the bladder. The pain usually increases with intensity during bladder filling and may persist or disappear after voiding.

To date, there is no curative treatment, and the primary goal of management is to provide symptom relief to achieve an adequate quality-of-life. There are many therapeutic approaches for bladder pain syndrome, none of which have been proven helpful for all patients.

Women with bladder pain syndrome also have other associated urinary symptoms and a higher prevalence of specific systemic diseases (eg, inf lammatory bowel disease).

People with interstitial cystitis may have many of the following symptoms:

- An urgent need to urinate, both in the daytime and at night.

- A frequent need to urinate as many as 20 times a day or more.

- Pressure, pain, and tenderness around the bladder, pelvis, and perineum may increase as the bladder fills and relieves bladder empties.

- The sensation that they can’t hold as much urine as before.

- Pain during sexual intercourse.

Risk factors

- Sex: Women are diagnosed with interstitial cystitis more often than men.

- Age: Most people with interstitial cystitis are diagnosed during their 30s or older.

- Chronic pain disorder: Interstitial cystitis may be associated with other chronic pain disorders, such as irritable bowel syndrome or fibromyalgia.

- Stimulatory foods/drinks: Spicy foods and caffeine.

Pathophysiology

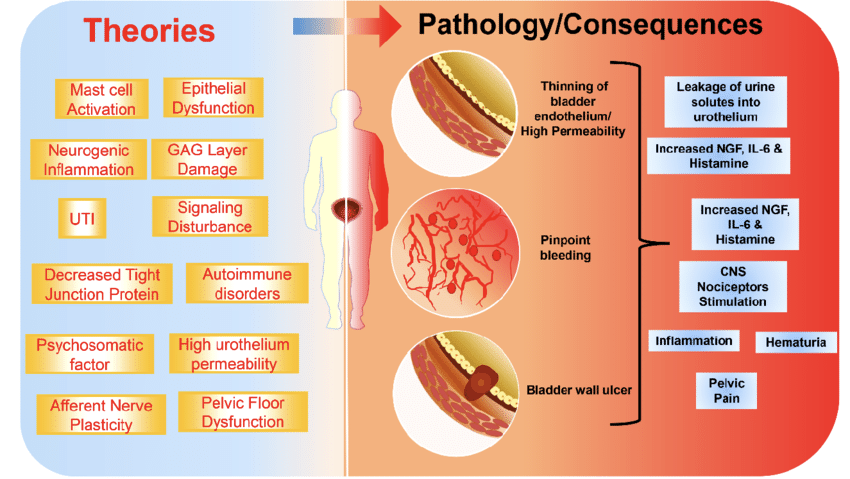

The pathophysiology of interstitial cystitis is complex and includes a number of different possible aetiologies. The main points are epithelial dysfunction, immune system activation (mast cells), neurogenic inf lammation, autoimmunity, and occult infection. One of the most common findings is the thinning of the bladder epithelium, suggesting injury and damage to the blood supply.

Other changes seen include increased histamine (produced due to the inf lammation process) and increased nerve cells in the bladder wall. An autoimmune response (when antibodies are made that act against a part of the body, such as in rheumatoid arthritis) may also be the cause in some people.

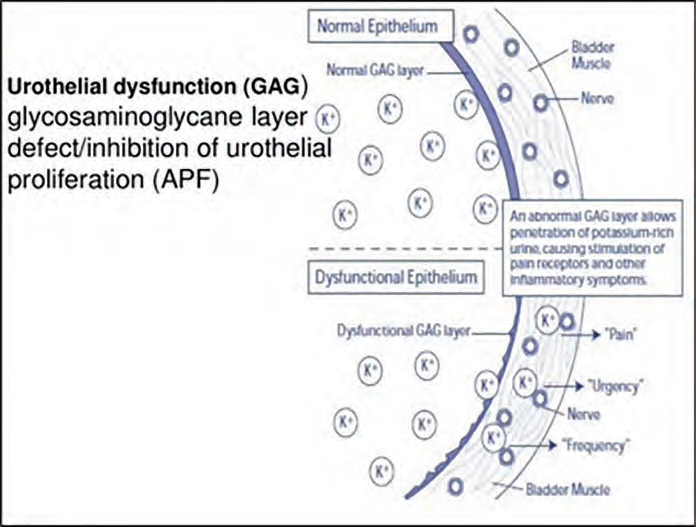

The urothelium, which is the inner surface of the urinary bladder, acts as a barrier between urine and the underlying bladder. The bladder mucus is a critical component of this function and is composed of glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), which are highly hydrophilic and trap water at the cell’s outer layer. The primary pathology of the disease is a disruption of the urothelial barrier, the penetration of the urinary solutes (potassium), causing injury to the nerves and muscles.

Evaluation

Clinical symptoms: This condition is suspected in patients who have pain in the urinary bladder for a few weeks. Specific findings include frequent urination to avoid discomfort, with bladder distension and pelvic tenderness on examination.

Physical examination: Tenderness or tightness of the pelvic floor muscles, which can be identified by palpation of the levator muscles on pelvic examination, is consistent with the diagnosis.

Findings on examination that require workup for other diagnoses include significant pelvic prolapse, urethral diverticulum, uterine/cervical mass, and eroded/exposed vaginal mesh.

Additional testing

Urine tests: Urinalysis and post void residual (PVR) urine volume.

Urinalysis with microscopy is performed to rule out infection and check for haematuria. A urine culture should be performed if urinalysis results suggest urinary tract infection. A PVR of urine can be measured by ultrasound

Cystoscopy: Cystoscopy is not a mandatory tool to make the diagnosis of interstitial cystitis. However, it may be performed to exclude other aetiologies either on initial presentation or in patients who do not respond to treatment with oral medications, and can help in the treatment. Over 50 per cent of patients may experience some symptom relief, but this will rarely last longer than six months. Cystoscopy can be used for cystodistension of the bladder and fulguration of Hunner’s ulcers/ lesions.

There are typical findings of lesions related to interstitial cystitis during cystoscopy:

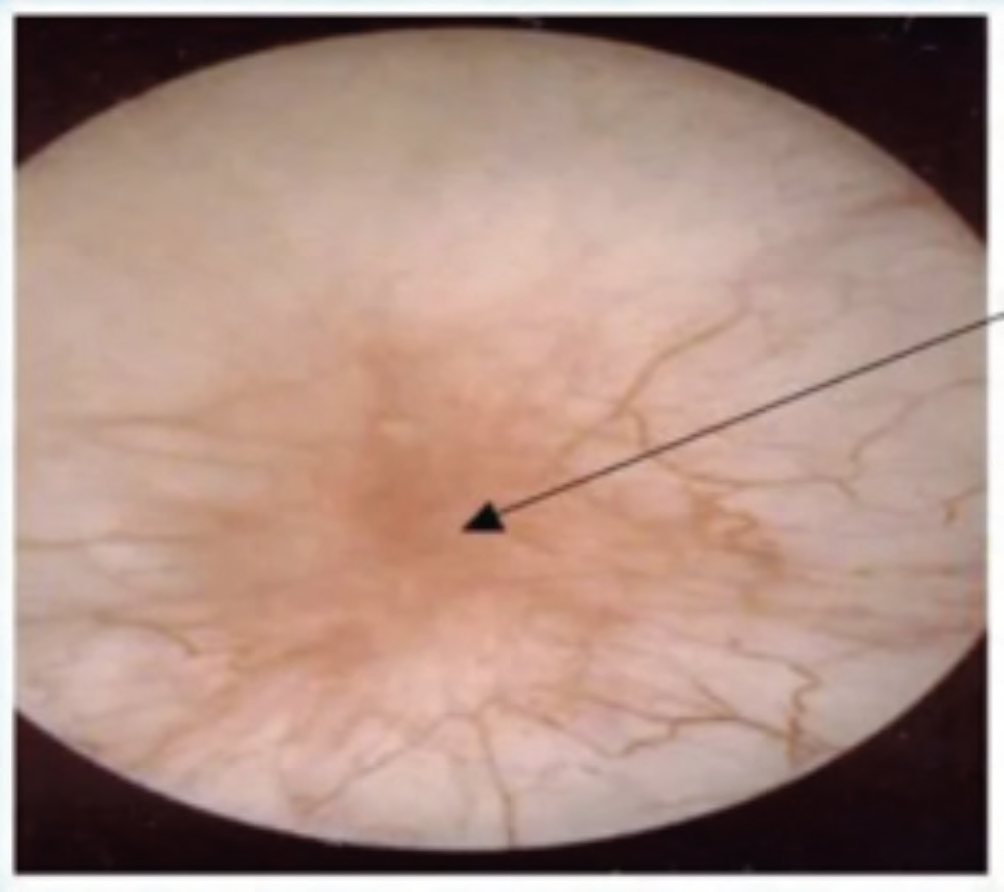

- Hunner’s lesions (reddened lesions on the bladder mucosa with attached fibrin deposits; typically bleed after hydrodistension) in 5-to-10 per cent of patients, and are highly specific. To identify Hunner’s lesions, cystoscopy is performed with direct visualisation before and after hydrodistension, and biopsies are taken of suspected lesions (see Image 1).

- Glomerulations (punctuate petechial haemorrhage), which appear after hydrodistension (see Image 2).

Both can be found in a patient with interstitial cystitis, but not all patients with interstitial cystitis will have them (not reliable criteria).

To date, there is no curative treatment, and the primary goal of management is to provide symptom relief to achieve an adequate quality-of-life

Histology

Increased numbers of mast cells on histologic examination of bladder biopsy specimens.

Biomarkers of interstitial cystitis

- GB-51.

- HB-EGF.

- APF (anti proliferative factor) is emerging as the best candidate for a biomarker for interstitial cystitis, but further studies and trials are needed. Excluding other aetiologies is essential.

Diagnosis

The American Urological Association (AUA) guidelines use the following definition of interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome: “An unpleasant sensation (pain, pressure, discomfort) perceived to be related to the urinary bladder, associated with lower urinary tract symptoms of more than six weeks duration, in the absence of infection or other identifiable causes.”

The clinical diagnosis requires a careful history, physical examination, and laboratory testing to document the disorder’s basic symptoms and exclude infections or other disorders.

Differential diagnosis

- Bladder or urethral cancer.

- Infections.

- Benign pelvic abnormalities.

- Intravesical pathology.

- Urethral diverticulum.

- Neurologic conditions.

- Chronic pelvic pain syndromes.

Treatment

There is no curative treatment for interstitial cystitis and the main goal is to manage symptomatic relief in order to achieve an adequate quality-of-life. Effective pain management is an essential component and may require a multidisciplinary, multimodal approach.

There are many therapeutic approaches, none of which have been proven helpful for all patients. The decision to start pharmacological treatment must be individualised after shared decision-making considering the severity of symptoms, the frequency of flares, patient preference, and the potential adverse effects of continued reliance on analgesic use.

Behavioural/non-pharmacologic treatments

- Patient education.

- Evaluate for comorbid conditions.

- Self-care and lifestyle modification – dietary modification: Avoid acidic foods, coffee, tea, soda, spicy foods, artificial sweetener, and alcohol.

- Pelvic floor myofascial physical therapy.

Pharmacological treatments

- Pain management agents (eg, urinary analgesics, paracetamol, NSAIDs, opioid/ non-opioid medications).

- Amitriptyline, cimetidine, pentosan polysulfate sodium (PPS), hydroxyzine.

- Antihistamines for patients with allergic disorders.

- Neuropathic pain agents.

Intravesical instillations

- Sodium hyaluronate (Cystistat), heparin, or lidocaine may be administered as intravesical treatments.

- Cystoscopy under anaesthesia with short-duration, low-pressure hydrodistension may be considered.

- If Hunner’s lesions are present, fulguration (with electrocautery) and injection of triamcinolone/Botox should be performed in a second-step procedure.

- Intra-detrusor botulinum toxin may be administered if other treatments have not provided adequate improvement in symptoms and quality-of-life.

Take home message about interstitial cystitis

- Interstitial cystitis is essentially an inflamed or irritated bladder wall.

- The cause of interstitial cystitis is unknown, and antibiotics are not the treatment.

- Symptoms include changes in urination such as frequency and urgency; pressure, pain, and tenderness around the bladder, pelvis, and the area between the anus and vagina or anus and scrotum; and pain during sex.

- There is no best way to diagnose interstitial cystitis.

- A variety of tests may be needed.

- Cystoscopy may be helpful for the diagnosis and treatment

- Treatments are aimed at easing symptoms.

- Lifestyle changes may be advised, and various medications and procedures are there.

PROF BARRY O’REILLY, Obstetrician/Gynaecologist, Sub specialist in Urogynaecology, Mater Private Hospital and University Hospital Cork; and DR YAIR DAYKAN, Urogynaecology Subspecialty Fellow, Cork University Hospital

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.