BPH is the most common cause of bladder outlet obstruction and lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) in men.

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is a term used to describe the non-malignant growth or hyperplasia of prostate tissue. The condition is characterised by an increase in epithelial and stromal cells in the peri-urethral area of the prostate. BPH is the most common cause of bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) and LUTS in men. It is extremely common and the prevalence of histological BPH at autopsy is as high as 90 per cent in men aged 81-90 years.1

The resultant effects of BPH on men are in the form of LUTS; the prevalence of which can range between 44 per cent in men between the ages of 40-59, and increasing to 70 per cent in males over 80 years of age.

LUTS can greatly affect the quality-of-life of these men, and due to the high prevalence of this condition in the community, can put pressure on both primary and secondary healthcare providers in both the investigation and management of this cohort of patients.

CASE REPORT

Mr Jones, a 62-year-old architect, presents to his GP complaining of new onset of urinary symptoms over the past three months. His main complaints are urinary frequency, nocturia (two-three times a night), a slow stream and more recently, difficulty in initiating his stream. He denies any visible haematuria or dysuria, and his urine dipstick is normal. He has no history of urinary tract infections (UTIs). His GP calculates his International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) score to be 15, indicating moderate voiding symptoms. Mr Jones says his lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) are impacting on his daily schedule, as he feels tired in work from getting up at night and is urinating more frequently during the day in work. He drinks six-to-seven cups of tea during the day and has a cup at night before going to bed. The GP performs a digital rectal exam (DRE), which reveals an enlarged but smooth-feeling prostate gland. Bloods are sent, including a U/E and PSA. The GP provides a frequency/ volume chart and advises Mr Jones to reduce his tea intake and switch to decaffeinated tea, and to limit his evening fluid intake.

At follow-up, his PSA is 0.75ng/ml, and his creatinine is normal at 73μmol/L. He reports some improvement in his frequency and nocturia following the previous lifestyle advice provided by the GP, however he now has the sensation of incomplete emptying. His frequency volume chart outrules nocturnal polyuria. He is started on an alpha1-blocker, to which he has great relief of his symptoms.

Two years later he re-presents to his GP with symptoms suggestive of a UTI. He is treated in the community and he is referred to a urologist who performs a flexible cystoscopy, which confirms an enlarged, moderately occlusive prostate gland. Uroflowometry shows a reduced urinary stream with a reduced maximum flow rate (QMax), a prolonged and intermittent stream, and post-void residual (PVR) of 185mls. His PSA is repeated and is now 1.6ng/ml and DRE again reveals a benign-feeling prostate gland. A 5-alpha reductase inhibitor (5-ARI) is added in combination with the alpha1-blocker. Repeat uroflowometry in six months shows an increased QMax and a PVR of just 50mls.

Primary care providers play an important role in the investigation and initial management of patients presenting with LUTS due to BPH. However, referral to a urologist is indicated in certain scenarios, including;

• Patients who present with acute urinary retention (AUR) or renal impairment due to BPH.

• Patients who fail to respond to or who are unable to tolerate the side-effects of medical therapy.

• Patients who present with visible or non-visible haematuria.

• Patients with signs or symptoms of high pressure chronic retention (tense, distended bladder, bedwetting, progressive renal failure).

Pathophysiology

Despite symptomatic BPH being first described from as early as 1649, the pathophysiology of this disease process remains relatively poorly understood. Interactions between the epithelium and the stroma are regulated by the androgen receptor and dihydrotestosterone (DHT).

Both of these cause prostatic tissue enlargement with the development of characteristic enlarging benign nodules. About 90 per cent of serum testosterone is converted to the more potent DHT by the enzyme 5-alpha reductase-2 in prostatic tissue. This is not the only pathway that promotes prostatic growth, which is the basis as to why not all patients with BPH respond to 5-ARIs.

DHT upregulates several growth factors in BPH such as fibroblast growth factor (FGF), epithelial growth factor (EGF), insulin-like growth factor (IGF), keratinocyte growth factor (KGF), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).

Paracrine cellular alterations that include proliferation, quiescence, and apoptosis all result in prostatic tissue expansion.

The pathophysiological basis of BOO resulting from BPH has been extensively studied; it can be a result of both dynamic and static components of BPH:

- Dynamic component: 1-adrenoreceptor mediated prostatic smooth muscle contraction. This effect is the rationale for α-adrenoreceptor blockade treatment.

- Static component: This is a result of the volume effect of prostatic tissue hyperplasia.

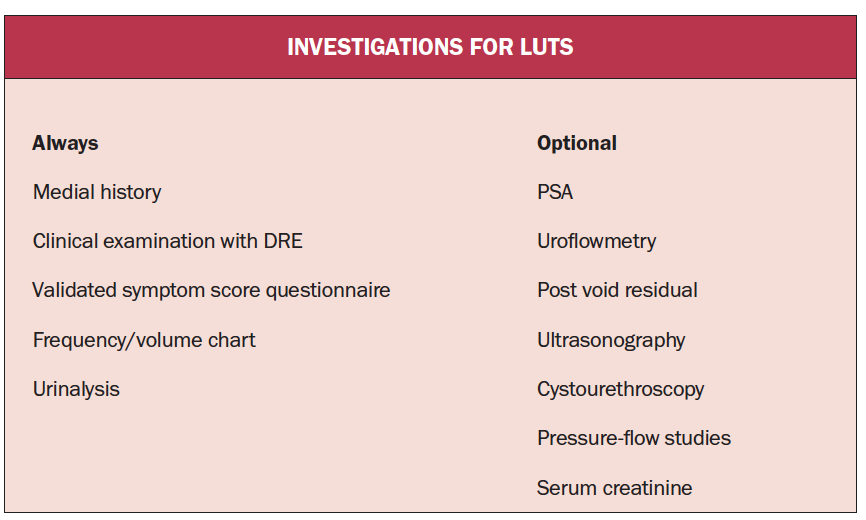

Investigations

All patients presenting with bothersome LUTS thought to be as a result of BPH should have a thorough clinical history taken and clinical examination performed. Symptom severity should be assessed using a validated assessment tool, with the IPSS being the most commonly used assessment tool. DRE should always be performed to rule out the presence of a prostate malignancy and to assess prostate size and shape. Laboratory investigations that should be performed include urinalysis, serum creatinine measurement, and prostate specific antigen (PSA) measurement. Other useful investigations for BPH can include uroflowometry and PVR measurement, renal ultrasonography, frequency/volume charts, and pressure flow studies.

Men should be counselled appropriately prior to PSA measurement. A PSA level >1.4ng/ml is a predictor of symptom progression in men with BPH. Patients with an elevated serum creatinine should be investigated with renal ultrasonography as this may be indicative of high pressure chronic urinary retention – there may be clues of this in the history if there is any history of bedwetting. The relationship between patients whom have an elevated serum creatinine and hydronephrosis on ultrasound is directly proportional: Creatinine <115mmol/l: 0.8 per cent, creatinine 115-130mmol/l: 9 percent, and creatinine >130mmol/l: 33 per cent.2

Management

Conservative management:

Despite a range of different treatment options being available to men with BPH-related LUTS, some men do not have symptoms significant enough to warrant treatment. Many men presenting to primary care reporting LUTS may simply be seeking reassurance that their symptoms do not raise suspicion of a significant prostate cancer. In many men reporting LUTS, simple lifestyle modification may be sufficient to alleviate their symptoms.

Avoiding bladder irritants in the diet such as caffeine and alcohol, restricting fluid intake in the evening time in men with nocturia, and encouraging men to double void in cases of incomplete emptying can have a significant impact on symptoms. Very few men who report mild LUTS progress to develop significant complications as a result.3 For every six men who present with LUTS; three-out-of-six will remain static, two will progress, and one will improve.

Medical therapy:

Medical treatment is an option for men with more severe LUTS, or in patients who have not responded to, or have progressed on conservative management. Adrenoreceptors which are located within the stroma and smooth muscle of the prostate gland and bladder neck control contractility.

Alpha-1-blockers target the dynamic component of symptomatic BPH, in which the smooth muscle contraction within the prostate inhibits emptying of the bladder. Alpha1-blockers that are currently available are doxazosin, terazosin, alfuzosin, tamsulosin, silodosin, and naftopidil.

In contrast, 5-ARIs target the static component of BPH, where the mass effect of the enlarged prostate gland prevents bladder emptying. The mechanism of action lies in the inhibition of the 5α-reductase enzyme, which leads to apoptosis of prostate epithelial cells, thus reducing prostate size and facilitating unobstructed bladder emptying.

The benefit of 5-ARIs in comparison with A1-blockers is that 5-ARIs reduce the risk of disease progression, with lower levels of AUR and a reduced need for surgical intervention seen in patients treated with 5-ARIs when compared with placebo.4 However, the time to clinical benefit in patients treated with 5-ARIs is only evident following at least six months of treatment, whereas symptomatic benefit is seen within days of starting treatment with A1-blockers.

Surgical treatment:

In recent years, novel therapies have been developed in the surgical treatment of BPH. The prostatic urethral lift or urolift is one such treatment which has gained popularity in recent years. This procedure involves the insertion of multiple suture-based implants into the prostate under cystoscopic guidance with the aim of relieving prostatic obstruction of the urethra and bladder. The benefit of urolift is significantly lower sexual side-effects when compared with transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP), however, symptomatic improvement is reported as less pronounced.5

Holmium enucleation of the prostate (HoLEP) and photoselective vaporisation of the prostate (PVP) offer comparable symptomatic relief and are more haemostatic in nature so can offer reduced rates of complications.6,7

TURP remains the primary standard treatment for surgical intervention of LUTS secondary to BPH, and has remained so for >80 years.8 TURP utilises electrocautery to unobstruct the urethral channel by internally coring out the prostate. It is recommended in patients with moderate-to-severe BPH-related LUTS and an enlarged prostate.9

TURP can be performed using monopolar or bipolar electrocautery systems. Each system has advantages and disadvantages, however, bipolar is becoming an increasingly popular choice in Ireland and appears to have lower rates of transurethral resection (TUR) syndrome – a potentially life-threatening complication related to fluid overload and dilutional hyponatraemia. This is due to the fact that saline irrigation is used as opposed to the glycine irrigation used in monopolar TURP. Patients undergoing TURP should be counselled that it is performed under general or spinal anaesthetic. It usually requires an inpatient stay of between three and five days, and a urethral catheter is necessary post-operatively for the first one-to-two days. A more detailed explanation of the procedure, the risks and benefits, and post-operative care is available on the British Association of Urological Surgery (BAUS) website.

Conclusion

Due to our ever-ageing population, and the prevalence of BPH in the community, there is an increasing burden on our healthcare system at both primary and secondary care levels in the investigation and management of this patient cohort. Prostatic growth is a seemingly unavoidable consequence of ageing. The ultimate goal of treatment in these men should always be about improving their quality-of-life and arresting the progression of disease.

By: DR KEN PATTERSON, Urology Registrar, Beaumont Hospital, Dublin; and MR NIALL DAVIS, Consultant Urologist and Senior Lecturer, Beaumont Hospital and the RCSI, Dublin

References

- Launer BM, McVary KT, Ricke WA, Lloyd GL. The rising worldwide impact of benign prostatic hyperplasia. BJU Int 2021;127:722-8

- Mebust WK, Holtgrewe HL, Cockett AT, Peters PC. Transurethral prostatectomy: Immediate and post-operative complications. A cooperative study of 13 participating institutions evaluating 3,885 patients. J Urol 1989;141:243-7

- Kirby RS. The natural history of benign prostatic hyperplasia: What have we learned in the last decade? Urology 2000;56:3-6

- McConnell JD, Bruskewitz R, Walsh P, et al. The effect of finasteride on the risk of acute urinary retention and the need for surgical treatment among men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Finasteride Long-term Efficacy and Safety Study Group. NEJM 1998;338:557-63

- Sønksen J, Barber NJ, Speakman MJ, et al. Prospective,

- randomised, multinational study of prostatic urethral lift versus transurethral resection of the prostate: 12-month results from the BPH6 study. Eur Urol 2015;68:643-52

- Skolarikos A, Papachristou C, Athanasiadis G, Chalikopoulos D, Deliveliotis C, Alivizatos G. Eighteen-month results of a randomised prospective study comparing transurethral photoselective vaporisation with transvesical open enucleation for prostatic adenomas greater than 80 cc. J Endourol 2008;22:2333-40

- Kuntz RM, Lehrich K, Ahyai SA. Holmium laser enucleation of the prostate versus open prostatectomy for prostates greater than 100 grams: Five-year follow-up results of a randomised clinical trial. Eur Urol 2008;53:160-6

- Cornu JN, Ahyai S, Bachmann A, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of functional outcomes and complications following transurethral procedures for lower urinary tract symptoms resulting from benign prostatic obstruction: An update. Eur Urol 2015;67:1066-96

- Gratzke C, Bachmann A, Descazeaud A, et al. EAU Guidelines on the assessment of non-neurogenic male lower urinary tract symptoms including benign prostatic obstruction. Eur Urol 2015;67:1099-109

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.